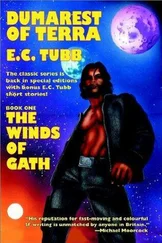

Herman Wouk - The Winds of War

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Herman Wouk - The Winds of War» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1971, Издательство: Collins, Жанр: Историческая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Winds of War

- Автор:

- Издательство:Collins

- Жанр:

- Год:1971

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Winds of War: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Winds of War»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

About the Author

Herman Wouk's acclaimed novels include the Pulitzer-Prize winning

;

;

;

;

;

; and

.

The Winds of War — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Winds of War», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The little knot of Americans stayed together, talking excitedly in low tense tones. Though the thing was no surprise, it felt strange now that it had happened; they stood on the soil of an enemy country. The debate among the correspondents, who kept glancing at policemen hovering nearby, was whether to go to their offices to clear out their desks, or head straight for the embassy. Several decided for the office first, arguing that once in the embassy they might be holed up for a long time, perhaps even until the diplomatic train left.

This put Aaron Jastrow in mind of his manuscript. He asked Father Spanelli to take them to the hotel before going on to the embassy. The priest was agreeable, and Natalie did not argue. She was in a shocked state. The baby was beginning to cry, and she thought of picking up some diapers and supplies for him. They returned to the car and drove to the Excelsior, but the priest suddenly braked, a block from the hotel; and he pointed through the windshield at two police cars pulled into the entrance driveway. Turning large, moist, worried brown eyes at Aaron Jastrow, he said, “Of course the manuscript is precious, Professore. Still, all things considered, had you not better go to your embassy first? If the worst comes to the worst, I can get your manuscript for you.”

“The embassy, the embassy,” Natalie said. “He’s right. The embassy.”

Jastrow nodded sadly.

But again, a couple of blocks from the embassy, Spanelli halted the car. A cordon of police and soldiers stood in front of the building. Across the street a small crowd of spectators stood waiting for some melodramatic occurrence. At the moment, from this distance, all looked quiet.

“Let us walk,” said the priest. “You should pass through that line with no trouble, but let us see.”

Natalie was sitting in back of the car. Jastrow turned to her and put a comforting hand over hers. His face was settling into a stony, weary, defiant expression. “Come, my dear. There’s not much choice now.”

They walked up the side of the street where the spectators were standing. On the edge of the crowd they encountered the Times man who had taken Natalie to the Japanese party. He was frightened and bitter; he urged them not to try to crash the cordon. The United Press correspondent had just attempted it, not five minutes earlier; he had been stopped at the gate, and after some argument a police car had appeared and had carried him off.

“But how can that be? That is not civilized, that is senseless,” exclaimed Father Spanelli. “We have many correspondents in the United States. It is idiotic behavior. It will be corrected.”

“When?” said the Times man. “And what will happen to Phil meantime? I’ve heard disagreeable things about your secret service.”

Holding her baby close, fighting off a feeling of sinking in black waters, a feeling like the worst of bad dreams, Natalie said, “What now, Aaron?”

“We must try to go through. What else is there?” He turned to the priest. “Or — Enrico, can we go to the Vatican now? Is there any point to that?”

The priest spread his hands. “No, no, not now. Don’t think of it. Nothing is arranged. It might be the worst of things to do. Given some time, something may be worked out. Surely not now.”

“Jesus Christ, there you are,” said a coarse American voice. “We’re all in big trouble, kids, and you’d better come with me.”

Natalie looked around into the worried, handsome, very Jewish face of Herbert Rose.

For a long while after that, the overpowering actuality was the smell of fish in the truck that was taking them to Naples, so strong that Natalie breathed in little gasps. The two drivers were Neapolitans whose business was bringing fresh fish to Rome. Rabinovitz had hired the truck to transport a replacement part for the ship’s old generator; a burnt-out armature had delayed the sailing.

Gray-faced with migraine, the stocky Palestinian now crouched swaying on the floor of the truck beside the burlap-wrapped armature, eyes closed, knees hugged in his arms. He had spent two days and nights hunting for the armature in Naples and Salerno, and then had tracked down a used one in Rome. He had brought Herbert Rose along to help him bargain for it. When Rose had first brought Jastrow and Natalie to the truck, parked on a side street near the embassy, the Palestinian had talked volubly, though he had since lapsed into this stupor; and the story he had then told had convinced Natalie to climb into the truck with her baby. After a few last agonized words with Father Spanelli about the manuscript, Aaron had followed her.

This was the Palestinian’s story. He had gone to the Excelsior at Herb Rose’s urging, to offer Jastrow and Natalie a last chance to join them. There in Aaron Jastrow’s suite he had found two Germans waiting. Well-dressed, well-spoken men, they had invited him inside and closed the door. When asked about Dr. Jastrow they had begun questioning him in a tough manner, without identifying themselves. Rabinovitz had backed out as soon as he could, and to his relief they had simply let him go.

During the first hour or so of the bouncing rattling ride in this dark, malodorous truck, Jastrow vainly talked over all the possible benign explanations for the presence of Germans in his hotel suite. It was almost a monologue, for Natalie was still dumb with alarm, Rabinovitz appeared sunk in pain, and Herbert Rose was bored. Obviously the men were Gestapo agents, Rose said, come to pick up the “blue chip,” and there was nothing more to discuss. But Dr. Jastrow was having second thoughts about this precipitate decision to go with Rabinovitz, and he was having them aloud. Finally, diffidently, he mentioned the diplomatic train as a possibility that still existed. This roused Natalie to say, “You can go back to Rome, Aaron, and try to get on that train. I won’t. Good luck.” Then Jastrow gave up, curled himself in a corner in his thick cape, and went to sleep.

The fish truck was not halted on the way to Naples. A familiar sight on the highway, it was a perfect cover for these enemy fugitives. When it reached the port city, night had fallen. As it slowly made its way through blacked-out streets toward the waterfront, policemen repeatedly challenged the drivers, but a word or two brought laughter and permission to go on. Natalie heard all this through a fog of tension and fatigue. The sense of everyday reality had quite left her. She was riding the whirlwind.

The truck stopped. A sharp rapping scared her, and one of the drivers said in hoarse Neapolitan accents, “Wake up, friends. We’re here.”

They descended from the truck to a wharf, where the sea breeze was an intensely sweet relief. In the cloudy night, the vessel alongside the wharf was a shadowy shape, where shadowy people walked back and forth. It appeared no larger to Natalie than a New York harbor sightseeing boat.

Dr. Jastrow said to Rabinovitz, “When will you sail? Immediately?”

With a grunt, Rabinovitz said, “No such luck. We must install this unit and test it. That’ll take time. Come aboard, and we’ll find a comfortable place for you.” He gestured at the narrow railed gangway.

“What’s the name of this boat?” Natalie asked.

“Oh, it has had many names. It’s old. Now it’s called the Redeemer. It’s Turkish registry, and once you’re aboard you will be secure. The harbor master and the Turkish consul here have an excellent understanding.”

Holding her baby close, Natalie said to Aaron Jastrow, “I’m beginning to feel like a Jew.”

He smiled sourly. “Oh? And I’ve never stopped feeling like one. I thought I’d gotten away from it. Obviously I haven’t. Come along, this is the way now.” Aaron set foot on the gangway first. She followed him, clutching her baby son in both arms, and Rabinovitz plodded up behind them. As Natalie set foot on the deck, the Palestinian touched her arm. In the gloom she could see him wearily smile. “Well, relax now, Mrs. Henry. You’re in Turkey. That’s a start.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Winds of War»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Winds of War» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Winds of War» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.