The white that rises from the bottom of her belly, and it feels like revolution itself, she thinks, with the terror and with toppling of marble statues and with chasing people out of their homes—only it is all inside her, while she stands, like this, on this stage, right now, naked more absolutely, more hopelessly, than even the armless Venus over by the door, and she wishes—

And she wishes that Julien did not leave, yesterday, the way he did. She told him to make a wish. He hid his face between her breasts. His shoulder jerked as shivers passed through his body. She waited, stroking his hair. She waited for his wish, but above that—for him to admit the obvious—how cold she was, how it had to mean she was the snow maiden, lying next to him. Then, she would say that she granted his wish. Who knows, maybe it would help him.

Instead, his shivers eased off and he said, “Ah, Constance. I am just a fool, aren’t I? A fool’s dream. The snow maiden doesn’t exist anywhere but on stage.”

Still unwitting, still blue and white, she pressed the back of her hand to his cheek and said, “Don’t you feel how cold I am? I am the snow maiden.”

He opened his eyes, pulling back to see her better. “Why do you say that? You’re not cold at all. You are very kind, and lovely, and you pity me, and I am thankful for that, but… you don’t know ice. You can’t speak for it.” He sat up on the ottoman and wiped his eyes.

She asked again, incredulous, “You don’t feel that I am cold?”

“What? No.”

Only then did she let her stunned mind consider what this could mean for her. Hope? She was a girl whose emotions made her cold—the stronger the emotion, the colder—and here was a boy who seemed not to notice it. She let herself be carried away for a few fleeting seconds, forgetting all these years, everything that happened between now and that anatomy theater over a decade ago. And just then, just that very second he heaved a sigh and said, “I know that is how I survived. I traded my leg for a fighting chance. But there are times when I just wish that I could feel the cold the way I used to. Like everybody else. With my fingers. My forehead. But I don’t. You can put ice to my skin, and I won’t know. I’m a cripple. The only cold I ever feel is the ice-trap on my missing leg. I don’t wish my leg back. I just… All I want is to be normal again.”

And this, these words and nothing else, suddenly made her red, so red that she jumped up and shouted, “Go away! Get the hell out!”

He scrambled up, repeating, What’s wrong with you? What did I do? He was reluctant to leave, and so she shouted, I don’t want you! and threw her powder and rouge boxes and stockings and gloves at him, until he collected his crutches and managed to clatter to the door and shut it behind himself.

* * *

It is this memory, today, now, on stage, that catches her breath, that makes her clench her hands and stare senselessly at the faces of her audience, at the walls, draperies, lanterns. There will be no miracle. It’s over. There is no point.

Marquis keeps pulling a cantabile out of his violin. Chairs creak. And creak. The weasel-man clicks his tongue.

“That’s it?” somebody mutters. She bows her head. She’ll leave now. She expects catcalls. She hears the chairs scratch the floor as the audience rises to its feet. Then the cantabile peters out. There is a strange movement in the air, half gasp, half breeze, and then she hears Marquis exclaim, “Behold the snow maiden!”

To her left, in the focal point of the other mirror, a ghostly shape is coalescing, a perfect silhouette of her, a reflection, a nude made in her image out of falling, swirling, sparkling snow. She barely gives it a glance, but she is relieved. She has done it, the miracle. Again. It snows. She is so tired. But she’s free to leave the stage now. Another show is over. Everything returns to its tracks.

They will applaud. Then Marquis will sell some papier-mâché flowers out of the tin bowl.

But on this, the twenty-ninth day of March 1814, she looks up and to the back of the room, and forgets she wanted to leave. Snow falls and falls, out of thin air and onto the floor. She stares. She can’t tell when the door cracked open, when he clanked in, but he is standing there now, crutches angling out like bony, flightless wings; he’s come back, and he is looking her in the eyes.

The snow falls thicker and thicker, it piles up, it fills in the silhouette within which it falls, and spreads around it like a shiny halo; and as the ghostly form solidifies, feet to waist to shoulders to head—as snowflakes turn to ice and ice becomes a maiden—Cherie feels red, and blue, and white, but mostly—something else.

It’s not an upset. She doesn’t need to give it a color. “Make a wish, Julien,” she whispers.

An excerpt from The Age of Ice

Please turn the page for a special preview of

The Age of Ice

By J. M. Sidorova

Available from Scribner July 2013

If you enjoy this excerpt, click here to download the full text.

Age of Ice

Currently available from Scribner

An Acclaim for The Age of Ice

“ The Age of Ice rekindles every far-flung childhood memory you have of what it means to experience a great book.”

—Téa Obreht,

New York Times bestselling author of

The Tiger’s Wife

“Everything you could want in a novel.”

—Karen Joy Fowler, author of

The Jane Austen Book Club and

We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves

“Ice binds the characters and shatters them apart, and the far reaches of the novel—Siberia, St. Petersburg, Paris, Herat, Calcutta, and New York over hundreds of years—are spanned as if by bridges of ice. Sidorova has created a tale at once familiar and foreign, thawed out of history and yet still fresh.”

—Paul Park, author of

A Princess of Roumania and

Ghosts Doing the Orange Dance

“I’m in awe. The Age of Ice is a luminous vision, a waking dream, utterly delicious. Sidorova is the best new writer I’ve come across in years.”

—Rudy Rucker, author of

The Ware Tetralogy

I was born of cold copulation, white-fleshed and waxy like a crust of fat on beef broth left outside in winter. I was born of seed that would have seized with frost if spilled on the newlyweds’ bed. I was born on the twenty-seventh of September because in the month of January my parents had been sealed in a wedding chamber made of ice.

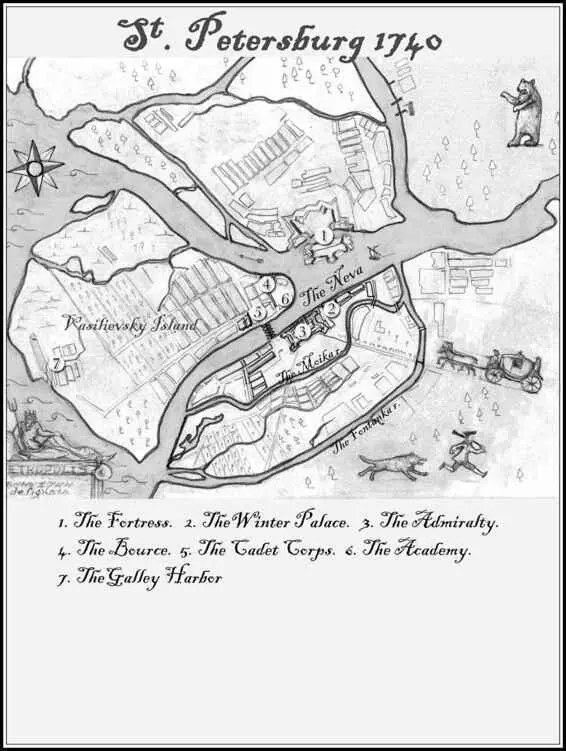

The year was 1740. The place—St. Petersburg, Russia. My country, corseted, wigged, and powdered on top but still darkly savage at heart, was panting and retching after the marathon Peter the Great had forced her to run. My would-be father, Prince Mikhail Velitzyn, scion of a family ancient and stately, had been transformed into a court jester. He had been forced to wear red-and-white-striped stockings and pretend to be a hen—to brood an imaginary clutch in Empress Anna Ioannovna’s menagerie of dwarfs, cripples, freaks, and victims. This was his punishment for an alleged affair with a Catholic noblewoman.

Читать дальше