“While I was looking out of the window, yes, sir.”

“Will you tell me all you did in the second story of the barn?”

“I think I told you all I did that I can remember.”

“Is there anything else?”

“I told you I took some pears up from the ground when I went up. I stopped under the pear tree and took some pears up. When I went up.”

“Have you now told me everything you did up in the second story of the barn?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I now call your attention and ask you to say whether all you have told me — I don’t suppose you stayed there any longer than necessary?”

“No, sir. Because it was close.”

“I suppose that was the hottest place there was on the premises.”

“I should think so.”

“Can you give me any explanation why all you have told me would occupy more than three minutes?”

“Yes, it would take me more than three minutes.”

“To look in that box — that you have described the size of — on the bench, and put down the curtain, and then get out as soon as you conveniently could — would you say you were occupied in that business twenty minutes?”

“I think so. Because I didn’t look at the box when I first went up.”

“What did you do?”

“I ate my pears.”

“Stood there eating pears, doing nothing?”

“I was looking out of the window.”

“Stood there looking out of the window, eating the pears.”

“I should think so.”

“How many did you eat?”

“Three, I think.”

“You were feeling better than you did in the morning?”

“Better than I did the night before.”

“That is not what I asked you. You were — then, when you were eating those three pears in that hot loft, looking out of that closed window — feeling better than you were in the morning? When you ate no breakfast?”

“I was feeling well enough to eat the pears.”

“Were you feeling better than you were in the morning?”

“I don’t think I felt very sick in the morning, only... yes, I don’t know but I did feel better. As I say, I don’t know whether I ate any breakfast or not. Or whether I ate a cookie.”

“ Were you then feeling better than you did in the morning?”

“I don’t know how to answer you, because I told you I felt better in the morning, anyway’.”

“Do you understand my question? My question is whether, when you were in the loft of that barn, you were feeling better than you were in the morning, when you got up?”

“No. I felt about the same.”

“Were you feeling better than you were when you told your mother you didn’t care for any dinner?”

“No, sir. I felt about the same.”

“Well enough to eat pears, but not well enough to eat anything for dinner.”

“She asked me if I wanted any meat.”

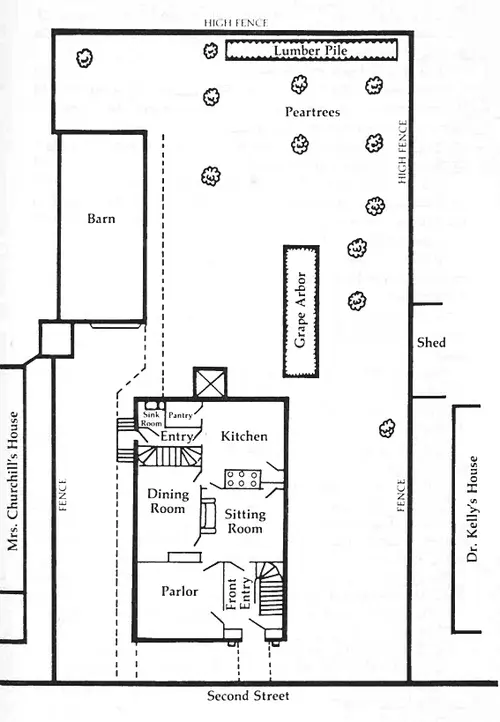

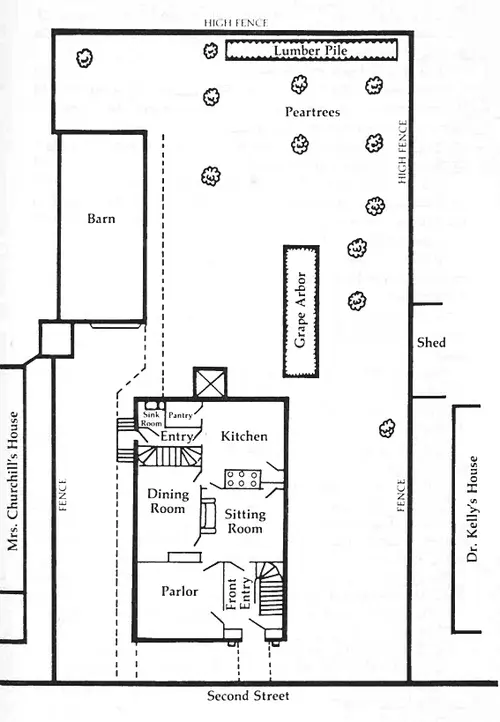

The answer hardly seemed responsive, but he decided not to pursue the matter of her comparative health any further. The eating of the pears, he reasoned — and, he thought, correctly so — was simply an attempt on her part to explain what had taken her so long up there in the barn. Her trip to the barn, of course, if she was lying, had been invented to place her at some distance from the house where the murders had taken place. If she had not been in the house at the time, she could not have committed the murders. But why choose the barn? Why not the front walk? Or a neighbor’s fence? Or indeed the shade of the pear tree? Knowlton walked back to his table, picked up a drawing of the house and yard, and carried it with him to the witness chair.

“I ask you, ” he said, “why you should select that place, which was the only place which would put you out of sight of the house, to eat those three pears in?”

“I cannot tell you any reason.”

“You observe that fact, do you not? You have put yourself in the only place, perhaps, where it would be impossible for you to see a person going into the house.”

“Yes, sir, I should have seen them from the front window.”

“From anywhere in the yard?”

“No, sir. Not unless from that end of the barn.”

“Ordinarily, in the yard, you could have seen them. And in the kitchen, where you’d been, you could have seen them.”

“I don’t think I understand.”

“When you were in the kitchen, you could see persons who came in at the back door.”

“Yes, sir.”

“When you were in the yard, unless you were around the corner of the house, you could see them come in at the back door.”

“No, sir. Not unless I was at the corner of the barn. The minute I turned, I could not.”

“What was there?”

“A little jog, like. The walk turns.”

“I ask you again to explain to me why you took those pears from the pear tree.”

“I didn’t take them from the pear tree.”

“From the ground, wherever you took them from, I thank you for correcting me. Going in the barn, going upstairs into the hottest place in the barn, in the rear of the barn, the hottest place, and there standing and eating those pears that morning.”

“I beg your pardon. I was not in the rear of the barn. I was in the other end of the barn that faced the street.”

“Where you could see anybody coming into the house?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Did you not tell me you could not?”

“Before I went into the barn. At the jog on the outside.”

“You now say... when you were eating the pears, you could see the back door?”

“Yes, sir.”

“So nobody could come in at that time without your seeing them.”

“I don’t see how they could.”

“After you got through eating your pears, you began your search.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then you did not see into the house.”

“No, sir. Because the bench is at the other end.”

“Now. I’ve asked you over and over again, and will continue the inquiry, whether anything you did at the bench would occupy more than three minutes.”

“Yes, I think it would. Because I pulled over quite a lot of boards in looking.”

“To get at the box?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Taking all that, what is the amount of time you think you occupied in looking for that piece of lead which you did not find?”

“Well... I should think perhaps I was ten minutes.”

“Looking over those old things.”

“Yes, sir. On the bench.”

“Now can you explain why you were ten minutes doing it?”

“No. Only that I can’t do anything in a minute.”

Except perhaps commit murder, Knowlton thought, and sighed heavily. She was watching him, a somewhat smug expression on her face now, as though her previous answer had been irrefutably logical. How could anyone be expected to do anything in a minute, least of all a woman intent on finding sinkers for a fishing trip she was to take on the Monday following the murders?

“When you came down from the barn,” he asked, “what did you do then?”

“Opened the sitting-room door, and went into the sitting room. Or pushed it open. It wasn’t latched.”

“What did you do then?”

“I found my father. And rushed to the foot of the stairs.”

“What were you going into the sitting room for?”

“To go upstairs.”

“What for?”

“To sit down.”

“What had become of the ironing?”

“The fire had gone out.”

Читать дальше