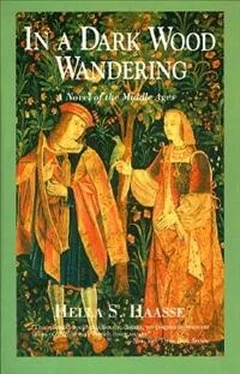

“This is the second time!” he said angrily; he jerked his mantle tightly around him and left the birth chamber without further ceremony.

Charles was soon to discover that King Louis was not a man who forgot quickly. The events in Blois seemed to have furnished the King with the pretence he had long sought to include Charles in the warnings and criticisms he directed to the feudal princes. He had been right in one respect: Charles had been stimulated by the birth of his son to renew his efforts to secure possession of Asti for his offspring. He applied with considerable reluctance to the King, who responded with obvious enjoyment that the thought of defending the interests of Orléans on the other side of the Alps was the farthest thing from his mind; he considered that he had the honor to be the friend of Sforza and not his enemy and he had no intention of fighting with him.

“Why not sell Asti to Sforza?” he asked at last, with raised brows. “You can always use the money, can’t you, worthy uncle?”

Charles declined this suggestion and left to return home. Not long afterward the King dictated a letter to Francesco Sforza in which he said, among other things: “The Duke of Orléans does not want to give up Asti. However, it seems to me that his health is failing. I am quite sure that Asti will be there for the taking as soon as he is dead — and then we will also own his son.”

Indeed, Charles was feeling far from well; for some time he had been suffering such violent attacks of gout that he could not walk without a cane. But it troubled him more that his right arm was stiff and painful: he found it impossible, after several fruitless attempts, to wield a pen. He was obliged to attach a seal to official documents to signal his approval, because he could no longer sign his name. From time to time his eyes refused to serve him; even with his strongest spectacles, bent forward over his book, he could make out nothing more than vague grey marks. He sought refuge with Marie, or in the nursery with his little daughter and his son — in that safe company he overcame his own fear of the blindness, the infirmity, which perhaps awaited him. As long as he was able, he wanted to act in his children’s interest; he reproached himself bitterly for having wasted so many years in pleasant tranquillity. For his son’s sake he had to enter into important relationships, to conclude alliances; to accomplish this he was prepared to go so far as to join the ranks of the rebel princes. He felt that he had no time to lose; death, or worse, the absolute helplessness of the living dead, could strike him suddenly and when he least expected it.

He sent messengers to Brittany; his nephew François Etampes had succeeded Richmont, who had died childless some years before. The young man promised his uncle to defend Asti by force of arms if necessary, to capture Milan and to stand by his young cousin of Orléans at all times. In addition, Charles ordered a marriage contract to be drawn up in great haste between his daughter Marie and his foster son Pierre, Bourbon’s youngest son. However, before he could make an equally satisfactory arrangement for his son and heir, envoys of the always well-informed King had arrived in Blois with a proposal that gave Charles a new headache: the King offered his daughter Jeanne as a bride for the heir of Orléans, in a manner which was more a command than a request. Charles, annoyed and upset, put off giving a definite answer from day to day in the hope that in the meantime the possibility of another arrangement would arise. And threats of serious disagreements between the King and the vassals of the Crown did in fact shove the matter of the marriage into the background for a while.

The princes, who had vainly attempted through petitions and personal visits, to effect the restoration of the honors which they believed were rightfully theirs, had finally realized what the King’s objectives were: he wanted their participation in the administration of the Kingdom to be reduced to a minimum; he did not want them at his court, nor did he want their advice in the Council — for that, he would choose his own people. The cities and territories which he had peremptorily confiscated from them upon his accession to the throne, would not be returned. He said repeatedly that he would not allow his regime to be poisoned by a group of men who were driven and impelled only by self-interest and ambition and who had always shown hostility to any confident, capable sovereign. Charles, through his negotiations for alliances with Bourbon and Brittany, was embroiled once more in the affairs of the feudal princes; he had to declare his solidarity with the struggle of that group in which, because of his birth and rank, he held so important a place.

He attended the protest meetings convened by Brittany; that Burgundy’s envoys appeared there at every turn did not please Charles. Their complaints and accusations far exceeded all the others in intensity: the King had occupied the cities along the Somme and, through men whom he had met in Flanders years ago, maintained relations with the rebellious commercial cities. Finally, the participants in the meetings decided to unite openly in a coalition “for the interests of the common welfare.” They would gather together to show that the King’s behavior was damaging to the landed interests and the honor of the Kingdom. But before they could proceed, the King summoned them — in a document which demonstrated how well-informed he was — to a meeting in Tours. The vassals of the Crown set out in a less than hopeful mood; they knew they could expect nothing good from a man who, for political reasons, had feigned friendship and familiarity with them for twenty years.

Charles came to Tours accompanied by Dunois; he was present at conferences presided over by the King himself. Coldly and sharply Louis put his case to them once more, arguing that the measures he had taken were necessary because of the confusion into which affairs of state had fallen during the last years of his father’s reign. In connection with the princes’ demands, he made a long speech full of generalities about obligations, about obedience and loyalty. Finally he said, looking at the rows of faces with a somewhat sour smile, that he would be sorry if the maintenance of his authority forced him to victimize anybody.

The lords heard these words in silence. They recognized his iron will and his implacable antipathy. They had no doubt that the sole purpose of this meeting was to impress upon them anew, before they pursued their reckless path, the threat of the King’s power. However, they remained resolute. Brittany, Bourbon, Anjou and, especially, Burgundy wanted nothing more than to take up arms openly against the man who had forthrighdy said that he intended once and for all to crush the political power of the nobility.

Charles d’Orléans sat huddled in his fur-lined mantle — these December days were bitter cold — among the peers of France. He felt extremely tired, and shivered now and then as though with fever. Cailleau had advised in the strongest terms against this journey to Tours; in such damp raw weather Monseigneur was usually half-crippled with gout. Moreover, his heart had been troubling him again for some time. But Charles refused to consider staying at home; he did not want to give the impression that he would shirk his obligations to his kinsmen and allies out of fear of the King.

In the meeting hall in Tours, he regretted his obstinacy; his heart throbbed so irregularly that he could scarcely breathe; his feet were ice cold; it cost him a great effort to sit upright and pay attention to the words of the speakers. Once he nearly dozed off; Dunois nudged him gently. He came to himself in time to hear the King express his lack of confidence in the good faith of François of Brittany who was on such a friendly footing with the envoys of England and Burgundy. Charles’ still-young nephew pressed his lips together in rage, but made no attempt to refute these accusations. When the meeting ended, he withdrew without saying a word. Charles, knowing that his sister’s son was deeply wounded, determined to see the King and attempt to cleanse his name of all suspicion. It was of great importance to Charles to bind the young man to him: Franc  is of Brittany could be a valuable friend for his son in the future. The King granted Charles a private audience.

is of Brittany could be a valuable friend for his son in the future. The King granted Charles a private audience.

Читать дальше

is of Brittany could be a valuable friend for his son in the future. The King granted Charles a private audience.

is of Brittany could be a valuable friend for his son in the future. The King granted Charles a private audience.