Milburg Mansfield - Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Milburg Mansfield - Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/43609

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The honour, power and profit derived by the noblesse in France all stopped with the Revolution. The National Assembly, however, refused to abolish titles. To do that body justice they saw full well that they could not take away that which did not exist as a tangible entity, and it is to their credit that they did not establish the new order of Knights of the Plough as they were petitioned to do. This would have been as fatal a step as can possibly be conceived, though for that matter a plough might just as well be a symbol of knighthood as a thistle, a jaratelle , a gold stick or a black rod.

In France a whole seigneurie was slave to the seigneur. Under feudal rule the clergy (not the humble abbés and curés , but the bishops and archbishops) were frequently themselves overlords. They, at any rate, enjoyed as high privileges as any in the land, and if the Revolution benefited the lower clergy it robbed the higher churchmen.

Just previous to the Revolution, the clergy had a revenue of one hundred and thirty million livres of which only forty-two million five hundred thousand livres accrued to the curés . The difference represents the loss to the “Seigneurs of the Church.”

With the Revolution the whole kingdom was in a blaze; famished mobs clamoured, if not always for bread, at least for an anticipated vengeance, and when they didn’t actually kill they robbed and burned. This accounts for the comparative infrequency of the feudal châteaux in France in anything but a ruined state. Sometimes it is but a square of wall that remains, sometimes a mere gateway, sometimes a donjon, and sometimes only a solitary tower. All these evidences are frequent enough in the provinces of the Pyrenees, from the more or less complete Châteaux of Foix and of Pau, to the ruins of Lourdes and Lourdat, and the more fragmentary remains of Ultrera, Ruscino and Coarraze.

The mediæval country house was a château; when it was protected by walls and moats it became a castle or château-fort; a distinction to be remarked.

The château of the middle ages was not only the successor of the Roman stronghold, but it was a villa or place of residence as well; when it was fortified it was a chastel .

A castle might be habitable, and a château might be a species of stronghold, and thus the mediæval country house might be either one thing or the other, but still the distinction will always be apparent if one will only go deeply enough into the history of any particular structure.

Light and air, which implies frequent windows, have always been desirable in all habitations of man, and only when the château bore the aspects of a fortification were window openings omitted. If it was an island castle, a moat-surrounded château, – as it frequently was in later Renaissance times, – windows and doors existed in profusion; but if it were a feudal fortress, such as one most frequently sees in the Pyrenees, openings at, or near, the ground-level were few and far between. Such windows as existed were mere narrow slits, like loop-holes, and the entrance doorway was really a fortified gate or port, frequently with a portcullis and sometimes with a pont-levis .

The origin of the word château ( castrum , castellum , castle) often served arbitrarily to designate a fortified habitation of a seigneur, or a citadel which protected a town. One must know something of their individual histories in order to place them correctly. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, châteaux in France multiplied almost to infinity, and became habitations in fact.

In reality the middle ages saw two classes of great châteaux go up almost side by side, the feudal château of the tenth to the fifteenth centuries, and the frankly residential country houses of the Renaissance period which came after.

For the real, true history of the feudal châteaux of France, one cannot do better than follow the hundred and fifty odd pages which Viollet-le-Duc devoted to the subject in his monumental “ Dictionnaire Raisonée d’Architecture .”

In the Midi, all the way from the Italian to the Spanish frontiers, are found the best examples of the feudal châteaux, mere ruins though they be in many cases. In the extreme north of Normandy, at Les Andelys, Arques and Falaise, at Pierrefonds and Coucy, these military châteaux stand prominent too, but mid-France, in the valley of the Loire, in Touraine especially, is the home of the great Renaissance country house.

The royal châteaux, the city dwellings and the country houses of the kings have perhaps the most interest for the traveller. Of this class are Chenonceaux and Amboise, Fontainebleau and St. Germain, and, within the scope of this book, the paternal château of Henri Quatre at Pau.

It is not alone, however, these royal residences that have the power to hold one’s attention. There are others as great, as beautiful and as replete with historic events. In this class are the châteaux at Foix, at Carcassonne, at Lourdes, at Coarraze and a dozen other points in the Pyrenees, whose architectural splendours are often neglected for the routine sightseeing sanctioned and demanded by the conventional tourists.

There are no vestiges of rural habitations in France erected by the kings of either of the first two races, though it is known that Chilperic and Clotaire II had residences at Chelles, Compiègne, Nogent, Villers-Cotterets, and Creil, north of Paris.

The pre-eminent builder of the great fortress châteaux of other days was Foulques Nerra, and his influence went wide and far. These establishments were useful and necessary, but they were hardly more than prison-like strongholds, quite bare of the luxuries which a later generation came to regard as necessities.

The refinements came in with Louis IX. The artisans and craftsmen became more and more ingenious and artistic, and the fine tastes and instincts of the French with respect to architecture soon came to find their equal expression in furnishings and fitments. Hard, high seats and beds, which looked as though they had been brought from Rome in Cæsar’s time, gave way to more comfortable chairs and canopied beds, carpets were laid down where rushes were strewn before, and walls were hung with cloths and draperies where grim stone and plaster had previously sent a chill down the backs of lords and ladies. Thus developed the life in French châteaux from one of simple security and defence, to one of luxurious ease and appointments.

The sole medium of communication between many of the French provinces, at least so far as the masses were concerned, was the local patois . All who did not speak it were foreigners, just as are English, Americans or Germans of to-day. The peoples of the Romance tongue stood in closer relation, perhaps, than other of the provincials of old, and the men of the Midi, whether they were Gascons from the valley of the Garonne, or Provençaux from the Bouches-du-Rhône were against the king and government as a common enemy.

The feudal lords were a gallant race on the whole; they didn’t spend all their time making war; they played boules and the jeu-de-paume , and held court at their château, where minstrels sang, and knights made verses for their lady loves, and men and women amused themselves much as country-house folk do to-day.

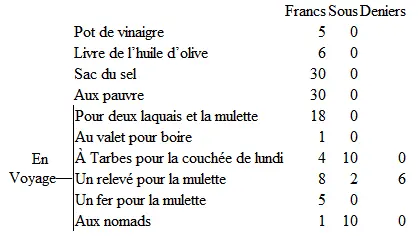

The following, extracted from the book of accounts of one of the minor noblesse of Béarn in the sixteenth century, is intimate and interesting. The master of this feudal household had a system of bookkeeping which modern chatelains might adopt with advantage. The items are curiously disposed.

Evidently “la mulette” was a very necessary adjunct and required quite as much as its master.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.