James Walsh - Psychotherapy

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Walsh - Psychotherapy» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_prose, psy_theraphy, foreign_edu, foreign_antique, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Psychotherapy

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Psychotherapy: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Psychotherapy»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Psychotherapy — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Psychotherapy», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

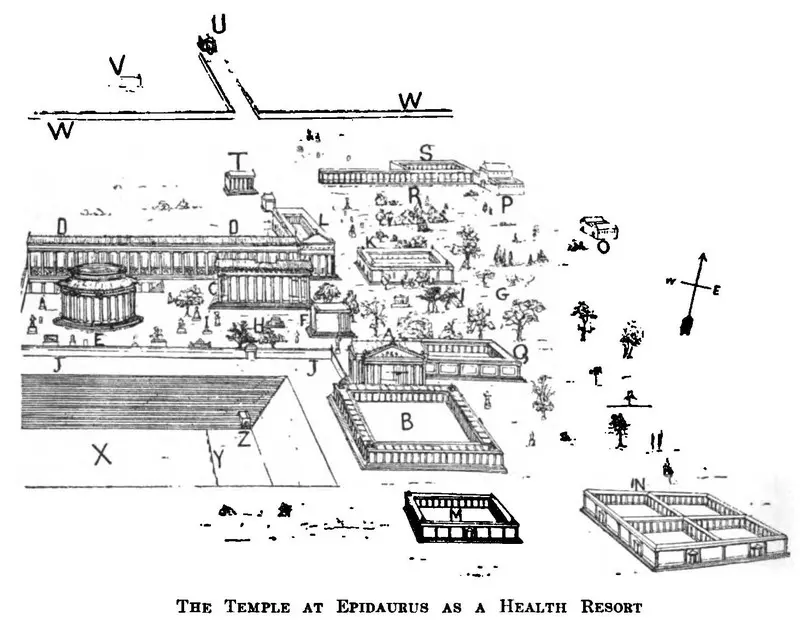

A, South Propylaea; B, Gymnasium; C, Temple of Esculapius; DD, East and West Abatons (temple enclosures); E, Pholos; F, Temple of Artemis; G, Grove; H, Small Altar; I, Large Alter; J, South Boundary; K, Square (building); L, Baths of Esculapius; M, Gymnasium and Hostel; N, Four Quadrangles (for promenade and exercise); O, Roman Building; P, Roman Bath; Q, Portico of Cotys; R, Northeastern Colonnade; S, Northeastern Quadrangle; T, Temple of Aphrodite (?); U, Northern Propylaea, on the Road to Epidaurus; V, Roman Building; W, Northern Boundary; X, Stadium; Y, Goal or Starting Line; Z, Tunnel between Temple and Stadium. (Caton.)

There are other phases of Egyptian medicine which serve to show us how early many of the psychological ideas that we now are trying to adopt and adapt in medicine had come to the thinkers in medicine of long ago. There is, for instance, now in the Berlin museum an interesting papyrus of the Middle Kingdom, the date of which is about 2500 B. C, in which there are many modern ideas. It is a dialogue which attempts the justification of suicide. The principal speaker, a man weary of life, has made up his mind to suicide, but is hesitant. The others who speak in the dialogue are his secondary personalities . The Egyptians considered that there were several of these interior persons with whom the man himself might have communication. A man could play draughts with his ba somewhat as we play solitaire. He could talk to and exchange gifts with his ka . He could argue and remain at variance, but more often come to an agreement, with his khou . This last was his luminous immortal ego , which, according to the then generally received Egyptian conception, formed a complete and independent personality. The whole scene thus outlined is typically modern in certain phases of its psychology, and presents the only known treatment for the tendency to suicide. While we have but this instance, there seems no doubt that the same system of persuasion must have been employed for the cure of other mental conditions than that which predisposes to suicide.

What is described in our quotation from Pinel as the most ancient form of psychotherapy has all down the centuries been the rule of life for patients at institutions similar to those of Egypt. We know more of Greece than of other countries; there the shrines of AEsculapius were in many ways what we now call sanatoria. They were spacious buildings pleasantly situated, the hours of rising and of rest were definitely regulated, the patients' minds were occupied with the details of the cure, they met pleasant companions from distant places, they had all the advantages of diversion of mind, simple diet, long hours in the open air and abundance of rest away from the ordinary worries of life. Besides, there had usually been some weeks or months of preparation during a lengthy journey and all the diversion of mind which that implies. No wonder that these institutions acquired a reputation for cures of symptoms which the physician had been unable to accomplish while the patient was at home in the midst of his daily cares and worries of life.

The temples in Egypt, in Assyria, in Greece, were much like the health institutions—"cure houses," as the expressive German phrase calls them—of our day. Pictures of the temple of AEsculapius at Epidaurus show a magnificent building with beautiful grounds, ample bathing facilities, and evidently many opportunities for a quiet, easy life far from the worries and bustle of the world and with everything that would suggest to the patient that he must get well. This phase of psychotherapy in the olden time is not only interesting in itself, but furnishes a valuable commentary on corresponding modern institutions, since it shows that it is not so much the physical influences, which have differed markedly at different periods, as the mental attitude so constantly influenced at these institutions which was the real therapeutic factor.

Now our sanatoria are nearly all founded on some special principle of therapeutics. Some of them have dietetic fads and no food out of which the life has been cooked is eaten. Some of them are absolutely vegetarian. Some of them depend on wonderful springs in their neighborhoods, others on certain forms of exercise, still others give the rest cure. All succeed in relieving many symptoms. No one who has analyzed the cures effected will think for a moment that it is the special therapeutic fad of the institution that accomplishes all the good done for patients suffering from so many different complaints. Similar ills often are affected quite differently, and, while some are relieved, others are not. Those who fail to be cured at one will, however, often be relieved at another. It depends on how much influence of mind is secured over the patient and how much diversion from thoughts of self is provided.

MIND HEALING IN GREECE

When Greece awoke to the great literary and scientific discussion of human thought that gave us such philosophic and scientific thinkers as Hippocrates, Plato and Aristotle, then psychotherapy, in the formal sense of caring for the mind of the patient as well as for his body, came to be explicitly recognized as having therapeutic value. Hippocrates insisted that medicine was an art rather than a science, that personality had much to do with it, and that the patient must be optimistically influenced in every way. The first of his aphorisms is well known, but few realize all of its significance. Hippocrates declares that "life is short and art long, the occasion fleeting, experience fallacious and judgment difficult. The physician must not only be prepared to do what is right himself, but also to make the patient, the attendants and externals coöperate." No one emphasized more than he the necessity for differentiating the individual patient, and to him we owe, in foundation at least, the aphorism that it is more important to know what sort of an individual has a disease than what sort of a disease the individual has, for the chances of cure greatly depend on favorable individuality.

Perhaps Hippocrates' most striking direct contribution to psychotherapy is his aphorism with regard to pain. He said: "Of two pains occurring together in different parts of the body, the stronger weakens the other." When the attention is distracted from pain, then it is lessened. Of two pains, then, only the one that attracts the most attention is much felt, and, if a slight pain is succeeded by a severe pain in another part of the body, the lesser pain will apparently become trivial, or, indeed, not be felt at all.

In Plato we find the direct philosophic expression of the value of psychotherapy. There had been during the preceding century a great increase in information with regard to the facts of physical nature, and especially the sciences relating to the human body, and so men had come, as they are prone to at such eras—our own, for instance—to think too much of the body and too little of the mind that rules it. Accordingly, we have from Plato a deliberate, emphatic assertion of this great truth under circumstances which make us realize how keenly he appreciated its significance for the art of medicine and for humanity.

Professor Osier, in his address, "Physic and Physicians as Depicted in Plato," 1 1 "AEquanimitas and Other Addresses."

tells a story which shows clearly how much the great Greek philosopher appreciated the place of psychotherapy.

Charmides had been complaining of a headache, and Critias had asked Socrates to make believe that he could cure him of it. Socrates said that he had a charm which he had learnt, when serving with the army, of one of the physicians of the Thracian king. Zamolxis. This physician had told Socrates that the cure of a part should not be attempted without treatment of the whole, and, also, that no attempt should be made to cure the body without the soul, "and, therefore, if the head and body are to be well, you must begin by curing the mind; that is the first thing. And he who taught me the cure and the charm added a special direction. 'Let no one,' he said, 'persuade you to cure the head until he has first given you his soul to be cured. For this,' he said, 'is the great error of our day in the treatment of the human body, that physicians separate the soul from the body. '"

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Psychotherapy»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Psychotherapy» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Psychotherapy» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.