James Walsh - The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Walsh - The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_prose, История, foreign_edu, foreign_antique, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

John Ruskin once said that a proper estimation of the accomplishments of a period in human history can only be obtained by careful study of three books—The Book of the Deeds, The Book of the Arts, and the Book of the Words, of the given epoch. The Thirteenth Century may be promptly ready for this judgment of what it accomplished for men, of what it wrote for subsequent generations, and of the artistic qualities to be found in its art remains. In the Book of the Deeds of the century what is especially important is what was accomplished for men, that is, what the period did for the education of the people, not alone the classes but the masses, and what a precious heritage of liberty and of social coordination it left behind. To most people it will appear at once that if the most important chapter of Thirteenth Century accomplishment is to be found in the Book of its Deeds and the deeds are to be judged according to the standard just given of education and liberty, then there will be no need to seek further, since these are words for which it is supposed that there is no actual equivalent in human life and history for at least several centuries after the close of the Thirteenth.

As a matter of fact, however, it is in this very chapter that the Thirteenth Century will be found strongest in its claim to true greatness. The Thirteenth Century saw the foundation of the universities and their gradual development into the institutions of learning which we have at the present time. Those scholars of the Thirteenth Century recognized that, for its own development and for practical purposes, the human intellect can best be trained along certain lines. For its preliminary training, it seemed to them to need what has since come to be called the liberal arts, that is, a knowledge of certain languages and of logic, as well as a thorough consideration of the great problems of the relation of man to his Creator, to his fellow-men, and to the universe around him. Grammar, a much wider subject than we now include under the term, and philosophy constituted the undergraduate studies of the universities of the Thirteenth Century. For the practical purposes of life, a division of post-graduate study had to be made so as to suit the life design of each individual, and accordingly the faculties of theology, for the training of divines; of medicine, for the training of physicians; and of law, for the training of advocates, came into existence.

We shall consider this subject in more detail in a subsequent chapter, but it will be clear at once that the university, as organized by these wise generations of the Thirteenth Century, has come down unchanged to us in the modern time. We still have practically the same methods of preliminary training and the same division of post-graduate studies. We specialize to a greater degree than they did, but it must not be forgotten that specialism was not unknown by any means in the Thirteenth Century, though there were fewer opportunities for its practical application to the things of life. If this century had done nothing else but create the instrument by which the human mind has ever since been trained, it must be considered as deserving a place of the very highest rank in the periods of human history.

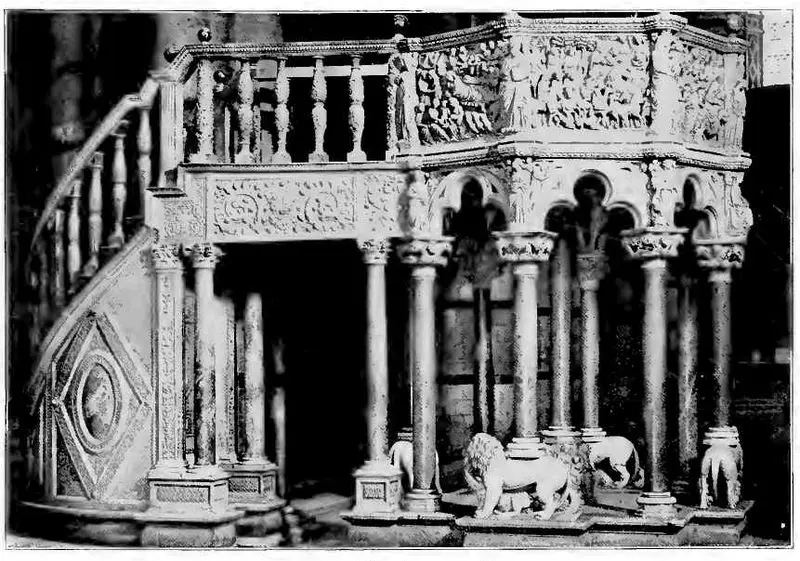

It is, however, much more for what it accomplished for the education of the masses than for the institutions it succeeded in developing for the training of the classes, that the Thirteenth Century merits a place in the roll of fame. This declaration will doubtless seem utterly paradoxical to the ordinary reader of history. We are very prone to consider that it is only in our time that anything like popular education has come into existence. As a matter of fact, however, the education afforded to the people in the little towns of the Middle Ages, represents an ideal of educational uplift for the masses such as has never been even distantly approached in succeeding centuries. The Thirteenth Century developed the greatest set of technical schools that the world has ever known. The technical school is supposed to be a creation of the last half century at the outside. These medieval towns, however, during the course of the building of their cathedrals, of their public buildings and various magnificent edifices of royalty and for the nobility, succeeded in accomplishing such artistic results that the world has ever since held them in admiration, and that this admiration has increased rather than diminished with the development of taste in very recent years.

Nearly every one of the most important towns of England during the Thirteenth Century was erecting a cathedral. Altogether some twenty cathedrals remain as the subject of loving veneration and of frequent visitation for the modern generation. There was intense rivalry between these various towns. Each tried to surpass the other in the grandeur of its cathedral and auxiliary buildings. Instead of lending workmen to one another there was a civic pride in accomplishing for one's native town whatever was best.

PULPIT (PISANO, SIENA)

Each of these towns, then, none of which had more than twenty thousand inhabitants except London, and even that scarcely more, had to develop its own artist-artisans for itself. That they succeeded in doing so demonstrates a great educational influence at work in arts and crafts in each of these towns. We scarcely succeed in obtaining such trained workmen in proportionately much fewer numbers even with the aid of our technical schools, and while these Thirteenth Century people did not think of such a term, it is evident that they had the reality and that they were able to develop artistic handicraftsmen—the best the world has ever known.

With all this of education abroad in the lands, it is not surprising that great results should have flowed from human efforts and that these should prove enduring even down to our own time. Accomplishments of the highest significance were necessarily bound up with opportunities for self-expression, so tempting and so complete, as those provided for the generations of the Thirteenth Century. The books of the Words as well as of the Arts of the Thirteenth Century will be found eminently interesting, and no period has ever furnished so many examples of wondrous initiative, followed almost immediately by just as marvelous progress and eventual approach to as near perfection as it is perhaps possible to come in things human. Ordinarily literary origins are not known with sufficient certainty as to dates for any but the professional scholar to realize the scope of the century's literature. Only a very little consideration, however, is needed to demonstrate how thoroughly representative of what is most enduring in literary expression in modern times, are the works in every country that had origin in this century.

There was not a single country in civilized Europe which did not contribute its quota and that of great significance to the literary movement of the time. In Spain there came the Cid and certain accompanying products of ballad poetry which form the basis of the national literature and are still read not only by scholars and amateurs, but even by the people generally, because of the supreme human interest in them. In England, the beginning of the Thirteenth Century saw the putting into shape of the Arthur Legends in the form in which they were to appeal most nearly to subsequent generations. Walter Map's work in these was, as we shall see, one of the great literary accomplishments of all time. Subsequent treatments of the same subject are only slight modifications of the theme which he elaborated, and Mallory's and Spenser's and even our own Tennyson's work derive their interest from the humanly sympathetic story, written so close to the heart of nature in the Thirteenth Century that it will always prove attractive.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.