James Walsh - The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Walsh - The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_prose, История, foreign_edu, foreign_antique, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Reinach, in his Story of Art Throughout the Ages, 10 10 Scribners, New York, 1905.

has been so enthusiastic in this matter that a paragraph of his opinion must find a place here. Reinach, it may be said, is an excellent authority, a member of the Institute of France, who has made special studies in comparative architecture, and has written works that carry more weight than almost any others of our generation:

"If the aim of architecture, considered as an art, should be to free itself as much as possible from subjection to its materials, it may be said that no buildings have more successfully realized this ideal than the Gothic churches. And there is more to be said in this connection. Its light and airy system of construction, the freedom and slenderness of its supporting skeleton, afford, as it were, a presage of an art that began to develop in the Nineteenth Century, that of metallic architecture. With the help of metal, and of cement reinforced by metal bars, the moderns might equal the most daring feats of the Gothic architects. It would even be easy for them to surpass them, without endangering the solidity of the structure, as did the audacities of Gothic art. In the conflicts that obtain between the two elements of construction, solidity and open space, everything seems to show that the principle of free spaces will prevail, that the palaces and houses of the future will be flooded with air and light, that the formula popularized by Gothic architecture has a great future before it, and that following the revival of the Graeco-Roman style from the Sixteenth Century, to our own day, we shall see a yet more enduring renaissance of the Gothic style applied to novel materials."

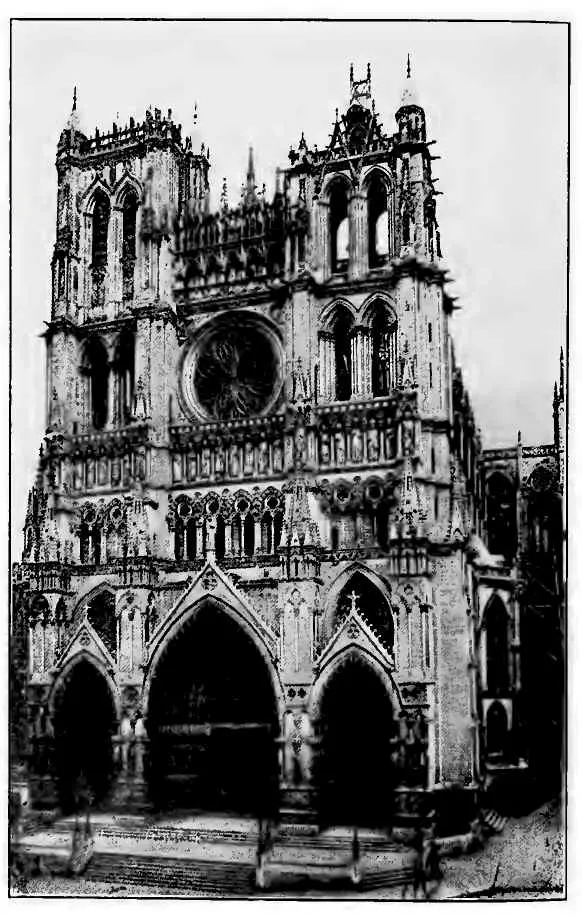

It would be a mistake, however, to think that the Gothic Cathedrals were impressive only because of their grandeur and immense size. It would be still more a mistake to consider them only as examples of a great development in architecture. They are much more than this; they are the compendious expression of the art impulses of a glorious century. Every single detail of the Gothic Cathedrals is not only worthy of study but deserving of admiration, if not for itself, then always for the inadequate means by which it was secured, and most of these details have been found worthy of imitation by subsequent generations. It is only by considering the separate details of the art work of these Cathedrals that the full lesson of what these wonderful people accomplished can be learned. There have been many centuries since, in which they would be entirely unappreciated. Fortunately, our own time has come back to a recognition of the greatness of the art impulse that was at work, perfecting even what might be considered trivial portions of the cathedrals, and the brightest hope for the future of our own accomplishment is founded on this belated appreciation of old-time work.

It has been said that the medieval workman was a lively symbol of the Creator Himself, in the way in which he did his work. It mattered not how obscure the portion of the cathedral at which he was set, he decorated it as beautifully as he knew how, without a thought that his work would be appreciated only by the very few that might see it. Trivial details were finished with the perfection of important parts. Microscopic studies in recent years have revealed beautiful designs on pollen grains and diatoms which are far beneath the possibilities of human vision, and have only been discovered by lens combinations of very high powers of the compound microscope. Always these beauties have been there though hidden away from any eye. It was as if the Creator's hand could not touch anything without leaving it beautiful as well as useful.

CATHEDRAL (AMIENS)

To as great extent as it is possible perhaps for man to secure such a desideratum, the Thirteenth Century workman succeeded in this same purpose. It is for this reason more than even for the magnificent grandeur of the design and the skilful execution with inadequate means, that makes the Gothic Cathedral such a source of admiration and wonder.

To take first the example of sculpture. It is usually considered that the Thirteenth Century represented a time entirely too early in the history of plastic art for there to have been any fine examples of the sculptor's chisel left us from it. Any such impression, however, will soon be corrected if one but examines carefully the specimens of this form of art in certain Cathedrals. As we have said, probably no more charmingly dignified presentation of the human form divine in stone has ever been made than the figure of Christ above the main door of the cathedral of Amiens, which the Amiennois so lovingly call their "beautiful God." There are some other examples of statuary in the same cathedral that are wonderful specimens of the sculptor's art, lending itself for decorative purposes to architecture. This is true for a number of the Cathedrals. The statues in themselves are not so beautiful, but as portions of a definite piece of structural work such as a doorway or a facade, they are wonderful models of how all the different arts became subservient to the general effect to be produced. It was at Rheims, however, that sculpture reached its acme of accomplishment, and architects have been always unstinted in their praise of this feature of what may be called the Capitol church of France.

Those who have any doubts as to the place of Gothic art itself in art history and who need an authority always to bolster up the opinion that they may hold, will find ample support in the enthusiastic opinion of an authority whom we have quoted already. The most interesting and significant feature of his ardent expression of enthusiasm is his comparison of Romanesque with Gothic art in this respect. The amount of ground covered from one artistic mode to the other is greater than any other advance in art that has ever been made. After all, the real value of the work of the period must be judged, rather by the amount of progress that has been made than by the stage of advance actually reached, since it is development rather than accomplishment that counts in the evolution of the race. On the other hand it will be found that Reinach's opinion of the actual attainments of Gothic art are far beyond anything that used to be thought on the subject a half century ago, and much higher than any but a few of the modern art critics hold in the matter. He says:

"In contrast to this Romanesque art, as yet in bondage to convention, ignorant or disdainful of nature, the mature Gothic art of the Thirteenth Century appeared as a brilliant revival or realism. The great sculptors who adorned the Cathedrals of Paris, Amiens, Rheims, and Chartres with their works, were realists in the highest sense of the word. They sought in Nature not only their knowledge of human forms, and of the draperies that cover them, but also that of the principles of decoration. Save in the gargoyles of cathedrals and in certain minor sculptures, we no longer find in the Thirteenth Century those unreal figures of animals, nor those ornaments, complicated as nightmares, which load the capitals of Romanesque churches; the flora of the country, studied with loving attention, is the sole, or almost the sole source from which decorators take their motives. It is in this charming profusion of flowers and foliage that the genius of Gothic architecture is most freely displayed. One of the most admirable of its creations is the famous Capital of the Vintage in Notre Dame at Rheims, carved about the year 1250. Since the first century of the Roman Empire art had never imitated Nature so perfectly, nor has it ever since done so with a like grace and sentiment."

Reinach defends Gothic Art from another and more serious objection which is constantly urged against it by those who know only certain examples of it, but have not had the advantage of the wide study of the whole field of artistic endeavor in the Thirteenth Century, which this distinguished member of the Institute of France has succeeded in obtaining. It is curious what unfounded opinions have come to be prevalent in art circles because, only too often, writers with regard to the Cathedrals have spent their time mainly in the large cities, or along the principal arteries of travel, and have not realized that some of the smaller towns contained work better fitted to illustrate Gothic Art principles than those on which they depended for their information. If only particular phases of the art of any one time, no matter how important, were to be considered in forming a judgment of it, that judgment would almost surely be unfavorable in many ways because of the lack of completeness of view. This is what has happened unfortunately with regard to Gothic art, but a better spirit is coming in this matter, with the more careful study of periods of art and the return of reverence for the grand old Middle Ages.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.