John George Wood - Common Objects of the Microscope

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John George Wood - Common Objects of the Microscope» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_prose, foreign_antique, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Common Objects of the Microscope

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Common Objects of the Microscope: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Common Objects of the Microscope»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Common Objects of the Microscope — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Common Objects of the Microscope», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

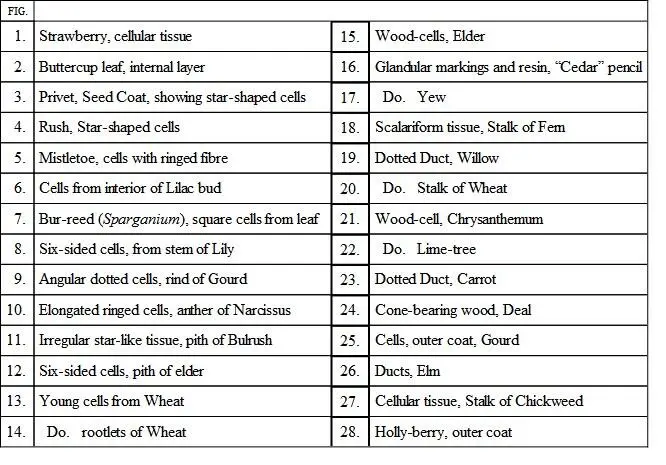

Vegetable Cells and their Structure—Stellate Tissues—Secondary Deposit—Ducts and Vessels—Wood-Cells—Stomata, or Mouths of Plants—The Camera Lucida, and Mode of Using—Spiral and Ringed Vessels—Hairs of Plants—Resins, Scents, and Oils—Bark Cells.

We will now suppose the young observer to have obtained a microscope and learned the use of its various parts, and will proceed to work with it. As with one or two exceptions, which are only given for the purpose of further illustrating some curious structure, the whole of the objects figured in this work can be obtained without any difficulty, the best plan will be for the reader to procure the plants, insects, etc., from which the objects are taken, and follow the book with the microscope at hand. It is by far the best mode of obtaining a systematic knowledge of the matter, as the quantity of objects which can be placed under a microscope is so vast that, without some guide, the tyro flounders hopelessly in the sea of unknown mysteries, and often becomes so bewildered that he gives up the study in despair of ever gaining any true knowledge of it. I would therefore recommend the reader to work out the subjects which are here mentioned, and then to launch out for himself on the voyage of discovery. I speak from experience, having myself known the difficulties under which a young and inexperienced observer has to labour in so wide a field, without any guide to help him to set about his work in a systematic manner.

The objects that can be most easily obtained are those of a vegetable nature, as even in London there is not a square, an old wall, a greenhouse, a florist’s window, or even a greengrocer’s shop, that will not afford an exhaustless supply of microscopic employment. Even the humble vegetables that make their daily appearance on the dinner-table are highly interesting; and in a crumb of potato, a morsel of greens, or a fragment of carrot, the enthusiastic observer will find occupation for many hours.

Following the best examples, we will commence at the beginning, and see how the vegetable structure is built up of tiny particles, technically called “cells.”

That the various portions of every vegetable should be referred to the simple cell is a matter of some surprise to one who has had no opportunity of examining the vegetable structure, and indeed it does seem more than remarkable that the tough, coarse bark, the hard wood, the soft pith, the green leaves, the delicate flowers, the almost invisible hairs, and the pulpy fruit, should all start from the same point, and owe their origin to the simple vegetable cell. This, however, is the case; and by means of a few objects chosen from different portions of the vegetable kingdom, we shall obtain some definite idea of this curious phenomenon.

I.

I.

On Plate I. Fig. 1, may be seen three cells of a somewhat globular form, taken from the common strawberry. Any one wishing to examine these cells for himself may readily do so by cutting a very thin slice from the fruit, putting it on a slide, covering it with a piece of thin glass (which may be cheaply bought at the optician’s, together with the glass slides on which the objects are laid), and placing it under a power of two hundred diameters. Should the slice be rather too thick, it may be placed in the live-box and well squeezed, when the cells will exhibit their forms very distinctly. In their primary form the cells seem to be spherical; but as in many cases they are pressed together, and in others are formed simply by the process of subdivision, the spherical form is not very often seen. The strawberry, being a soft and pulpy fruit, permits the cells to assume a tolerably regular form, and they consequently are more or less globular.

Where the cells are of nearly equal size, and are subjected to equal pressure in every direction, they force each other into twelve-sided figures, having the appearance under the microscope of flat six-sided forms. Fig. 8, in the same Plate, taken from the stem of a lily, is a good example of this form of cell, and many others may be found in various familiar objects.

We must here pause for a moment to define a cell before we proceed further.

The cell is a close sac or bag formed of a substance called from its function “cellulose,” and containing certain semi-fluid contents as long as it retains its life. In the interior of the cell may generally be found a little dark spot, termed the “núcleus,” and which may be seen in Fig. 1, to which we have already referred. The object of the nucleus is rather a bone of contention among the learned, but the best authorities on this subject consider it to be the vital centre of the cells, to and from which tends the circulation of the protoplasm, and which is intimately connected with the growth and reproduction of the cell. On looking a little more closely at the nucleus, we shall find it marked with several small light spots, which are termed “nucléoli.”

On the same Plate (Fig. 2) is a pretty group of cells taken from the internal layer of the buttercup leaf, and chosen because they exhibit the series of tiny and brilliant green dots to which the colour of the leaf is due. The technical name for this substance is “chlorophyll,” or “leaf-green,” and it may always be found thus dotted in the leaves of different plants, the dots being very variable in size, number, and arrangement. A very fine object for the exhibition of this point is the leaf of Anácharis , the “Canadian timber-weed,” to be found in almost every brook and river. It also shows admirably the circulation of the protoplasm in the cell.

In the centre of the same Plate (Fig. 12) is a group of cells from the pith of the elder-tree. This specimen is notable for the number of little “pits” which may be seen scattered across the walls of the cells, and which resemble holes when placed under the microscope. In order to test the truth of this appearance, the specimen was coloured blue by the action of iodine and dilute sulphuric acid, when it was found that the blue tint spread over the pits as well as the cell-walls, showing that the membrane is continuous over the pits.

Fig. 7exhibits another form of cell, taken from the Spargánium, or bur-reed. These cells are tolerably equal in size, and have assumed a square shape. They are obtained from the lower part of the leaf. The reader who has any knowledge of entomology will not fail to observe the similarity in form between the six-sided and square cells of plants and the hexagonal and square facets of the compound eyes of insects and crustaceans. In a future page these will be separately described.

Sometimes the cells take most singular and unexpected shapes, several examples of which will be briefly noticed.

In certain loosely made tissues, such as are found in the rushes and similar plants, the walls of the cells grow very irregularly, so that they push out a number of arms which meet each other in every direction, and assume the peculiar form which is termed “stellate,” or star-shaped tissue. Fig. 3shows a specimen of stellate tissue taken from the seed-coat of the privet, and rather deeply coloured, exhibiting clearly the beautiful manner in which the arms of the various stars meet each other. A smaller group of stellate cells taken from the stem of a large rush, and exemplifying the peculiarities of the structure, are seen in Fig. 4.

The reader will at once see that this mode of formation leaves a vast number of interstices, and gives great strength with little expenditure of material. In water-plants, such as the reeds, this property is extremely valuable, as they must be greatly lighter than the water in which they live, and at the same time must be endowed with considerable strength in order to resist its pressure.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Common Objects of the Microscope»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Common Objects of the Microscope» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Common Objects of the Microscope» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.