Louis Becke - The Naval Pioneers of Australia

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Louis Becke - The Naval Pioneers of Australia» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_prose, literature_19, foreign_antique, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Naval Pioneers of Australia

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Naval Pioneers of Australia: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Naval Pioneers of Australia»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Naval Pioneers of Australia — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Naval Pioneers of Australia», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

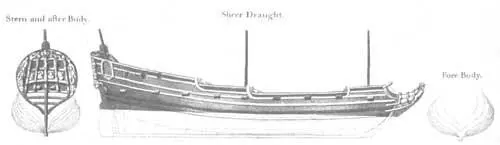

A vessel of this kind was ship-rigged, about 88 feet long by 24 feet beam; the depth of her hold, in which to store her twenty months' provisions (a marvellously large quantity as stores were then carried), was about 11 feet, and her draught of water when loaded about 12 feet aft. She had one deck and a poop and forecastle, the former extending from either end of the ship to the waist. A good deal of superfluous ornament had by this time been done away with, although there was plenty of it so late as 1689. Charnock describes a man-of-war of that date. After the Restoration, ships grew apace in grandeur in and out. Inboard they were painted a dull red (this was, it is said, so that in fighting the blood of the wounded should not show), outside blue and gilded in the upper parts, then yellow, and last black to the water-line, with white bottoms. Copper sheathing had not come into use, and ships' bottoms were treated with tallow, which was made to adhere by being laid on between nails which studded the bottom.

The pitching of the vessels imperilled the masts of these somewhat cranky ships of 1689, says a writer of about Dampier's time, who also tells us that ships then had awnings, and that "glass lanthorns were worthier best made of crystal horn; lanthorns were worthier than isinglass."

The sails were the usual courses: big topsails and topgallantsails, staysails, and topmastsails, with a spritsail and a lateen-mizen; the spanker and jib were not yet, but the sprit-topsail had just gone out. The ship when rigged and fitted ready for sea probably cost King William's Admiralty about £10,000. But the Roebuck was pretty well worn out when Dampier was given the command of her, as he tells us when relating her subsequent loss.

The British Fleet , by Commander C.N. Robinson, is an invaluable book to the student of naval history, and, notwithstanding plenty of book authorities and ten years' study of the subject, the present writers are compelled to draw upon Commander Robinson for many details. With the aid of this work and from allusions to be found in the writings of a couple of centuries ago, it is possible to make some sort of picture of Dampier's companions in the Roebuck .

Dampier himself was a type of naval officer who entered the service of the country by what was then, and remained for many years afterwards, one of the best sources of supply. He had been given a fair education, and had been duly apprenticed and learned the profession of a sailor in a merchant ship. Upon his return from his first voyage to the South Seas he published an account of his travels, and dedicated it to the President of the Royal Society, the Hon. Charles Mountague, who, appreciating the author's zeal and his intelligent public spirit, recommended him to the patronage of the Earl of Oxford, then Principal Lord of the Admiralty. Dampier's dedication has nothing of the fulsome flattery and begging-letter style so often the chief characteristic of such compositions, but is the straightforward offer of a humble worker in science of the best of his work to the man best able to appreciate and to make the most of it. Dampier's dedication led to his appointment in the navy, and the transaction does honour to both the patron and him who was patronized.

As is well known, until comparatively recent times only the officers of the fighting branch held commissions; all others were either warrant or petty officers. In the time of William III., a captain and one lieutenant were allowed to each ship, and none of the other officers held commissions. The peaceful mission of the Roebuck justifies us in concluding that Dampier held the King's commission as a lieutenant commanding, and he was probably given a lieutenant to take charge in case of accident, a master, a couple of master's mates, a gunner, a boatswain and carpenter, and the usual petty officers; seamen and boys made up the complement. Dampier's pay, so far as we can ascertain, would be at the rate of about £12 per month.

Two regiments of marine infantry had been formed so early as 1689, but they were disbanded nine years later. It was not until 1703 that the marines, all infantry, became a permanent branch of the service.

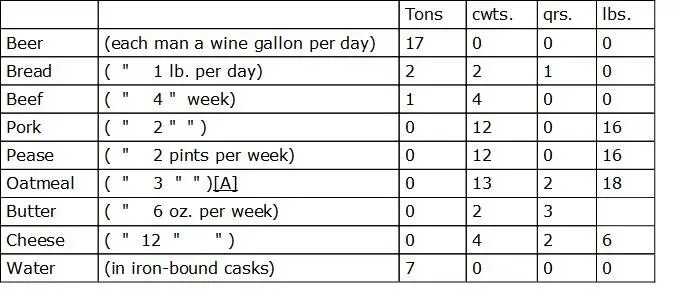

Uniforms had not even been thought of at this time, and the Roebuck's officers, from her commander downwards, ate and drank and clothed themselves in much the same fashion as their men. Dampier probably had a room right aft under the long poop, and the other officers at the same end of the ship in canvas-partitioned cabins, the fore part of her one living deck being occupied by the crew. There was probably a mess-room under the poop common to all the officers. What they had to eat and drink, as we have said, was the same for all ranks. Here is a scale of provisions for eighty-five men of a sixth-rate of 1688 for two months, taken from Charnock:—

[A] In lieu of three eighths of a fish.

In 1690 flour and raisins were added, and an effort made to condense water. Beer took the place of all forms of drink, and water was at that time carried in casks.

The dress, from contemporary prints, can be easily made out, and the allusions of Pepys and Evelyn supply the names and materials of the garments. Pepys' diary and letters inform us how the pursers of the time supplied the men with slops, and in The British Fleet considerable detail on this subject is given. Roughly it may be assumed that Dampier's sailors wore petticoats and breeches, grey kersey jackets, woollen stockings and low-heeled shoes, and worsted, canvas, or leather caps. Canvas, leather, and coarse cloth were the principal materials, and tin buttons and coloured thread the most ornamental part, of the costume. Charnock says that in 1663 "sailors began first to wear distinctive dress. A rule was that only red caps, yarn and Irish stockings, blue shirts, white shirts, cotton waistcoats, cotton drawers, neat leather flat-heeled shoes, blue neckcloths, canvas suits, and rugs were to be sold to them. Red breeches were worn."

Smollett's pictures of the service in Roderick Random , written forty years after Dampier's time, give us some idea of life on board ship, for in the forty years between the two dates it differed in no essential particulars. Pepys describes a sailor who had lost his eye in action having the socket plugged with oakum, a fact which tells more than could a volume of how seamen were then cared for. It was the days of the press and of the advance-note system, which prevailed well into the present century, and those seamen who went with Dampier of their own free will on a voyage where nothing but the poorest pay and no prize money was to be got were probably the lowest and most ill-disciplined rascals, drawn from a class upon whose characters, save for their bulldog courage and reckless prodigality, the least written the better.

The modern bluejacket, superior in every respect, notwithstanding certain croakers, is infinitely better than his ancestors in the very quality which was their best; the modern sailor faces death soberly and decently in forms far more terrible than were ever dreamt of by his forefathers. When the Calliope steamed out of Apia Harbour in the hurricane of March, 1889, the youngest grimy coal-trimmer, whose sole duty it was to silently shovel coal, even though his last moment came to him while doing it, never once asked if the ship was making way. All hands in this department were on duty for sixteen hours, and during that time no sound was heard, save the ring of the shovels firing the boilers, nor was a question asked by any man as to the progress of the ship or the chances of life and death.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Naval Pioneers of Australia»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Naval Pioneers of Australia» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Naval Pioneers of Australia» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.