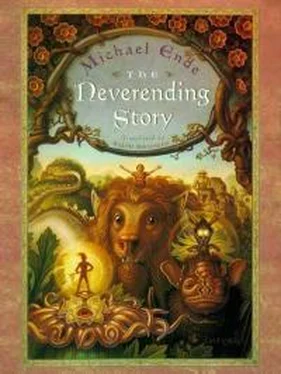

Михаэль Энде - The Neverending Story

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Михаэль Энде - The Neverending Story» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, ISBN: 1997, Издательство: Dutton Children's Books, Жанр: Детская проза, fairy_fantasy, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Neverending Story

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dutton Children's Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:9780525457589

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Neverending Story: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Neverending Story»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Neverending Story — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Neverending Story», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The horse wasn’t running fast enough for him. He was determined to overtake Atreyu and Falkor at all costs, even if it meant riding this metallic monster to its death.

He wanted vengeance! He would have attained the goal of all his wishes if Atreyu hadn’t interfered. Bastian had not become Emperor of Fantastica. And for that he would make Atreyu repent.

The joints of Bastian’s metallic steed ground and creaked louder and louder, but still it obeyed its rider’s will.

Bastian rode for hours and hours through the endless night. In his mind’s eye he saw the flaming Ivory Tower. Over and over he lived the moment when Atreyu had set the point of his sword to his chest. And then for the first time he asked himself why Atreyu had hesitated. Why, after all that had happened, couldn’t he bring himself to strike Bastian and take AURYN by force? And suddenly Bastian thought of the wound he had inflicted on Atreyu and the look in Atreyu’s eyes as he staggered and fell.

Bastian put Sikanda, which up until then he had been clutching in his fist, back into its rusty sheath.

In the first light of dawn he saw he was on a heath. Dark clumps of juniper suggested motionless groups of gigantic hooded monks or magicians with pointed hats.

And then suddenly, in the midst of a frantic gallop, Bastian’s metal steed burst into pieces.

Bastian lay stunned by the violence of his fall. When he finally picked himself up and rubbed his bruised limbs, he found himself in the middle of a juniper bush. He crawled out into the open. The fragments of the horse lay scattered all about, as though an equestrian monument had exploded.

Bastian stood up, threw his black mantle over his shoulders, and with no idea where he was going, started walking in the direction of the rising sun.

But a glittering object was left behind in the juniper bush: the belt Ghemmal. Bastian was unaware of his loss and never thought of the belt again. Ilwan had saved it from the flames for nothing.

A few days later Ghemmal was found by a blackbird, who had no suspicion of what this glittering object might be. She carried it to her nest, but that’s the beginning of another story that shall be told another time.

At midday Bastian came to a high earthen wall that cut across the heath. He climbed to the top of it. Behind it, in a craterlike hollow, lay a city. At least the quantity of buildings made Bastian think of a city, but it was certainly the weirdest one he had ever seen.

The buildings seemed to be jumbled every which way without rhyme or reason, as though they had been emptied at random out of a giant sack. There were neither streets nor squares nor was there any recognizable order.

And the buildings themselves were crazy; they had “front doors” in their roofs, stairways which were quite inaccessible and ended in the middle of nowhere; towers slanted, balconies dangled vertically, there were doors where one would have expected windows, and floors in the place of walls. Bridges stopped halfway, as though the builders had suddenly forgotten what they were doing. There were towers bent like bananas and pyramids standing on their tips. In short, the whole city seemed to have gone mad.

Then Bastian saw the inhabitants—men, women, and children. They were built like ordinary human beings, but dressed as if they had lost the power to distinguish between clothing and objects intended for other purposes. On their heads they wore lampshades, sand pails, soup bowls, wastepaper baskets, or shoe boxes. Their bodies were swathed in towels, carpets, big sheets of wrapping paper, or barrels.

Many were pushing or pulling handcarts with all sorts of junk piled up on them, broken lamps, mattresses, dishes, rags, and knick-knacks. Others were carrying enormous bales slung over their shoulders.

The farther Bastian went into the city, the thicker became the crowd. But none of the people seemed to know where they were going. Several times Bastian saw someone dragging a heavily laden cart in one direction, then after a short time doubling back, and a few minutes later changing direction again. Everybody was feverishly Active.

Bastian decided to speak to one of these people.

“What’s the name of this place?”

The person let go his cart, straightened up, and scratched his head for a while as though thinking it over. Then he went away, abandoning his cart, which he seemed to have forgotten. But a few minutes later, a woman took hold of the cart and started off with it. Bastian asked her if the junk was hers. The woman stood for a while, deep in thought. Then she too went away.

Bastian tried a few more times but received no answer.

Suddenly he heard someone giggling. “No point in asking them,” said the giggler. “They can’t tell you anything. One might, in a manner of speaking, call them the Know-Nothings.”

Bastian turned toward the voice and saw a little gray monkey sitting on a window ledge, or rather on what would have been a window ledge if the window hadn’t been upside down. The animal was wearing a mortarboard with a dangling tassel and seemed to be busy counting something on his fingers and toes. When he had finished, he grinned and said: “Sorry to keep you waiting, sir, but there was something I had to figure out.”

“Who are you?” Bastian asked.

“My name is Argax,” said the little monkey, lifting his mortarboard. “Pleased to meet you. And with whom have I the pleasure?”

“My name is Bastian Balthazar Bux.”

“Just as I thought,” said the monkey, visibly pleased.

“And what is the name of this city?” Bastian inquired.

“It hasn’t actually got a name,” said Argax. “But one might, in a manner of speaking, call it the City of the Old Emperors.”

“Old Emperors?” Bastian repeated with consternation. “Why, I don’t see anybody who looks like an Old Emperor.”

“You don’t?” said the monkey with a giggle. “Well, believe it or not, all the people you’ve seen were Emperors of Fantastica in their time—or wanted to be.”

Bastian was aghast.

“How do you know that, Argax?”

The monkey lifted his mortarboard and grinned.

“I, in a manner of speaking, am the superintendent here.”

Bastian looked around. Not far away an old man had dug a pit. He put a lighted candle into it, then shoveled earth over the candle.

The monkey giggled. “What would you say to a little tour of the town, sir? To get acquainted, in a manner of speaking, with your future residence.”

“No,” said Bastian. “What are you talking about?”

The monkey jumped up on his shoulder. “Let’s go,” he whispered. “It’s free of charge. You’ve already paid the admission fee.”

Bastian obeyed the monkey’s orders, though he would rather have run away. He grew more miserable with every step. He watched the people and was struck by the fact that they didn’t talk. They were all so busy with their own concerns that they didn’t even seem to see one another.

“What’s wrong with them?” Bastian asked. “Why are they so odd?”

“Nothing odd about them!” said Argax. “They’re just like you, in a manner of speaking, or rather, they were in their time.”

Bastian stopped in his tracks. “What do you mean by that? Do you mean that they’re humans?”

Argax jumped up and down on Bastian’s shoulder. “Exactly!” he said gleefully.

Bastian saw a woman in the middle of the street trying to spear peas with a darning needle.

“How did they get here? What are they doing here?”

“Oh, there have always been humans who couldn’t find their way back to their world,” Argax explained. “First they didn’t want to, and now, in a manner of speaking, they can’t.”

Bastian looked at a little girl who was struggling to push a doll’s carriage with square wheels.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Neverending Story»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Neverending Story» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Neverending Story» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.