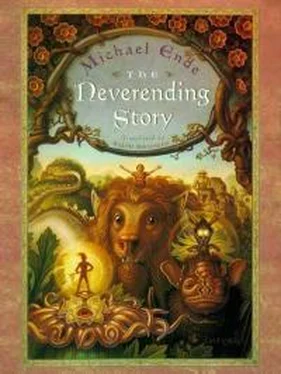

Михаэль Энде - The Neverending Story

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Михаэль Энде - The Neverending Story» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, ISBN: 1997, Издательство: Dutton Children's Books, Жанр: Детская проза, fairy_fantasy, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Neverending Story

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dutton Children's Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:9780525457589

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Neverending Story: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Neverending Story»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Neverending Story — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Neverending Story», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

She stopped to rest and looked up. She still had a long way to go. So far she hadn’t even gone halfway.

“Old Man of Wandering Mountain,” she said aloud. “If you don’t want us to meet, you needn’t have written me this ladder. It’s your disinvitation that brings me.”

And she went on climbing. WHAT YOU ACHIEVE AND WHAT YOU ARE IS RECORDED BY ME, THE CHRONICLER. LETTERS UNCHANGEABLE AND DEAD FREEZE WHAT THE LIVING DID AND SAID. THEREFORE BY COMING HERE TO ME YOU INVITE CATASTROPHE. THUS IS THE END OF WHAT YOU ONCE BEGAN. YOU WILL NEVER BE OLD, AND I, OLD MAN WAS NEVER YOUNG. WHAT YOU AWAKEN I LAY TO REST. BE NOT MISTAKEN: IT IS FORBIDDEN THAT LIFE SHOULD SEE ITSELF IN DEAD ETERNITY.

Again she had to stop to catch her breath.

By then the Childlike Empress was high up and the ladder was swaying like a branch in the snowstorm. Clinging to the icy letters that formed the rungs of the ladder, she climbed the rest of the way. BUT IF YOU STILL REFUSE TO HEED THE WARNING OF THE LADDER’S SCREED, IF YOU ARE STILL PREPARED TO DO WHAT IN TIME AND SPACE IS FORBIDDEN YOU, I WON’T ATTEMPT TO HOLD YOU BACK, THEN WELCOME TO THE OLD MAN’S SHACK.

When the Childlike Empress had those last rungs behind her, she sighed and looked down. Her wide white gown was in tatters, for it had caught on every bend and crossbar of the message-ladder. Oh well, she had known all along that letters were hostile to her. She felt the same way about them.

From the ladder she stepped through the circular opening in the egg. Instantly it closed behind her, and she stood motionless in the darkness, waiting to see what would happen next.

Nothing at all happened for quite some time.

At length she said softly: “Here I am.” Her voice echoed as in a large empty room—or was it another, much deeper voice that had answered her in the same words?

Little by little, she made out a faint reddish glow in the darkness. It came from an open book, which hovered in midair at the center of the egg-shaped room. It was tilted in such a way that she could see the binding, which was of copper-colored silk, and on the binding, as on the Gem, which the Childlike Empress wore around her neck, she saw an oval formed by two snakes biting each other’s tail. Inside this oval was printed the title:

The Neverending Story

Bastian’s thoughts were in a whirl. This was the very same book that he was reading! He looked again. Yes, no doubt about it, it was the book he had in his hand. How could this book exist inside itself?

The Childlike Empress had come closer. On the other side of the hovering book she now saw a man’s face. It was bathed in a bluish light. The light came from the print of the book, which was bluish green.

The man’s face was as deeply furrowed as if it had been carved in the bark of an ancient tree. His beard was long and white, and his eyes were so deep in their sockets that she could not see them. He was wearing a dark monk’s robe with a hood, and in his hand he was holding a stylus, with which he was writing in the book. He did not look up.

The Childlike Empress stood watching him in silence. He was not really writing. His stylus glided slowly over the empty page and the letters and words appeared as though of their own accord.

The Childlike Empress read what was being written, and it was exactly what was happening at that same moment: “The Childlike Empress read what was being written . . .”

“You write down everything that happens,” she said.

“Everything that I write down happens,” was the answer, spoken in the deep, dark voice that had come to her like an echo of her own voice.

Strange to say, the Old Man of Wandering Mountain had not opened his mouth. He had written her words and his, and she had heard them as though merely remembering that he had just spoken. “Are you and I and all Fantastica,” she asked, “are we all recorded in this book?”

He wrote, and at the same time she heard his answer: “No, you’ve got it wrong. This book is all Fantastica—and you and I.”

“But where is this book?”

And he wrote the answer: “In the book.”

“Then it’s all a reflection of a reflection?” she asked.

He wrote, and she heard him say: “What does one see in a mirror reflected in a mirror? Do you know that, Golden-eyed Commander of Wishes?”

The Childlike Empress said nothing for a while, and the Old Man wrote that she said nothing.

Then she said softly: “I need your help.”

“I knew it,” he said and wrote.

“Yes,” she said. “I supposed you would. You are Fantastica’s memory, you know everything that has happened up to this moment. But couldn’t you leaf ahead in your book and see what’s going to happen?”

“Empty pages,” was the answer. “I can only look back at what has happened. I was able to read it while I was writing it. And I know it because I have read it. And I wrote it because it happened. The Neverending Story writes itself by my hand.”

“Then you don’t know why I’ve come to you?”

“No.” And as he was writing, she heard the dark voice: “And I wish you hadn’t. By my hand everything becomes fixed and final—you too, Golden-eyed Commander of Wishes. This egg is your grave and your coffin. You have entered into the memory of Fantastica. How do you expect to leave here?”

“Every egg,” she said, “is the beginning of new life.”

“True,” the Old Man wrote and said, “but only if its shell bursts open.”

“You can open it,” cried the Childlike Empress. “You let me in.”

“Your power let you in. But now that you’re here, your power is gone. We are shut up here for all time. Truly, you shouldn’t have come. This is the end of the Neverending Story.”

The Childlike Empress smiled. She didn’t seem troubled in the least.

“You and I,” she said, “can’t prolong it. But there is someone who can.”

“Only a human,” wrote the Old Man, “can make a fresh start.”

“Yes,” she replied, “a human.”

Slowly the Old Man of Wandering Mountain raised his eyes and saw the Childlike Empress for the first time. His gaze seemed to come from the darkest distance, from the end of the universe. She stood up to it, answered it with her golden eyes. A silent, immobile battle was fought between them. At length the Old Man bent over his book and wrote: “For you too there is a borderline. Respect it.”

“I will,” she said, “but the one of whom I speak, the one for whom I am waiting, crossed it long ago. He is reading this book while you are writing it. He hears every word we are saying. He is with us.”

“That is true!” she heard the Old Man’s voice as he was writing. “He too is part and parcel of the Neverending Story, for it is his own story.”

“Tell me the story!” the Childlike Empress commanded. “You, who are the memory of Fantastica—tell me the story from the beginning, word for word as you have written it.”

The Old Man’s writing hand began to tremble.

“If I do that, I shall have to write everything all over again. And what I write will happen again.”

“So be it!” said the Childlike Empress.

Bastian was beginning to feel uncomfortable.

What was she going to do? It had something to do with him. But if even the Old Man of Wandering Mountain was trembling . . .

The Old Man wrote and said: “If the Neverending Story contains itself, then the world will end with this book.”

And the Childlike Empress answered: “But if the hero comes to us, new life can be born. Now the decision is up to him.”

“You are ruthless indeed,” the Old Man said and wrote. “We shall enter the Circle of Eternal Return, from which there is no escape.”

“Not for us,” she replies, and her voice was no longer gentle, but as hard and clear as a diamond. “Nor for him—unless he saves us all.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Neverending Story»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Neverending Story» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Neverending Story» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.