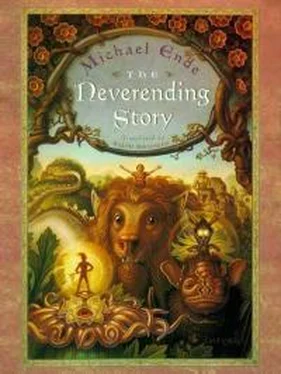

Михаэль Энде - The Neverending Story

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Михаэль Энде - The Neverending Story» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, ISBN: 1997, Издательство: Dutton Children's Books, Жанр: Детская проза, fairy_fantasy, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Neverending Story

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dutton Children's Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:9780525457589

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Neverending Story: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Neverending Story»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Neverending Story — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Neverending Story», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Atreyu was overjoyed.

“I hated leaving you to Ygramul,” said. “But what could I do?”

“Nothing,” said the luckdragon. “You’ve saved my life all the same—even if I had something to do with it.”

And again he winked, this time with the other eye.

“Saved your life,” Atreyu repeated, “for an hour. That’s all we have left. I can feel Ygramul’s poison burning my heart away.”

“Every poison has its antidote,” said the white dragon. “Everything will turn out all right. You’ll see.”

“I can’t imagine how,” said Atreyu.

“Neither can I,” said the luckdragon. “But that’s the wonderful part of it. From now on you’ll succeed in everything you attempt. Because I’m a luckdragon. Even when I was caught in the web, I didn’t give up hope. And as you see, I was right.”

Atreyu smiled.

“Tell me, why did you wish yourself here and not in some other place where you might have been cured?”

“My life belongs to you,” said the dragon, “if you’ll accept it. I thought you’d need a mount for this Great Quest of yours. And you’ll soon see that crawling around the country on two legs, or even galloping on a good horse, can’t hold a candle to whizzing through the air on the back of a luckdragon. Are we partners?”

“We’re partners,” said Atreyu.

“By the way,” said the dragon. “My name is Falkor.”

“Glad to meet you,” said Atreyu, “but while we’re talking, what little time we have left is seeping away. I’ve got to do something. But what?”

“Have luck,” said Falkor. “What else?”

But Atreyu heard no more. He had fallen down and lay motionless in the soft folds of the dragon’s body.

Ygramul’s poison was taking effect.

When Atreyu—no one knows how much later—opened his eyes again, he saw nothing but a very strange face bent over him. It was the wrinkliest, shriveledest face he had ever seen, and only about the size of a fist. It was as brown as a baked apple, and the eyes in it glittered like stars. The head was covered with a bonnet made of withered leaves.

Atreyu felt a little drinking cup held to his lips.

“Nice medicine! Good medicine!” mumbled the wrinkled little lips in the shriveled face. “Just drink, child. Do you good.”

Atreyu sipped. It tasted strange. Kind of sweet and sour.

Atreyu found it painful to speak. “What about the white dragon?” he asked.

“Doing fine!” the voice whispered. “Don’t worry, my boy. You’ll get well. You’ll both get well. The worst is over. Just drink. Drink.”

Atreyu took another swallow and again sleep overcame him, but this time it was the deep, refreshing sleep of recovery.

The clock in the belfry struck two.

Bastian couldn’t hold it in any longer. He simply had to go. He had felt the need for quite some time, but he hadn’t been able to stop reading. Besides, he had been afraid to go downstairs. He told himself that there was nothing to worry about, that the building was deserted, that no one would see him. But still he was afraid, as if the school were a person watching him.

But in the end there was no help for it; he just had to go!

He set the open book down on the mat, went to the door and listened with pounding heart. Nothing. He slid the bolt and slowly turned the big key in the lock. When he pressed the handle, the door opened, creaking loudly.

He padded out in his stocking feet, leaving the door behind him open to avoid unnecessary noise. He crept down the stairs to the second floor. The students’ toilet was at the other end of the long corridor with the spinach-green classroom doors. Racing against time, Bastian ran as fast as he could—and just made it.

As he sat there, he wondered why heroes in stories like the one he was reading never had to worry about such problems. Once—when he was much younger—he had asked his religion teacher if Jesus Christ had had to go like an ordinary person. After all, he had taken food and drink like everyone else. The class had howled with laughter, and the teacher, instead of an answer, had given him several demerits for “insolence”. He hadn’t meant to be insolent.

“Probably,” Bastian now said to himself, “these things are just too unimportant to be mentioned in stories.”

Yet for him they could be of the most pressing and embarrassing importance.

He was finished. He pulled the chain and was about to leave when he heard steps in the corridor outside. One classroom door after another was opened and closed, and the steps came closer and closer.

Bastian’s heart pounded in his throat. Where could he hide? He stood glued to the spot as though paralyzed.

The washroom door opened, luckily in such a way as to shield Bastian. The janitor came in. One by one, he looked into the stalls. When he came to the one where the water was still running and the chain swaying a little, he hesitated for a moment and mumbled something to himself. But when the water stopped running he shrugged his shoulders and went out. His steps died away on the stairs.

Bastian hadn’t dared breathe the whole time, and now he gasped for air. He noticed that his knees were trembling.

As fast as possible he padded down the corridor with the spinach-green doors, up the stairs, and back into the attic. Only when the door was locked and bolted behind him did he relax.

With a deep sigh he settled back on his pile of mats, wrapped himself in his army blankets, and reached for the book.

When Atreyu awoke for the second time, he felt perfectly rested and well. He sat up.

It was night. The moon was shining bright, and Atreyu saw he was in the same place where he and the white dragon had collapsed. Falkor was still lying there. His breathing came deep and easy and he seemed to be fast asleep. His wounds had been dressed.

Atreyu noticed that his own shoulder had been dressed in the same way, not with cloth but with herbs and plant fibers.

Only a few steps away there was a small cave, from which issued a faint beam of light.

Taking care not to move his left arm, Atreyu stood up cautiously and approached the cave. Bending down—for the entrance was very low—he saw a room that looked like an alchemist’s workshop in miniature. At the back an open fire was crackling merrily. Crucibles, retorts, and strangely shaped flasks were scattered all about. Bundles of dried plants were piled on shelves. The little table in the middle of the room and the other furniture seemed to be made of root wood, crudely nailed together.

Atreyu heard a cough, and then he saw a little man sitting in an armchair by the fire. The little man’s hat had been carved from a root and looked like an inverted pipe bowl. The face was as brown and shriveled as the face Atreyu had seen leaning over him when he first woke up. But this one was wearing big eyeglasses, and the features seemed sharper and more anxious. The little man was reading a big book that was lying in his lap.

Then a second little figure, which Atreyu recognized as the one that had bent over him, came waddling out of another room. Now Atreyu saw that this little person was a woman. Apart from her bonnet of leaves, she—like the man in the armchair—was wearing a kind of monk’s robe, which also seemed to be made of withered leaves.

Humming merrily, she rubbed her hands and busied herself with a kettle that was hanging over the fire. Neither of the little people would have reached up to Atreyu’s knee.

Obviously they belonged to the widely ramified family of the gnomes, though to a rather obscure branch.

“Woman!” said the little man testily. “Get out of my light. You are interfering with my research!”

“You and your research!” said the woman. “Who cares about that? The important thing is my health elixir. Those two outside are in urgent need of it.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Neverending Story»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Neverending Story» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Neverending Story» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.