The dancing bears were the last to go. It was as if they could hardly tear themselves away from the yetis, and even when they had shuffled off into the darkness, they came back again and again to rub themselves once more against their rescuers.

But at last the zoo was empty and the yetis were just turning to go back to the lorry when Lucy said: “Where’s Ambrose? And what’s that splash?”

What that splash was, was Mr. Bullaby, the head keeper, whom Ambrose the Abominable had just thrown into the crocodile pond.

“I found him in his house, hiding under the bed,” said Ambrose, when the others ran up to him, “and I thought he ought to be punished. Lady Agatha always punished us when we were naughty, and this zoo is more than naughty, isn’t it?”

The yetis stood round solemnly in the moonlight, watching Mr. Bullaby in his yellow silk pajamas, floundering and spluttering in the filthy pool.

“Was I wrong to do it?” asked Ambrose, suddenly growing anxious.

But the others, remembering the pitiful things they had seen that night, said no, he hadn’t been.

“If the crocodiles had still been there, you shouldn’t have done it,” said Lucy, “because it wouldn’t have been fair on the crocodiles. But they weren’t. So you should’ve.”

And then they all padded quietly out of the zoo and climbed back into the lorry and fell asleep.

Con, curled up in the cab in front, was having a most peculiar dream. He dreamed that a large and rather loopy-looking gnu was looking in at the lorry window.

Making an effort, he opened his eyes, stretched …

A large and loopy-looking gnu was looking in at the lorry window.

“Goodness!” said Con. But before he could explore further, Perry came back from the all-night garage carrying the mended pump. “The place’s gone mad,” he said. “There’s a tree sloth hanging from the lamppost, a couple of kangaroos are window-shopping in the square, and—” He broke off. “Good Lord! Look at the zoo!”

In silence, Perry and the children stared across the little park at the broken fences, the shattered buildings …

“Is it an earthquake, do you think?” asked Ellen, who’d only just woken up and was still rather muddled.

“Or a terrorist letting off bombs?” suggested Con.

But before they could decide how the zoo had got into the state it was in, there was an agitated scrabbling from the container, and when Con cautiously opened the door, all five yetis stood looking out at him, beaming with pride and joy.

“We did it! It’s a surprise for you! We let out all the animals, every single one!” said Ambrose the Abominable.

There was a moment of total silence while Con took this in. “Oh, no! You didn’t! Say you didn’t!” he begged.

“But we did. All the animals were sad , so—”

Con’s face had turned ashen. He had begun to tremble. “Don’t you see, it’s a crime . Breaking up people’s property, smashing things … As soon as the Sultan gets to hear of it, he’ll send his soldiers with machine guns. You’ll be mown down, you’ll be—”

But Perry now came to the rescue. “We’re only a hundred miles from the border,” he said, “and the Sultan can’t touch us once we’re across. The pump’s mended; no one’s about yet — we’ve a good chance of making a getaway.”

And a few seconds later the door had shut on the bewildered yetis and the yellow lorry was roaring out of the city.

A hundred miles in a slow and overloaded lorry can seem like a desperately long way. Every motor horn, every train whistle made the children jump as they imagined the Sultan’s men come to round up the yetis or torture them or simply shoot them out of hand.

But the Sultan did not come that day, or any other day. And that was because, by evening, the city of Aslerfan no longer had a sultan.

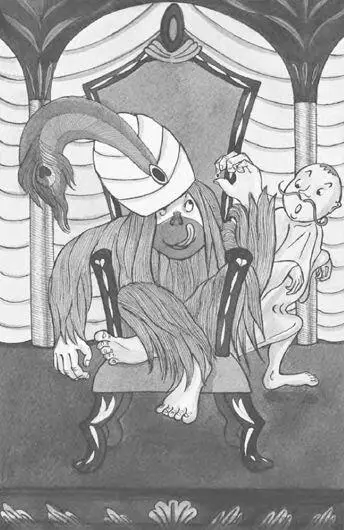

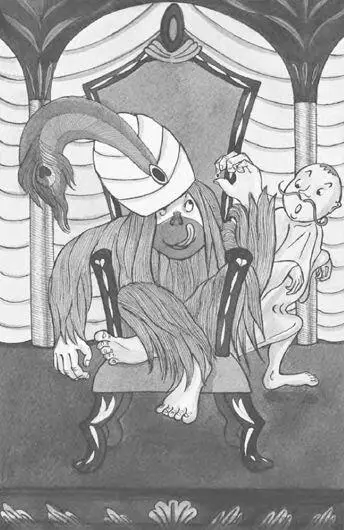

What happened was this. On the morning that the yellow lorry left Aslerfan, the cruel and greedy little Sultan woke up in his huge gold-and-turquoise bed as he did each day, stretched his fat little arms as he did each day, and thought of all the nice things he was going to do, like watch a public execution, have some journalists flogged because they’d dared to criticize him in their newspapers, and arrange a hunt in which a herd of exquisite fallow deer would be gunned down from his private fleet of helicopters.

Then, as he did every day, he rang for his servants. But after that, things happened differently. Because what came into the room was not his barber to shave him, or his valet to dress him, or his footman carrying the six fried eggs he always ate for breakfast.

It was a hippopotamus.

“Help!” screamed the Sultan. “Help! Help!” He reached for the bell rope and pulled it again. Only it was not the bell rope. It was the tail of an enormous boa constrictor, which now fell in a hissing and annoyed heap onto the Sultan’s embroidered counterpane.

“Aaeee!” yelled the Sultan. He leaped out of bed and rushed for the nearest door, which led into his lapis-lazuli-and-marble bathroom.

Sitting quietly in the middle of the bath was a huge, whiskery, and very wrinkled walrus.

“It’s a plague! It’s a plague of animals! The gods have decided to punish me!” yelled the Sultan, who had read about the great plagues of Egypt, when Jehovah had sent locusts and frogs and flies to punish a wicked ruler who had been cruel to his people.

As the terrified Sultan ran through the corridors of his palace, he saw more and more signs that the gods were out to get him. An orangutan was sitting on the imperial throne, dreamily cracking fleas between his teeth; a proud ostrich had just laid an egg on the grand piano in the music room; and three armadillos were bulldozing their way across the table in the state dining hall …

Still in his pajamas, the fat little man reached the main courtyard. There was no sign of his servants or his soldiers, who had all fled when the animals invaded the palace. But standing by the fountain, looking at him through golden, serious eyes, were two very stripy tigers.

The Sultan waited no longer. With a scream of terror he turned and ran, on and on, through his terraced gardens and private parks and pleasure pavilions, on and on, till he came to the brown bare hills that surrounded the city. And there he fell on his knees and beat his head against the earth and asked the gods to forgive him his sins. And the next day he put on a sacking robe and went to live in a cave, where he spent the rest of his life gabbling prayers and fasting so that he would get to heaven in the end.

And so the hated Sultan was seen no more, and in the city of Aslerfan there was feasting and rejoicing and dancing in the streets. People hugged each other and let off fireworks and threw open the doors of their cafés so that everyone could eat and drink their fill. The prisoners were let out of their dungeons and the sick were taken off the streets and cared for. But because it was the animals who had brought freedom to the people, the new government made it a law that all the animals that had escaped were to be guests of the city and not to be harmed. So, for many months, while they built a new, model zoo for those animals that preferred to live in town, you could see cars edging around giraffes dozing in the middle of the road, barbers politely shaving wildebeests who had wandered into their shops, or old ladies giving lifts to porcupines in their shopping baskets.

Читать дальше