“Heil, Hitler!” said the colonel, and Gambetti cleared his throat and said, “Heil, Hitler,” in a slightly squeaky voice.

“I have messages for you from our headquarters. The chief of the Gestapo is appreciative of the information you have sent to us. I take it there has been no change?”

“Not as far as I know, Colonel,” said Gambetti.

“Good. Good. In that case I think it is time for us to act for the good of your beautiful country. We have great affection for Bergania — I used to come skiing here with my family when the children were small. It will be a pleasure for us to rescue the country from the king’s obstinacy and folly.”

Baron Gambetti nodded. “It seems impossible to make him see that there is no future for countries that oppose the might and strength of Germany. We must join the great German Reich or be trampled underfoot. But the king is obstinate — his prime minister, too, old von Arkel. He will never give in to Herr Hitler’s demands, which are, after all, not unreasonable. As a Berganian patriot I feel it is my duty to help you,” he said.

“Quite so,” said Stiefelbreich. “In that case we had better get down to details.”

An hour later Gambetti let himself into his villa behind the botanical gardens and found his wife in her dressing room.

“I hope you didn’t weaken, Philippe,” she said. “If we dither now, we are lost.”

“No, I didn’t weaken. But I hope he means what he says. That everything will be… civilized… an orderly takeover without any bloodshed or violence.”

“Of course he means it,” said his wife, taking the curlers out of her dyed blonde hair. “It will be perfectly simple. And you will at last have the honor and glory you deserve. I’m sure he promised you your reward.”

“Yes, he did. Only…”

“Only what? For heaven’s sake — why can’t you be a man?”

“I am being a man,” said Gambetti plaintively. “But it isn’t easy to do this — the king has been good to me.”

“Bah! Milksop,” said the baroness. “Thank goodness you are married to somebody who isn’t afraid of a bit of adventure. Now pass me my hairbrush, please.”

Back in the Blue Ox, Stiefelbreich was questioning his bodyguards.

“Find out if Stilton has arrived — he should be here by now.”

“He has, sir,” said Theophilus. “Checked in to room twenty-three, on the third floor. Next to the attic…”

Stilton, like Earless, was an Englishman. He had led a perfectly normal life for many years, working as a sanitary engineer who specialized in bathroom fittings, so that he earned good money, but after a while he decided it was his duty to travel around the simple peasant houses of Europe and persuade their owners to get rid of their old-fashioned outdoor toilets — just a hole in a wooden bench — and order a proper, indoor, flush sanitation system.

But that wasn’t all he did. Stilton had a hobby — more of a skill , really — and it was because of this that Stiefelbreich had tracked him down. Now, hearing that Stilton had arrived safely, the Nazi smiled and rubbed his hands, knowing that everything would go exactly as planned.

There was only one more thing for Stiefelbreich to do. He picked up the phone and put a call through to the German consulate.

“I take it you have my instructions about the German children at the campsite? I have made inquiries and they are quite unsuitable. Children like that should never have been sent to represent our glorious country and the new order that Herr Hitler has established.”

He listened, frowning, to the voice on the other end. The man seemed to be arguing, almost pleading.

“I’m afraid that has nothing to do with it,” Stiefelbreich barked. “Please see that my orders are carried out without delay.”

Satisfied that the matter was settled, he ordered a large beer. The middle-aged waitress with ginger hair who brought it to him was unfriendly — but it didn’t matter. This infuriating country was about to get a lesson it would not forget.

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

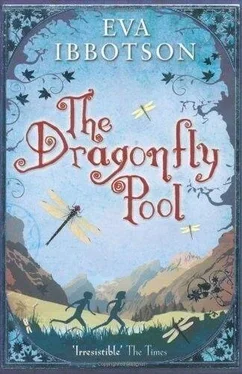

The Dragonfly Pool

They had worked all morning but now, the last day before the festival began, everyone was relaxing. Tally and Julia had finished untangling the wreaths and straightening the flowers for their costumes and were playing cards on the grass with Anneliese, the curly-haired German girl who had befriended them. Borro was demonstrating slingshots to his French friend, whirling his scarf around his head and sending missiles unerringly into the river. Kit and two Dutch boys were trying to catch a carp, lying on their stomachs by the pool and using willpower to make the fish come to the surface.

Matteo was organizing a game of football on a patch of level ground farther along the bank, and Magda was playing chess with the teacher in charge of the German group. He was a serious young man with horn-rimmed spectacles and reminded her of Heribert, the professor she had hoped to marry.

It was a glorious day, sunny and still.

A woman carrying a posy of sweet peas came out of the Blue Ox, and crossed the river and made her way toward the marble statue of the queen. She removed the withered flowers and put the fresh ones in the statue’s hand. As she came back she smiled at the children. It was the middle-aged waitress who had stared at Matteo.

From the Spanish tent came the sound of a guitar, and the dancers in their bright red skirts and yellow boleros made their way to the wooden platform for a last rehearsal. Their music drew a few of the other children to the platform. Those who had been dozing lifted their heads.

“We did it,” said Tally happily. “It worked — here we all are from everywhere.”

And their new friend nodded and taught them a German word: Bruderschaft . “It means a band of brothers — and sisters, too,” she said.

It was at that moment that they looked up and saw three men in uniform come across the bridge — and with them was the minister of culture. His silver hair was disheveled and his face pale. Two of the men were in the light blue uniform of the Berganian police and one — who walked in front with a swagger — wore khaki with a swastika on the sleeve. It was this man who marched up to Magda and the teacher with whom she was playing chess and said sharply, “Where are the German children? Which tent?”

The teacher stood up and looked about him. “They are everywhere,” he said, startled by the sudden command.

And indeed they were. Some were playing football with Matteo. A little girl with a crown of flaxen pigtails, her arm around her new friend from Portugal, was sitting on the steps of the platform listening to the music.

“Call them at once,” barked the Nazi officer. “Get them together. Why are they not in an orderly group?”

The teacher looked bewildered. “They have made friends,” he said. “It is—”

“Round them up,” repeated the officer. “They have one hour to get ready. A bus will take them to the station.”

“But—”

“They are leaving. The king of Bergania has again insulted the people of Germany and no child of the Fatherland will remain in this country. Hurry!”

The minister of culture had taken Magda aside.

“A directive has come from the Gestapo in Berlin,” he said hurriedly. “I’ve tried to make them listen but it’s impossible.”

On the platform the music ceased; the dancers came to rest. The sudden silence was ominous. The two policemen stood by, looking embarrassed. Gradually, as they understood what was happening, the German children, one by one, came toward their tent. At the same time the other children, in every language, expressed their indignation.

Читать дальше