John Werge - The Evolution of Photography

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Werge - The Evolution of Photography» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: visual_arts, foreign_home, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Evolution of Photography

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Evolution of Photography: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Evolution of Photography»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Evolution of Photography — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Evolution of Photography», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The realization of his hopes was more accidental than inferential. The compounds with which he worked, neither produced a visible nor a latent image capable of being developed with any of the chemicals with which he was experimenting. At last accident rendered him more service than reasoning, and occult properties produced the effect his mental and inductive faculties failed to accomplish; and here we observe the great difference between the two successful discoverers, Reade and Daguerre. At this stage of the discovery I ignore Talbot’s claim in toto . Reade arrived at his results by reasoning, experiment, observation, and judiciously weakening and controlling the re-agent he commenced his researches with. He had the infinite pleasure and disappointment of seeing his first picture flash into existence, and disappear again almost instantly, but in that instant he saw the cause of his success and failure, and his inductive reasoning reduced his failure to success; whereas Daguerre found his result, was puzzled, and utterly at a loss to account for it, and it was only by a process of blind-man’s bluff in his chemical cupboard that he laid his hands on the precious pot of mercury that produced the visible image.

That was a discovery, it is true; but a bungling one, at best. Daguerre only worked intelligently with one-half of the elements of success; the other was thrust in his way, and the most essential part of his achievement was a triumphant accident. Daguerre did half the work—or, rather, one-third—light did the second part, and chance performed the rest, so that Daguerre’s share of the honour was only one-third. Reade did two-thirds of the process, the first and third, intelligently; therefore to him alone is due the honour of discovering practical photography. His was a successful application of known properties, equal to an invention; Daguerre’s was an accidental result arising from unknown causes and effects, and consequently a discovery of the lowest order. To England, then, and not to France, is the world indebted for the discovery of photography, and in the order of its earliest, greatest, and most successful discoverers and advancers, I place the Rev. J. B. Reade first and highest.

SECOND PERIOD. DAGUERREOTYPE

SECOND PERIOD

PUBLICITY AND PROGRESS

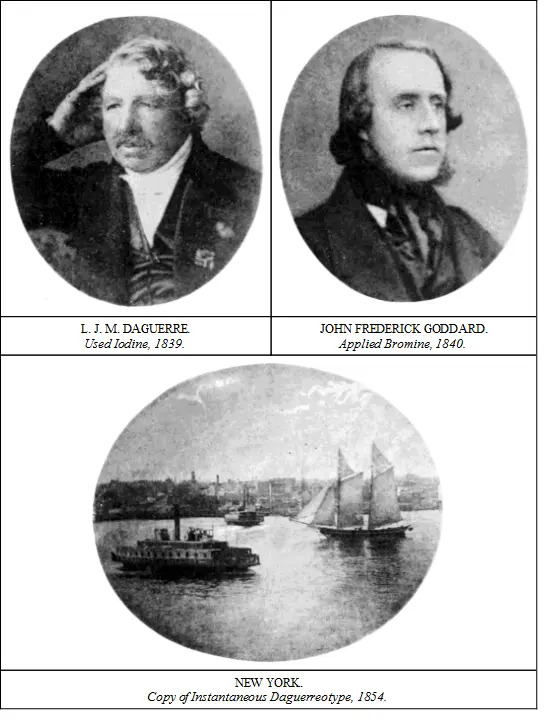

1839 has generally been accepted as the year of the birth of Practical Photography, but that may now be considered an error. It was, however, the Year of Publicity, and the progress that followed with such marvellous rapidity may be freely received as an adversely eloquent comment on the principles of secrecy and restriction, in any art or science, like photography, which requires the varied suggestions of numerous minds and many years of experiment in different directions before it can be brought to a state of workable certainty and artistic and commercial applicability. Had Reade concealed his success and the nature of his accelerator, Talbot might have been bungling on with modifications of the experiments of Wedgwood and Davy to this day; and had Daguerre not sold the secret of his iodine vapour as a sensitiser, and his accidentally discovered property of mercury as a developer, he might never have got beyond the vapoury images he produced. As it was, Daguerre did little or nothing to improve his process and make it yield the extremely vigorous and beautiful results it did in after years. As in Mr. Reade’s case with the Calotype process, Daguerre threw the ball and others caught it. Daguerre’s advertised improvements of his process were lamentable failures and roundabout ways to obtain sensitive amalgams—exceedingly ingenious, but excessively bungling and impractical. To make the plates more sensitive to light, and, as Daguerre said, obtain pictures of objects in motion and animated scenes, he suggested that the silver plate should first be cleaned and polished in the usual way, then to deposit successively layers of mercury, and gold, and platinum. But the process was so tedious, unworkable, and unsatisfactory, no one ever attempted to employ it either commercially or scientifically. In publishing his first process, with its working details, Daguerre appears to have surrendered all that he knew, and to have been incapable of carrying his discovery to a higher degree of advancement. Without Mr. Goddard’s bromine accelerator and M. Fizeau’s chloride of gold fixer and invigorator, the Daguerreotype would never have been either a commercial success or a permanent production.

1840 was almost as important a period in the annals of photography as the year of its enunciation, and to the two valuable improvements and one interesting importation, the Daguerreotype process was indebted for its success all over the world; and photography, even as it is practised now, is probably indebted for its present state of advancement to Mr. John Frederick Goddard, who applied bromine, as an accelerator, to the Daguerreotype process this year. In the early part of the Daguerreotype period it was so insensitive there was very little prospect of being able to take portraits with it through a lens. To meet this difficulty Mr. Wolcott, an American optician, constructed a reflecting camera and brought it to London. It was an ingenious contrivance, but did not fully answer the expectations of the inventor. It certainly did not require such a long exposure with this camera as when the rays from the image or sitter passed through a lens; but, as the sensitised plate was placed between the sitter and the reflector, the picture was necessarily small, and neither very sharp nor satisfactory. This was a mechanical contrivance to shorten the time of exposure, which partially succeeded, but it was chemistry, and not mechanics, that effected the desirable result. Both Mr. Goddard and M. Antoine F. J. Claudet, of London, employed chlorine as a means of increasing the sensitiveness of the iodised silver plate, but it was not sufficiently accelerative to meet the requirements of the Daguerreotype process. Subsequently Mr. Goddard discovered that the vapour of bromine, added to that of iodine, imparted an extraordinary degree of sensitiveness to the prepared plate, and reduced the time of sitting from minutes to seconds. The addition of the fumes of bromine to those of iodine formed a compound of bromo-iodide of silver on the surface of the Daguerreotype plate, and not only increased the sensitiveness, but added to the strength and beauty of the resulting picture, and M. Fizeau’s method of precipitating a film of gold over the whole surface of the plate still further increased the brilliancy of the picture and ensured its permanency. I have many Daguerreotypes in my possession now that were made over forty years ago, and they are as brilliant and perfect as they were on the day they were taken. I fear no one can say the same for any of Fox Talbot’s early prints, or even more recent examples of silver printing.

Another important event of this year was the importation of the first photographic lens, camera, &c., into England. These articles were brought from Paris by Sir Hussey Vivian, present M.P. for Glamorganshire (1889). It was the first lot of such articles that the Custom House officers had seen, and they were at a loss to know how to classify it. Finally they passed it under the general head of Optical Instruments. Sir Hussey told me this, himself, several years before he was made a baronet. What changes fifty years have wrought even in the duties of Custom House officers, for the imports and exports of photographic apparatus and materials must now amount to many thousands per annum!

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Evolution of Photography»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Evolution of Photography» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Evolution of Photography» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.