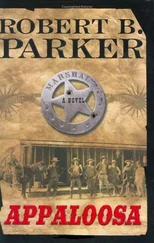

“Don’t seem right,” Virgil said. “He can just take everything they got.”

“No,” I said. “It don’t.”

“Don’t seem like it would be legal,” Virgil said.

“Don’t matter none,” I said. “Legal, illegal. There’s not any law around here anyway.”

“’Cept us,” Virgil said.

“What do we do when Wolfson tells us to move them off the land?” I said.

“Been thinking on that,” Virgil said.

He kept looking at the skeletal remnants of the two Indians.

“Can’t keep taking a man’s money,” Virgil said finally, “and keep saying no to what he wants you to do.”

“I know,” I said.

“Can’t run them people off their land,” Virgil said.

“I know,” I said.

Virgil and I were on the front porch of the Blackfoot, admiring the early evening, when Beth Redmond came down the street with her skirts tucked up, astride one of those nondescript, big-boned horses that a lot of sodbusters had, because they could afford only one. When she reached us she held her skirts down and swung her left leg over the horse and slid modestly off him on the side away from us. Then she came around, hitched the horse, and came up on the porch and sat on the railing opposite us with her feet dangling.

“Evenin’, Beth,” Virgil said.

“Hello,” she said. “Hello, Mr. Hitch.”

I nodded toward her.

“Mrs. Redmond.”

“Virgil, we have to talk,” she said.

“Talk in front of Everett,” Virgil said. “I’d just tell him later anyway.”

“He knows about us?” she said.

“Yep.”

“That’s a little embarrassing,” she said.

“Everett don’t care,” Virgil said.

“But I might,” she said.

“Suppose you might,” Virgil said. “Hadn’t thought of that.”

I stood.

“I can go,” I said.

She shook her head rapidly.

“No,” she said. “Stay. What I’m talking about will include you, too.”

I sat.

“We ain’t going to leave,” she said.

“You and Redmond?” Virgil said.

“None of us,” she said. “Mr. Stark’s going to help us rebuild. He’ll give us the lumber on credit. He’ll give some of the men jobs in the lumber camp.”

“Wolfson already put up signs on the land,” I said. “He says it’s his now.”

“We won’t let him take it,” Mrs. Redmond said.

Neither Virgil nor I said anything.

“Since the Indians,” she said, “when we were all together, and armed, and ready. The men feel like they won, and can win again.”

“Mrs. Redmond,” I said. “They didn’t see an Indian.”

“Please call me Beth,” she said. “I know. But they were ready, and it makes them feel better. And Mr. Stark is making them feel better. They ain’t felt good for an awful long time. They need to do this.”

I nodded. Virgil nodded.

“Stark gonna help you when the guns come?” Virgil said.

“He said he would.”

“Bunch of lumberjacks,” Virgil said.

“They’re tough men,” she said.

“With a peavey,” Virgil said. “Guns are a little different.”

“I know,” Beth said. “But we ain’t gonna go.”

“How ’bout you and your husband,” Virgil said.

“It’s the same thing as the rest,” Beth said. “When we was all here, and the Indians was coming, and everybody had a gun, he felt like he was protecting me and the kids. He felt like he was the leader of his friends. He felt good.”

“He know ’bout us?” Virgil said.

“Yes.”

“How’s he feel ’bout that?” Virgil said.

“He thinks he deserved it,” Beth said. “For beating me up and everything. Swears that he’s a changed man now. Swears that he’ll never hit me again.”

I knew Virgil would not ask, so I did.

“You and him back together, then?” I said.

“Yes.”

She looked sideways at Virgil. Virgil nodded.

“I’m sorry, Virgil,” she said. “You’ve been a good friend.”

“Perfectly fine,” Virgil said.

No one spoke. The nondescript plow horse was scratching the underside of his jaw on the hitching rail. We all watched him.

Then Virgil said, “You got something else, Beth.”

She nodded.

“I…” She stopped and then tried again. “I…”

She stopped and looked wordlessly at Virgil.

“You want us to help you,” Virgil said.

“Help him,” she said. “Help the men. Don’t run them off, no matter what Wolfson says.”

Virgil nodded.

“Can you do that for me?” Beth said.

Virgil didn’t speak for a while. I waited. Beth waited.

Then he said, “I won’t run them off.”

Beth looked at me.

“Mr. Hitch?”

“Everett,” I said.

“Will you run them off, Everett?” she said.

“No,” I said. “I’m with Virgil.”

“What about the other two,” she said.

Now that it was out, she was emptying the pitcher.

“I’ll talk to them,” Virgil said.

“Will they listen to you?”

“Yes,” Virgil said.

“And Mr. Wolfson, what will he do?” she said.

“Hire other people,” Virgil said.

“And what will you do then?” Beth said.

It was out, and we were all looking at it. None of us said anything for a time.

Finally, Virgil said, “Step at a time, Beth. Step at a time.”

Wolfson got ahead of us. He came back from his travels with a big-bodied, dark-haired man named Major Lujack.

“Major Lujack is the head of Lujack Detective Agency in Wichita,” Wolfson said. “And a retired Cavalry officer.”

“Battle of Muddy River?” I said.

Lujack looked at me and nodded.

“You’ve heard of Major Lujack?” Wolfson said.

“Slaughtered a camp full of Comanche women and children, ” I said. “In eastern Colorado. While back. Got a medal for it, and was discharged two weeks later.”

“Everett’s retired Army, too,” Virgil said.

“It was an honorable discharge,” Lujack said.

“Army covered it up,” I said. “Made it sound like a battle. But they got rid of you.”

“Who’s this?” Virgil said.

He was looking at a willowy, round-faced, sloe-eyed man with a flat crowned hat and striped pants, who was standing next to Lujack.

“My assistant,” Lujack said. “Mr. Swann.”

“I’m Mr. Cole,” Virgil said. “This is Mr. Hitch.”

Swann nodded.

“Major Lujack is here to help us with the settlers and all,” Wolfson said. “The rest of his people will be arriving soon.”

Both Lujack and Swann wore guns. They seemed comfortable with them.

“How many,” Virgil said.

“Three squads of five men and a squad leader,” Lujack said.

“Plus you and Mr. Swann,” Virgil said. “So twenty.”

“Yes,” Lujack said.

Virgil was looking at Swann. Swann was looking back at Virgil.

“You fellas have had a long ride,” Wolfson said. “Lemme show you your rooms.”

“Certainly,” Lujack said.

He looked at me. Swann looked hard at Virgil. Then they turned and followed Wolfson.

“Whaddya know about Lujack?” Virgil said.

“He’s a butcher,” I said.

“Why’d he do it?”

“Don’t know,” I said. “Don’t know why he even attacked them. There wasn’t a warrior within fifty miles.”

“And the Army gave him the boot?”

“Yeah. Some of his command had refused to keep up the killing once they realized they weren’t fighting men. Afterwards, he was in the process of court-martialing them.”

“Insubordination?” Virgil said.

I grinned.

“Desertion,” I said. “In the face of the enemy.”

“Even the Army couldn’t stomach it,” Virgil said.

Читать дальше