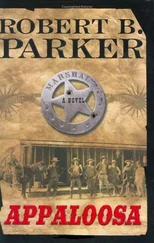

“Don’t let them move us,” Redmond shouted, and tried to step around Virgil. Virgil herded him with his horse, like he was cutting out a steer.

“Hold it,” Redmond shouted. “Hold it or we’ll start shooting.”

“No,” Ward screamed. “No. I don’t want the fucking property.”

Virgil stopped his horse and sat still. The rest of us did the same.

“I can’t live like this,” Ward said. “I can’t live here waiting for the next shootout. I’m a rancher. I don’t want this.”

No one moved.

Then Redmond said, “Stan, if we don’t stop him here, where will we stop him?”

“Don’t care,” Ward said. “Stop him without me. Ranch is yours, Wolfson. I’ll take the horses, the wagon, and whatever we can load on it. Rest is yours.”

“Wise choice,” Wolfson said. “We’ll wait.”

Slowly, watching Redmond as he did, Virgil backed his horse up. The rest of us did the same. Redmond half-raised his Winchester. Virgil had no reaction. The hammer was down on the Winchester. Meant that Redmond would either have to work the lever or cock it, and that, for Virgil, was an ocean of time.

“Disagreement’s been revolved,” Virgil said. “Time to go home.”

The man in the straw hat said to Ward, “Need a hand with the wagon?”

Ward nodded.

“’Preciate it, Saul,” he said.

They turned and went toward the house. Some of the others went with them; the rest began to drift toward their horses.

“It’ll happen to one of us next, and then another one,” Redmond said in a high voice, “and another one, until he’s got it all.”

The rancher in the blue striped shirt paused near his horse. He was carrying his Winchester with the barrel pointing toward the ground.

He said to Redmond, “We ain’t gunmen, Bob.”

Then he swung up into the saddle and rode away.

Virgil and I were leaning on the bar, watching the smoke swirl and the whiskey pour and the cards slap down on tabletops.

“Spent a lot of my life in saloons like this,” Virgil said.

“I know,” I said.

“Funny thing is, neither one of us drinks much.”

“Probably a good thing,” I said.

“Probably,” Virgil said.

He looked comfortably around, appearing to pay no attention, in fact seeing everything.

“I been reading a book by this guy Russo,” Virgil said.

“Who?”

“French guy, Russo. Wrote something called The Social Contract, lot of stuff about nature.”

“Rousseau,” I said.

“Yeah, him,” Virgil said.

Virgil never admitted to a mistake. But if he was corrected, he never made it again.

“He says that men are good, and what makes them bad is government and law and stuff.”

“Don’t know much about Rousseau,” I said.

“Didn’t teach you ’bout him?” Virgil said. “At the Point?”

“Nope. Spent a lot of time on Roman cavalry tactics,” I said. “Not so much on French philosophers.”

“That what he was?” Virgil said. “A philosopher?”

“I think so,” I said.

“Well, he says if people was just left to grow up natural, they’d be good,” Virgil said. “You think that’s so?”

“Don’t know,” I said. “And I ain’t so sure it matters.”

Virgil nodded.

“’Cause nobody ever grew up that way,” he said.

I nodded.

“And probably ain’t going to,” Virgil said.

I nodded again.

“So what difference does it make?” I said.

“I dunno,” Virgil said. “I like reading about it. I like to learn stuff.”

“Sure,” I said.

“And if this Rousseau is right, then the law ain’t a good thing, that protects people; it’s a bad thing that, like, makes them bad.”

“Ain’t much law here,” I said.

“’Cept us,” Virgil said.

I laughed.

“’Cept us,” I said.

Virgil grinned.

“And Cato and Rose,” he said.

We both laughed.

“There’s some law for you,” I said.

“And it don’t much come from no government,” Virgil said, “or any, you know, contract or nothing.”

“Nope,” I said.

“Comes ’cause we can shoot better than other people.”

“And ain’t afraid to,” I said.

Wolfson came across the room and stopped in front of us.

“Virgil,” he said. “I got something to say.”

Virgil nodded.

“I mean alone,” Wolfson said.

“Go ahead and talk in front of Everett,” Virgil said. “Save me the trouble of telling him what you said.”

Wolfson didn’t like it, but Virgil showed no sign that he cared.

“I didn’t appreciate you telling people not to shoot Redmond, ” Wolfson said.

“You wanted him shot?” Virgil said.

“I want to decide those things, not you.”

“Don’t blame you,” Virgil said. “But you ain’t doing the shooting.”

Wolfson frowned.

“I don’t get you, Cole,” he said. “I’d expect that you’d want him dead.”

“Why’s that?”

“Well,” Wolfson said, “I mean, you’re fucking his wife.”

Virgil stared at Wolfson and said nothing.

“Well, I mean, no offense,” Wolfson said.

Virgil stared silently.

“Damn it, Cole, you work for me, don’t you?” Wolfson said. “You act like you’re in charge of everything. Like you don’t work for anybody.”

Virgil shrugged. Wolfson looked at me.

“You too, Everett,” he said. “You act like a couple fucking English kings, you know? Like you can do what you want.”

“And Cato and Rose ain’t much better,” I said.

“No, goddamn it, they ain’t,” Wolfson said.

“You ever read Rousseau?” Virgil said.

“I don’t read shit,” Wolfson said. “Including Roo whatever his fucking name is.”

“Nope,” Virgil said. “’Spect you haven’t.”

He turned and spoke to Patrick.

“I’d like just a finger of whiskey,” he said.

Patrick poured some, and a shot for me as well. He held the bottle up toward Wolfson, and Wolfson shook his head.

“Things gonna have to change around here,” he said, and turned and walked away.

“Things gonna change,” he muttered as he walked. “Things gonna fucking change.”

“Why doesn’t he fire us?” I said.

“He’s scared of us,” Virgil said.

“And Cato and Rose,” I said.

“Same thing,” he said.

“So what do you think he’ll do?”

“Hire himself enough people to back him,” Virgil said. “Then he’ll feel safe. Then he’ll fire us.”

“You and me.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Cato and Rose?”

“Uh-huh.”

We sipped our whiskey.

After a while I said to Virgil, “Is it true?”

“What?”

“What he said. You poking Mrs. Redmond?”

“Ain’t gentlemanly to tell,” Virgil said.

I nodded.

“Hell, it ain’t even too gentlemanly to ask,” Virgil said.

“You are,” I said.

Virgil shrugged.

“Well,” I said, “ain’t you some kind of dandy.”

“Always have been,” Virgil said.

The next time we took Mrs. Redmond out to the ranch, Redmond came out of the house with the children and Mrs. Redmond climbed down from the buggy and went and sat on the porch with them while we sat our horses up the slope a ways.

“You pay any of Wolfson’s whores, Everett?” Frank Rose said.

I nodded.

“They’re all Wolfson’s whores,” I said.

“He says we can use anyone we want, no charge,” Rose said. “And a whore wants to give it to me for nothing, I’ll take it, and so will Cato. But me and Cato, we figure it ain’t Wolfson’s to say, you know? I mean, he don’t quite own ’em. Unless we pay them when they fuck us, they’re getting nothing.”

Читать дальше