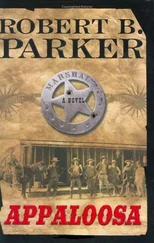

“If it is I’ll add it to Blackfoot,” Wolfson said.

“What if the miners object?” I said.

Wolfson shrugged.

“How ’bout Stark?” I said. “Think he’ll give you trouble.”

Wolfson grinned, his loose eye wandering as he spoke.

“He won’t like it when I take his lumber business,” Wolfson said.

“Him, too?” I said.

“I’m going to own everything in this town,” Wolfson said. “Simple as that.”

“Ranches, too?” I said.

“Ranches,” Wolfson said, “lumber, mining, bank, general store, saloons, hotel, everything.”

Virgil was looking at Wolfson thoughtfully.

“We just shot hell out of your army,” he said to Wolfson.

“Which means if I hired you four boys to help me with this,” Wolfson said, “we should be pretty successful.”

“What would we be doing when we weren’t shooting ranchers and miners and lumberjacks?” Rose said.

“You could pretty much intimidate all those people,” Wolfson said. “Don’t know you’d have to do much shootin’.”

“Fine,” Rose said. “So what would we do otherwise?”

“Keep order,” Wolfson said. “There’s no law in this town. You boys could be like the law. Like Everett was in here.”

“’Cept we wouldn’t be the law,” Virgil said.

“Be the same,” Wolfson said. “’Fore you boys came here. Everett had this place turned into a damn refuge, you know? People got in trouble anywhere in town, they run here, to Everett.”

“But you wasn’t the law,” Virgil said.

“Just in here,” I said.

“Hell.” Wolfson drank some more whiskey. “We be running things on this whole side of the mountain. You want laws, I’ll write up some laws. You boys want to be lawmen, I’ll make you lawmen.”

“Just you,” Virgil said.

“Boys, a town’s got a right to appoint lawmen,” Wolfson said. “And right now, I’m the town.”

Virgil got up and walked to the saloon door and looked out at the silent street, lit by a full moon.

“Bodies are gone,” he said.

“Chinamen,” Wolfson said. “Take everything valuable and dump what’s left outside of town. Animals eat ’em pretty clean in a couple days.”

Virgil nodded slowly, staring out at the street.

“So we got a deal?” Wolfson said. “Pay you top wages.”

Cato looked at Rose. I looked at both of them. None of us said anything. We all looked at Virgil, who was still staring out into the street.

Then Cato said, “What you think, Virgil?”

Virgil was silent for a moment, then, without looking back, he said, “Gotta think on it,” and walked out into the moonlight.

We could head for Texas,” I said to Virgil.

“We could,” Virgil said.

“I don’t owe Wolfson anything,” I said.

“Nope.”

“You haven’t even taken his money.”

“True,” Virgil said.

“Cato and Rose will probably stay,” I said.

“Probably,” Virgil said.

We were working the horses again. We’d already let them stroll. Then we’d breezed them pretty hard for a while. Now, with the reins looped over the saddle horn, we were letting them browse along, nibbling grass.

“We could head for Texas,” I said.

“Could,” Virgil said.

“Ain’t we just had this talk?” I said.

“Yep.”

“So why don’t we head for Texas,” I said.

“Ain’t time yet,” Virgil said.

“Because?”

Virgil leaned back in his saddle and looked up at an eagle circling slow and easy on the air currents in the sky.

“Don’t want Wolfson running the town,” Virgil said.

“Why not?”

“Same reason we didn’t want that mob lynching Cato and Rose,” Virgil said.

“’Cause it would be against the law?”

Virgil shook his head. The horses moseyed along, reins loose, head down, nosing at the grass.

“I ain’t a lawman,” he said.

“Good thing,” I said. “Ain’t nothing happened here since I got here had anything to do with law.”

“Had to do with us shooting better than them,” Virgil said.

“It did,” I said.

“Better than shootin’ worse,” Virgil said.

There was a stream to the right. In the late summer it would probably be dry. But for now, it came up near the bottom of the hills behind us and found its way down a shallow wash to the bigger stream that ran among the homestead ranches. The horses smelled it and veered over to it and drank from it. Virgil patted his horse’s neck quietly while he drank.

“Don’t feel bad about anything I done here,” I said.

Virgil patted his horse some more. He nodded.

“I know,” he said.

You got any money left?” I said.

“Not much,” Virgil said.

“Me either.”

“Don’t need much,” Virgil said.

“Got to have some,” I said.

“Maybe we should work for Wolfson,” Virgil said. “While we see how things develop.”

“And if they develop wrong?”

“Don’t know about wrong,” Virgil said. “But Wolfson shouldn’t run the whole town.”

“With Cato and Rose to back him.”

“So if it goes that way, we quit?”

“Probably,” Virgil said.

“And do what?” I said.

“Can’t say.”

“Might have to go against Cato and Rose,” I said.

“Might.”

“And you’re willing?”

“Yep.”

“Yesterday you was saving their lives,” I said.

“We was,” Virgil said.

“What’s the difference?”

“Don’t know,” Virgil said. “Maybe we’ll find out.” We picked up our reins and lifted the horses’ heads and pointed them back toward town.

“Virgil,” I said as the horses walked toward home, “I get killed while you figure out what you are, I’m gonna resent it.”

Virgil nodded.

“Don’t blame you,” he said.

So we were all working for Wolfson. Me and Virgil doing lookout duty at the Blackfoot. Cato and Rose doing the same at the Excelsior. It was a lot more firepower than either saloon needed. And we all knew it. But we also all knew that keeping order in a couple of saloons was not why Wolfson paid us. It was just something useful to do while we waited.

On a wet Tuesday morning Virgil and I, with our hats pulled down and our collars turned up, rode through the hard rain, up to the copper mine with Wolfson.

“We couldn’t do this tomorrow?” I said to Wolfson.

“Decided to do it today,” Wolfson said. “Gonna do it today. When I do business, I do business.”

Wolfson looked sort of funny on horseback, out in the daylight. He had on a black slicker and a big hat, and seemed out of place.

“Fine,” I said.

Virgil said nothing. I knew he could barely tolerate Wolfson.

At the mine we put the horses under a tarpaulin shelter beside the mine shack and went on and had some coffee with the mine foreman, a tall, stoop-shouldered guy with a lot of gray beard. His name, he said, was Faison.

“Sorry about the trouble up here last week,” Wolfson said. “I hope no miners were hurt.”

“Nope, we stayed low,” Faison said.

“Smart,” Wolfson said.

“You taking over the mine?” Faison said.

“I’d like to do that,” Wolfson said. “Keep everybody on, promote you to mine manager.”

“More money?” Faison said.

“Of course,” Wolfson said.

Faison nodded.

“Nobody misses O’Malley,” Faison said. “Or the gun hands he brought in, neither.”

He looked at Virgil and me.

“No offense,” he said.

I shook my head. Virgil said nothing.

“Only thing anybody misses is payday,” Faison said. “You keep the paydays in order, we’ll be happy to work for you.”

Читать дальше