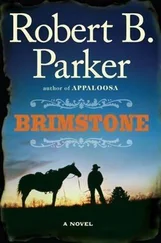

“Everett.”

I turned. It was Virgil coming down the track from the north. I walked toward him in the steady rain. He had his coat collar up and his hat snugged down low. Water was pouring off the brim.

“You see anything?” he said.

“I think he’s in those woods there by the creek, but I don’t know for sure. I found this.”

I handed Virgil the parfleche pouch.

“Not much inside. I felt some cartridges, a whetstone, I think some jerky.”

“As much as that goulash we ate in the Hungarian café at Dallas depot has worn off, I wouldn’t eat that jerky,” Virgil said. “Could be backstrap off his kinfolk.”

I was not able to make out the expression on Virgil’s face, but it was clear by his body language that he was not satisfied with the situation.

“We’re not going in those woods,” Virgil said.

Virgil stood and looked east toward the woods. He called out into the dark, rainy night.

“Bob Brandice! If you do not die in those woods, rest assured I will kill you!”

When we got back to the coach it was still raining hard, maybe even harder since we had left the place where we’d been looking for Bob. I was starting to feel the wet cold in my bones, and I know Virgil was feeling it, too. We had been waterlogged for hours, and I was hungry. I know Virgil was as hungry, too, but he would not say so. If food were an option or if dry and comfortable were an option, he’d cover the option, but there was no need to ponder the possibility of food or staying very dry. Thankfully, though, after we’d traveled for twenty minutes or so the rain started letting up, and we could see a piece of the moon.

“Looks like we might be leaving this rain behind.”

“Does,” Virgil said.

“Won’t bother me none.”

“That’s good,” Virgil said.

We coasted for a bit longer and came to a tight canopy of trees that sheltered us from the sprinkling rain. When we cleared the tunnel of trees we were rolling pretty fast and were clearly on a wide sweep to the west.

“This has got to be the turn Whip was talking about,” I said.

“Hold us up, Everett.”

“What?”

“Slow her up.”

I did as Virgil asked and turned the brake wheel, which made a low grinding noise as we slowed.

Virgil looked at me, cocked his head a bit.

“Smell that?”

I had not caught a whiff, but in the next second, I did.

“Smoke,” I said.

“Let’s stop.”

I stopped the coach, and Virgil stepped off the platform. He walked down the dark track a ways, then stopped and stood still.

“Been plenty of lightning,” I said. “Might be the woods struck up.”

“Might be.”

“Could be a homestead,” I said. “Or Indians.”

The rails in front of us turned and disappeared behind a wall of thick woods.

“Let me walk a bit,” Virgil said. “Just follow me.”

Virgil started walking down the track. I turned the brake wheel, freeing the coach, and very slowly began to roll. After maybe a hundred yards we entered into a tall rocky hillside that had been dynamited for the rails. Virgil was hard to see clearly in the darkness. He was walking about seventy-five feet in front of the coach, and when he got to the edge of the rocky hillside, he held up his arms, motioning for me to stop. I turned the wheel, and the coach started slowing. Virgil remained standing on the track, looking downhill as the coach came to a stop square in the middle of the dynamited hillside. I foot-latched the brake, stepped off the platform, and started down the track toward Virgil. As I got closer, I saw what he saw.

A quarter of a mile down the track was the fire. It was hard to tell exactly what was burning, but whatever it was, rain or no rain, it was burning and the flames were high. In the distance behind the fire and off toward the west a ways, there was a faint glow.

“Half Moon Junction,” I said.

Virgil turned and looked back at me as I walked up.

“Maybe you can tell me for certain,” Virgil said, “but this dead hand here is Woodfin, ain’t it? One of Bragg’s top gun hands. We had a run-in or two with him, did we not?”

I was fixed on the fire and the sight of the town, and I had not noticed the man lying directly in front of Virgil, between the rails.

I looked at the big bearded man with the white shirt covered in blood, and he was for certain who Virgil thought he was.

“That’s him. That’s Woodfin. Vince and him were Bragg’s two backup bulls,” I said. “Lying between the rails like this, he’s obviously not one we shot.”

“No, he ain’t,” Virgil said.

I leaned down a little closer, and when I did I could see under Woodfin’s beard his throat was sliced open across his jawline, from ear to ear.

“Throat cut,” I said.

“Handiwork of Bloody Bob, no doubt,” Virgil said.

“Good of him to do some stall mucking.”

“Is,” Virgil said. “Reckon him and Woodfin had a misunderstanding.”

“Wonder what the outcome of an argument would have been?”

I looked back to Virgil. His attention was now on the distant flames ahead of us.

“That the coaches on fire, you think?” I said.

“Looks like it,” Virgil said. “Hard to say for certain.”

“Figure we’ll know soon enough,” I said.

“Figure we will.”

“And Half Moon, just there.”

“That it is,” Virgil said.

We left the coach where it had stopped and walked on down the track toward the fire. With the recently slain bandits, Virgil and me had plenty of weaponry choices. I carried my Colt and two other long-barreled Colts. Virgil had the .44 Henry rifle Bob dropped in the aisle and a second Colt in his belt.

“Least with Bob shot up, gone, hopefully dead,” I said, “and Woodfin cut like that, we have two less gunmen to deal with.”

“We do,” Virgil said.

“Vince is shot up, too,” I said. “No telling how bad, how deep. Might be he’s dead.”

“Might well be,” Virgil said.

“Ear shots are damn sure painful.”

“They are.”

“Hard to stop the bleeding,” I said, “and the pressure on the brain.”

“Don’t know he’s even got one.”

“Well, if he don’t bleed to death,” I said, “he’ll most likely go crazier than he already is.”

We continued walking, following the track toward the fire ahead and the halo of light from Half Moon Junction just beyond. There was no more rain now, and the moon was showing full in the sky as we made our way closer to the fire.

“That’s the coaches burning for sure,” I said.

“It is,” Virgil said.

As we got closer we could see the fire was a single coach engulfed in flames, but the wood was nearly consumed and the flames were getting lower.

“The governor’s car,” I said. “The Pullman.”

“Is,” Virgil said.

“Let’s hope him and his wife are not inside,” I said.

“Yep,” Virgil said. “Let’s.”

As we got closer we could see the other cars were safe.

“The Pullman’s separated from the cars behind,” Virgil said.

The other coaches were disconnected from the burning Pullman and were sitting fifty or so feet farther down the rail.

“Must have been disconnected on the move,” I said.

Avoiding any possibility of being spotted by anyone, we skirted off the tracks, moved into the trees, and continued on closer to the burning Pullman and back section of the train. As we neared the coaches we could see there were lamps burning in the fifth and sixth car and the caboose, but there was no one moving about. We stopped, staying out of sight in the woods when we were parallel with the coaches. Even though the windows were fogged over, there was no movement inside the fifth and six coaches.

Читать дальше