“Take this one as well,” he said. He was out of breath.

“Another book,” I said.

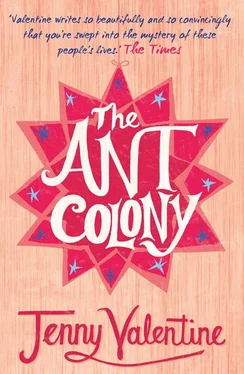

“ The Ant Colony ,” he said, in a voice like you hear at the cinema. “By Dr Bernard O Hopkins.”

I laughed. “Thanks Max.”

“It’s brilliant,” he said, looking at the book and not at me. “A real page turner.”

It was so like Max to talk about an ant book like that, like it was a thriller or something.

I said, “I won’t be able to put it down.”

He nodded, like that was the right answer, and he stood in the orange light of the doorway and watched me walk to the car.

On the drive home Mum and I talked about the books Max had given me. “Ants?” she said. “What a surprise.” Because Max was obsessed with them, how organised they were, how many of them there might be, how they all worked together like one animal. Max told me a long time ago that looking down at them made him think he was a giant towering over the earth.

Ants were what we did when we were seven and eight and nine. It was all Max wanted to do. I was like the genius professor’s assistant or something. We dug and photographed and measured. We tracked and timed and watched. We collected them in bottles. Max pickled specimens in vinegar and kept them in the garden shed. He’d forget where we were and who I was even, and everything was just about the ants.

When we got older, and everyone wanted to play football and drive cars on the common and get wrecked and show off down the river to girls, Max was still into ants. There wasn’t a cure for his ant thing.

I showed Mum the other book. I said, “Do you think the life on other planets idea comes from watching ants?”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, ants are kind of weird, like from outer space, and Max has told me before he thinks humans are just like ants, even less if you put them in the context of the universe,”

“Very scientific.” Mum was smiling at me. “Some of his brain cells are rubbing off.”

“Leave it out, Mum,” I said.

She said, “I get vertigo just thinking about life on this planet, never mind scouting around somewhere else for more.”

We started inventing intergalactic package holidays, imagining a time when everybody had got bored of space travel because it was too easy, because everyone was doing it, because it was just not cool. I said Max might find someone nearer his IQ on planet Zargon.

Mum said, “What planet is he going to find his people skills on?”

She said this because Max is one of those clever people who are also about the shyest, most awkward you could meet. Often this can be mistaken for just rude.

“He was talking to you,” I said to Mum. “That’s a start isn’t it?”

“When was he talking to me?” she said.

“Today, in the car, about the book.”

“No,” she said, “he was talking to you.”

I smiled at Mum. “He was talking to you . He was looking at me.”

“See?” she said. “People skills. How do you know that anyway?”

“I know Max,” I said. “Haven’t I known him all my life?”

I told her that in school Max was different, in class anyway. In class Max didn’t speak in sentences – he spoke in whole paragraphs.

“Well, not to me he doesn’t,” Mum said. “I’m lucky if I get one syllable.”

I said, “Some people think one syllable is enough. Like Max’s Mum. She hardly talks to me.”

“Don’t get me started on that woman,” Mum said. “God knows what she’s got against you. I’ve no idea.”

“Whatever,” I said, and I looked out of the window at the rain and thought about something else. Like Rosie, this girl at school I was trying to impress. And Mr Hanlan, the Geography teacher who should’ve been a prison officer, and whether he’d notice I copied Max’s homework, and what he would do if he did. And what I was going to eat when I got home because I was starving.

I watched myself in that car, my head leaning against the water-beaded window, my mind on a lot of nothing. I watched from where I was sitting in a room in Camden with black floorboards, and I thought, if you knew when your life was about to start going wrong, would you change it before it was too late?

The old lady with the dog was called Isabel. She seemed all right to me. Mum told me to watch out cos people like that were never nice for nothing. I was watching out, but I was just walking past her door when she said, “Come on in, whoever you are.”

It was like walking past a phone box when it rings. I’ve always wanted to do that. And then for the phone call to actually be for me.

She was in the kitchen. She said, “Help me get the lid off this bloody yoghurt. Damn stuff is supposed to be good for you and the stress of it is going to finish me.”

She had the pliers out and everything. She’d been trying to pull off the side of the pot cos she couldn’t see where the lid started. I flipped it open in about three seconds. First she looked angry with it and then she laughed.

“I’m Isabel,” she said. “I saw your nice door sticker. Is your name Cherry or Bohemia?”

“Bohemia.”

“Where did you get a name like that?” she said.

I shrugged. “Most people just call me Bo.”

“Well, it’s not a piece of fruit at least,” she said, sort of under her breath so I wouldn’t hear it, except I did. “Cherry your mum’s real name, is it?”

“I think so,” I said, because I’d never been asked that question before.

“Cherry Chapstick?”

“No, Cherry Hoban,” I said.

She started spooning yoghurt into a mug. I was looking at it so she asked me if I wanted some and handed me the rest of the pot. She asked me how old I was and I told her I was ten.

“Why aren’t you at school, Bohemia Hoban?” she said.

I liked that she used my whole name. It made me feel like somebody important. I said I was home-schooled cos that’s what Mum says.

Isabel put her hands on her hips then and clucked her tongue and said, “What lesson is it now then?”

“Yoghurt opening,” I told her, and she laughed.

She said being home-schooled was a lot more than wandering about the place waiting for my mum to wake up.

“She is awake,’ I said, which was actually true.

She said, “If your mum got a whiff of what home-school was about you’d be down the local primary in a second. Home-skiving’s what you’re doing.”

See? That’s why Mum didn’t like Isabel.

I didn’t look at her, even though I know she was looking at me. I ate some more yoghurt before she could ask for it back.

“So you’ve met us all then,” she said.

“I’ve met you and the landlord with the face.”

“That’s Steve,” she said. “Don’t stare. It was an accident with a facial peel.”

I asked her what one of those was and then I wished I hadn’t because it was something to do with burning your old skin off with acid.

I gave her back the yoghurt. “Why would someone want to do that?” I said.

She told me not to underestimate the power of getting old, or something. “Ask your mum,” she said. “Watch her closely when she hits forty.”

I asked her who else there was to meet.

“Well, you’ve got Mick to come – beard, bike, body odour. Met him yet?”

“Nope.”

“Aren’t you the lucky one.” She looked at her ceiling. “The flat above me’s empty, but it won’t be for long.”

“What about your dog?” I said, and I asked her what it was called.

“Doormat,” she said. “Where is he?”

I laughed. “Doormat,” I said after her. “I don’t know where he is, I haven’t seen him. Only that time when he was peeing.”

Читать дальше