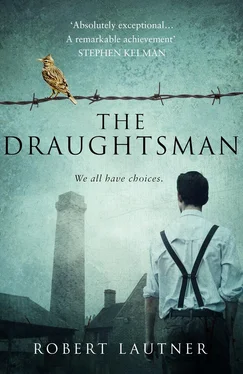

THE DRAUGHTSMAN

Robert Lautner

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on

historical events and figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by HarperCollins Publishers 2017

Robert Lautner asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollins Publishers 2017

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2018

Cover images © Mark Owen/Trevillion Images (figure); www.Shutterstock.com(all other images)

Every effort has been made to trace and contact copyright holders. If there are any inadvertent omissions we apologise to those concerned and will undertake to include suitable acknowledgements in all future editions.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780008126711

Ebook Edition © January 2017 ISBN: 9780008126735

Version: 2018-01-09

‘It is not so much the kind of person a man is as the kind of situation in which he finds himself that determines how he will act.’

Stanley Milgram, Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View (1974)

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Prologue

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Part Two

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Part Three

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Part Four

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Robert Lautner

About the Publisher

Erfurt, Germany,

February 2011

The site had become a squat for the disenfranchised, for anarchic youth. They even formed a cultural group. Artists and rebels. Appropriate. Perhaps.

Over the bridge, across the railway that once moved the iron goods from the factory to the camp at Buchenwald, Erfurt still maintained its tourist heart, its picture-book heart. A place where romance comes. Where carriages drawn by white horses still mingle with trams and buses and young and old marrieds hold hands crossing the market square. Rightly fitting, just so, that the industrial quarter on Sorbenweg ignored, left to rot, to be forgotten. A despised relative a hurt family no longer calls upon. Its only colour in the graffiti, signs and spray-paint portraits that only the youth understood.

The squatters removed, the land and remaining dying buildings reimagined. Erfurt ready to remember that history, no matter its shade, had something to pass on.

Myra Konns ran the morning tours of the museum risen from the ruins of the Topf administration buildings. She guided school-children through the original ISIS drafting tables they had found scattered and vandalised over the years by the transients, guided them through the director’s rooms still furnished with the wide cabinets that once held drafts for cremation ovens. Labels still sitting in their brass handles. The impression of ink soft and leaving. The drawers empty. Yawning only dust and memory. All restored now.

Myra would show them the small canisters with the clay plaques that the factory made to store ashes to be collected by relatives; a legal requirement until someone decided that it was no longer required. Hundreds of them found abandoned and empty in an attic in Buchenwald. These and other smaller items all on the third floor, where the drafting tables were repaired and displayed, where the chief designer’s office had been recreated, where the tours could still see from the window to Ettersberg mountain as the draughtsmen at their tables would have done and Myra would point out that the smoke from the Buchenwald ovens could be seen crawling over the mountain all day. All day.

The oven doors, removed from Auschwitz and Buchenwald, the most sombre items of the tour. No need to highlight the prominence of the company plaque set above them. Topf and Sons exhibited now as the ‘Engineers of the Final Solution’. A brochure saying so.

In one display cabinet Myra would put her hand to a drawing of an experimental oven, never employed; for the allies had closed in before its realisation. Beside it a letter from a director to Berlin explaining the function of the new design. And Myra would always choose her words with care.

‘It works on four levels over two floors, one of which is the basement, where the morgue would traditionally be, replaced by the furnace. The deceased would be put in at the top and a series of rollers over grates would convey them to the furnace. The letter confirms the effectiveness of the design at being able to work continuously. Day and night. Reducing the need for coal as the oven was intended to be fuelled by the deceased themselves. Hundreds, possibly thousands of corpses a day. No intention to distinguish one from the other. A machine. An eradication device criminal in nature and design. Thankfully never introduced. The Allies having liberated Auschwitz some months before.’

A hand went up in the midst of the group. Myra took a breath. An old man. Always a sparse group of old men and women dawdling amongst the children. In her induction, just the month before when the museum opened, Myra had been informed to be especially aware of the aged visitors. The air about the place theirs. The tomb of it theirs.

‘Yes, sir?’

‘Excuse me, Fräulein,’ he bowed slightly. White, pomade-brushed hair and grey-blue eyes that smarted from the cold February wind outside, made worse by the radiator warmth of the halls. He wiped his eyes behind his glasses.

‘That correspondence does not refer to the design of the continuous oven. Of that oven.’

Читать дальше