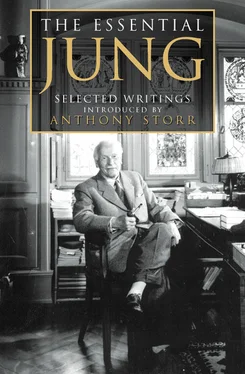

As an example of the kind of observation which led him to this conclusion, Jung quotes a particular case.

From “The Structure of the Psyche” CW 8, pars. 317–21

But as to whether this supra-individual psychic activity actually exists, I have so far given no proof that satisfies all the requirements. I should now like to do this once more in the form of an example. The case is that of a man in his thirties, who was suffering from a paranoid form of schizophrenia. He became ill in his early twenties. He had always presented a strange mixture of intelligence, wrong-headedness, and fantastic ideas. He was an ordinary clerk, employed in a consulate. Evidently as a compensation for his very modest existence he was seized with megalomania and believed himself to be the Saviour. He suffered from frequent hallucinations and was at times very much disturbed. In his quiet periods he was allowed to go unattended in the corridor. One day I came across him there, blinking through the window up at the sun, and moving his head from side to side in a curious manner. He took me by the arm and said he wanted to show me something. He said I must look at the sun with eyes half shut, and then I could see the sun’s phallus. If I moved my head from side to side the sun-phallus would move too, and that was the origin of the wind.

I made this observation about 1906. In the course of the year 1910, when I was engrossed in mythological studies, a book of Dieterich’s came into my hands. It was part of the so-called Paris magic papyrus and was thought by Dieterich to be a liturgy of the Mithraic cult. * It consisted of a series of instructions, invocations, and visions. One of these visions is described in the following words: “And likewise the so-called tube, the origin of the ministering wind. For you will see hanging down from the disc of the sun something that looks like a tube. And towards the regions westward it is as though there were an infinite east wind. But if the other wind should prevail towards the regions of the east, you will in like manner see the vision veering in that direction.” The Greek word for “tube,” means a wind-instrument, and the combination in Homer means “a thick jet of blood.” So evidently a stream of wind is blowing through the tube out of the sun.

The vision of my patient in 1906, and the Greek text first edited in 1910, should be sufficiently far apart to rule out the possibility of cryptomnesia on his side and of thought-transference on mine. The obvious parallelism of the two visions cannot be disputed, though one might object that the similarity is purely fortuitous. In that case we should expect the vision to have no connections with analogous ideas, nor any inner meaning. But this expectation is not fulfilled, for in certain medieval paintings this tube is actually depicted as a sort of hose-pipe reaching down from heaven under the robe of Mary. In it the Holy Ghost flies down in the form of a dove to impregnate the Virgin. As we know from the miracle of Pentecost, the Holy Ghost was originally conceived as a mighty rushing wind, the  , “the wind that bloweth where it listeth.” In a Latin text we read: “Animo descensus per orbem solis tribuitur” (They say that the spirit descends through the disc of the sun). This conception is common to the whole of late classical and medieval philosophy.

, “the wind that bloweth where it listeth.” In a Latin text we read: “Animo descensus per orbem solis tribuitur” (They say that the spirit descends through the disc of the sun). This conception is common to the whole of late classical and medieval philosophy.

I cannot, therefore, discover anything fortuitous in these visions, but simply the revival of possibilities of ideas that have always existed, that can be found again in the most diverse minds and in all epochs, and are therefore not to be mistaken for inherited ideas.

I have purposely gone into the details of this case in order to give you a concrete picture of that deeper psychic activity which I call the collective unconscious. Summing up, I would like to emphasize that we must distinguish three psychic levels: (1) consciousness, (2) the personal unconscious, and (3) the collective unconscious. The personal unconscious consists firstly of all those contents that became unconscious either because they lost their intensity and were forgotten or because consciousness was withdrawn from them (repression), and secondly of contents, some of them sense-impressions, which never had sufficient intensity to reach consciousness but have somehow entered the psyche. The collective unconscious, however, as the ancestral heritage of possibilities of representation, is not individual but common to all men, and perhaps even to all animals, and is the true basis of the individual psyche.

Since the collective unconscious is common to all men, archetypal manifestations can be demonstrated in the normal as well as in the insane.

From “On the Psychology of the Unconscious” Two Essays, CW 7, pars. 106–9

THE PERSONAL AND THE COLLECTIVE UNCONSCIOUS

Let us take as an example one of the greatest thoughts which the nineteenth century brought to birth: the idea of the conservation of energy. Robert Mayer, the real creator of this idea, was a physician, and not a physicist or natural philosopher, for whom the making of such an idea would have been more appropriate. But it is very important to realize that the idea was not, strictly speaking, “made” by Mayer. Nor did it come into being through the fusion of ideas or scientific hypotheses then extant, but grew in its creator like a plant. Mayer wrote about it in the following way to Griesinger, in 1844:

I am far from having hatched out the theory at my writing desk. [He then reports certain physiological observations he had made in 1840 and 1841 as ship’s doctor.] Now, if one wants to be clear on matters of physiology, some knowledge of physical processes is essential, unless one prefers to work at things from the metaphysical side, which I find infinitely disgusting. I therefore held fast to physics and stuck to the subject with such fondness that, although many may laugh at me for this, I paid but little attention to that remote quarter of the globe in which we were, preferring to remain on board where I could work without intermission, and where I passed many an hour as though inspired, the like of which I cannot remember either before or since. Some flashes of thought that passed through me while in the roads of Surabaya were at once assiduously followed up, and in their turn led to fresh subjects. Those times have passed, but the quiet examination of that which then came to the surface in me has taught me that it is a truth, which can not only be subjectively felt, but objectively proved. It remains to be seen whether this can be accomplished by a man so little versed in physics as I am. *

In his book on energetics, † Helm expresses the view that “Robert Mayer’s new idea did not detach itself gradually from the traditional concepts of energy by deeper reflection on them, but belongs to those intuitively apprehended ideas which, arising in other realms of a spiritual nature, as it were take possession of the mind and compel it to reshape the traditional conceptions in their own likeness.”

The question now arises: Whence this new idea that thrusts itself upon consciousness with such elemental force? And whence did it derive the power that could so seize upon consciousness that it completely eclipsed the multitudinous impressions of a first voyage to the tropics? These questions are not so easy to answer. But if we apply our theory here, the explanation can only be this: the idea of energy and its conservation must be a primordial image that was dormant in the collective unconscious. Such a conclusion naturally obliges us to prove that a primordial image of this kind really did exist in the mental history of mankind and was operative through the ages. As a matter of fact, this proof can be produced without much difficulty: the most primitive religions in the most widely separated parts of the earth are founded upon this image. These are the so-called dynamistic religions whose sole and determining thought is that there exists a universal magical power ** about which everything revolves. Tylor, the well-known English investigator, and Frazer likewise, misunderstood this idea as animism. In reality primitives do not mean, by their power-concept, souls or spirits at all, but something which the American investigator Lovejoy has appropriately termed “primitive energetics.” This concept is equivalent to the idea of soul, spirit, God, health, bodily strength, fertility, magic, influence, power, prestige, medicine, as well as certain states of feeling which are characterized by the release of affects. Among certain Polynesians mulungu – this same primitive power-concept – means spirit, soul, daemonism, magic, prestige; and when anything astonishing happens, the people cry out “Mulungu!” This power-concept is also the earliest form of a concept of God among primitives, and is an image which has undergone countless variations in the course of history. In the Old Testament the magic power glows in the burning bush and in the countenance of Moses; in the Gospels it descends with the Holy Ghost in the form of fiery tongues from heaven. In Heraclitus it appears as world energy, as “ever-living fire”; among the Persians it is the fiery glow of “haoma,” divine grace; among the Stoics it is the original heat, the power of fate. Again, in medieval legend it appears as the aura or halo, and it flares up like a flame from the roof of the hut in which the saint lies in ecstasy. In their visions the saints behold the sun of this power, the plenitude of its light. According to the old view, the soul itself is this power; in the idea of the soul’s immortality there is implicit its conservation, and in the Buddhist and primitive notion of metempsychosis – transmigration of souls – is implicit its unlimited changeability together with its constant preservation.

Читать дальше

, “the wind that bloweth where it listeth.” In a Latin text we read: “Animo descensus per orbem solis tribuitur” (They say that the spirit descends through the disc of the sun). This conception is common to the whole of late classical and medieval philosophy.

, “the wind that bloweth where it listeth.” In a Latin text we read: “Animo descensus per orbem solis tribuitur” (They say that the spirit descends through the disc of the sun). This conception is common to the whole of late classical and medieval philosophy.