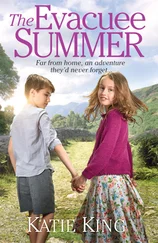

Still, it had only been a couple of days since he had begged Connie to keep quiet on his behalf from now on, following an exceptionally unpleasant few minutes in the boys’ lavatories at school when he had been taunted mercilessly by Larry, one of the biggest pupils in his class, who’d called Jessie a scaredy-cat and then some much worse names for letting his sister speak out for him.

Larry had then started to push Jessie about a bit, although Jessie had quite literally been saved by the bell. It had rung to signal the end of morning playtime and so with a final, well-aimed shove, Larry had screwed his face into a silent snarl to show his reluctance to stop his torment just at that moment, and at last he let Jessie go.

Jessie was left panting softly as he watched an indignant Larry leave, his dull-blond cowlick sticking up just as crossly as Larry was stomping away.

To comfort himself Jessie had remembered for a moment the time his father had spoken to him quietly but with a tremendous sense of purpose, looking deep into Jessie’s eyes and speaking to him with the earnest tone that suggested he could almost be a grown-up. ‘Son, you’re a great lad, and I really mean it. Yer mam an’ Connie know that too, and all three o’ us can’t be wrong, now, can we? And so all you’s got to do now is believe it yerself, and those lads’ll then quit their blatherin’. An’ I promise you – I absolutely promise you – that’ll be all it takes.’

Jessie had peered back at his father with a serious expression. He wanted to believe him, really he did. But it was very difficult and he couldn’t ever seem able to work out quite what he should do or say to make things better.

Back at number five Jubilee Street following the jacks tournament, the twins wolfed down their second tea, egg-in-a-cup with buttered bread this time, and then Barbara told them to have a strip wash to deal with their filthy knees and grime-embedded knuckles.

Although she made sure their ablutions were up to scratch, Barbara was nowhere near as bright and breezy as she usually was.

Even Connie, not as a matter of course massively observant of what her parents were up to, noticed that their mother seemed preoccupied and not as chatty as usual, and so more than once the twins caught the other’s eye and shrugged or nodded almost imperceptibly at one another.

An hour later Connie’s deep breathing from her bed on the other side of the small bedroom the twins shared let Jessie know that his sister had fallen asleep, and Jessie tried to allow his tense muscles to relax enough so that he could rest too, but the scary and dark feeling that was currently softly snarling deep down beneath his ribcage wouldn’t quite be quelled.

He had this feeling a lot of the time, and sometimes it was so bad that he wouldn’t be able to eat his breakfast or his dinner.

However, this particular bedtime Jessie wasn’t quite sure why he felt so strongly like this, as actually he’d had a good day, with none of the lads cornering him or seeming to notice him much (which was fine with Jessie), and the game of jacks ended up being quite fun as he’d been able to make the odd pun that had made everyone laugh when he had come to read out the team names.

As he tried willing himself to sleep – counting sheep never having worked for him – Jessie could hear Ted and Barbara talking downstairs in low voices, and they sounded unusually serious even though Jessie could only hear the hum of their conversation rather than what they were actually saying.

Try as he might, Jessie couldn’t pick out any mention of his own name, and so he guessed that for once his parents weren’t talking about him and how useless he had turned out to be at standing up for himself. He supposed that this was all to the good, and after what seemed like an age he was able to let go of his usual worries so that at long last he could drift off.

Chapter Two

When the children had been smaller, Ted and Big Jessie had met a charismatic firebrand of a left-wing rabble-rouser called David, and eventually he had talked the brothers into going to several political meetings in the East End aimed at convincing the audience of the need for working-class men to band together to form a socialist uprising. A lot of the talk had been of fascists, and the political situation in Spain and Germany.

It wasn’t long before Ted and Big Jessie had been persuaded to go with members of the group to protest against Oswald Mosley’s Blackshirts’ march through Cable Street in Whitechapel, although the brothers had retreated when the mood turned nasty and rocks were pelted about and there were running battles between the left- and right-wing supporters and the police.

Ted, naturally an easy-going sort, hadn’t gone to another meeting of the socialists, and within a few months David had left to go to Spain to fight on the side of the Republicans.

Still, his tolerant nature didn’t mean that Ted would always nod along down at The Jolly Shoreman whenever (and this had been happening quite often in recent months) a patron seven sheets to wind would suggest that any fascist supporters should be strung up high. He didn’t like what fascists believed in but, deep down, Ted believed they were people too, and who really had the right to insist how other people thought?

But in recent weeks Ted had had to think more seriously about what he believed in, and how far he might be prepared to go to protect his beliefs, and his family.

As he was a docker, working alongside Big Jessie on the riverboats that spent a lot of their time moving cargo locally between the various docks and warehouses on either side of the Thames, Ted had witnessed first-hand that the government had been preparing for war for a while.

He’d seen an obvious stockpiling of munitions and other things a country going to war might need, such as medical supplies and various sorts of tinned or non-perishable foodstuffs that were now stacked waiting in warehouses. There’d also been a steady increase in new or reconditioned ships that were arriving at the docks and leaving soon afterwards with a variety of cargo.

And recently Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain had taken to the BBC radio to announce hostilities against Germany had been declared following their attack on Poland. His words had been followed within minutes by air-raid sirens sounding across London, causing an involuntary bolt of panic to shoot through ordinary Londoners. It was a false alarm but a timely suggestion of what was to come.

Understandably, the dark mood of desperation and foreboding as to what might be going to happen was hard to shake off, and during the evening of the day of Chamberlain’s broadcast Ted and Barbara had knelt on the floor and clasped hands as they prayed together.

Scandalously, in these days when most people counted themselves as Church of England believers (or, as London was increasingly cosmopolitan, possibly of Jewish or Roman Catholic faiths), neither Ted nor Barbara, despite marrying in church and having had the twins christened when they were only a few months old, were regular churchgoers, and they had never done anything like this in their lives before.

But these were desperate times, and desperate measures were called for.

As they clambered up from their knees feeling as if the sound of the air-raid siren was still ringing in their ears, they took the decision not, just yet, to be wholly honest if either Connie or Jessie asked them a direct question about why all the grown-ups around them were looking so worried. They wouldn’t yet disturb the children with talk of war and what that might mean.

The next day, when Connie mentioned the air-raid siren, Barbara explained away the sound of it by saying she wasn’t absolutely certain but she thought it was almost definitely a dummy run for practising how to warn other boats to be careful if a large cargo ship ran aground on the tidal banks of the Thames, to which Connie nodded as if that was indeed very likely the case. Jessie didn’t look so easily convinced but Barbara distracted him quickly by saying she wanted his help with a difficult crossword clue she’d not been able to fathom.

Читать дальше