Praise for

Diane Chamberlain

“So full of unexpected twists you’ll find yourself wanting to

finish it in one sitting. Fans of Jodi Picoult’s style

will love how Diane Chamberlain writes.”

—Candis

“This complex tale will stick with you forever.”

—Now magazine

“Emotional, complex and laced with suspense, this

fascinating story is a brilliant read.”

—Closer

“A moving story.”

—Bella

“A bittersweet story about regret and hope.”

—Publishers Weekly

“A fabulous thriller with plenty of surprises.”

—Star

“A brilliantly told thriller”

—Woman

“An engaging and absorbing story that’ll have

you racing through pages to finish.”

—People’s Friend

“This compelling mystery will have you

on the edge of your seat.”

—Inside Soap

“Chamberlain skilfully … plumbs the nature

of crimes of the heart.”

—Publishers Weekly

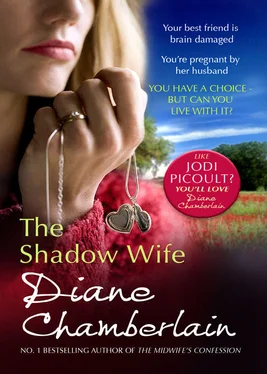

The Shadow

Wife

Diane Chamberlain

GETS TO THE HEARTOF THE STORY

www.dianechamberlain.co.uk

www.dianechamberlain.co.uk

To my extraordinary sibs,

Tom, Joann and Rob.

What a year, eh?

What fun it’s been to research a book filled with the natural beauty of the California coastline, the struggles and hopes of compassionate people … and a little bit of magic. Michael Rey nolds helped me understand what life is like on the Monterey Peninsula. Mike Woodbury and Karen (KK) Sears gave me virtual sailing lessons. Suzanne Schmidt, one of my dearest friends and an ob/gyn nurse practitioner, guided me through the medical aspects of my story. Fellow author Emilie Richards provided feedback on my story line with talent and wisdom.

I am also indebted to Richard Bingler, Liz Gardner, Tom Jackson, Craig MacBean, Patricia McLinn and Katherine Rutkowski for their various contributions to the story.

I’m grateful to my former agent, Ginger Barber, for her confidence in me, and to the editor who worked with me on this book, Amy Moore-Benson.

Big Sur, California, 1967

THE FOG WAS AS THICK AND WHITE AS COTTON BATTING, AND it hugged the coastline and moved slowly, lazily, in the breeze. Anyone unfamiliar with the Cabrial Commune in Big Sur would never know there were twelve small cabins dotting the cliffs above the ocean. Fog was nothing unusual here, but for the past seven days, it had not cleared once. Like living inside a cloud, the children said. The twenty adults and twelve children of the commune had to feel their way from cabin to cabin, and they could never be sure they’d found their own home until they were inside. Parents warned their children not to play too close to the edge of the cliff, and the more nervous mothers kept their little ones inside in the morning, when the fog was thickest. Those who worked in the garden had to bend low to be sure they were pulling weeds and not the young shoots of brussels sprouts or lettuce, and more than one man used the dense fog as an excuse for finding his way into the wrong bed at night—not that an excuse was ever needed on the commune, where love was free and jealousy was denied. Yes, this third week of summer, everyone in the commune had a little taste of what it was like to be blind.

The fog muffled sound, too. The residents of the commune could still hear the foghorns, but the sound was little more than a low moan, wrapping around them so that they had no idea from which direction it came. No idea whether the sea was in front of them or behind.

But one sound managed to pierce the fog. The cries came intermittently from one of the cabins, and the children, many of them naked, would stop their game of hide-and-seek to stare through the fog in the direction of the sound. A couple of them, who were by nature either more sensitive or more anxious than the others, shuddered. They knew what was happening. No secrets were ever kept from children here. They knew that inside cabin number four, Rainbow Cabin, Ellen Liszt was having a baby.

In the small clearing at one side of the cabin, nineteen-year-old Johnny Angel split firewood. The day was warm despite the fog, and he’d taken off his Big Brother and the Holding Company sweatshirt and hung it over the railing of the cabin’s rickety porch. Felicia, the midwife, was inside with Ellen, boiling string and scissors on the small woodstove, and he told himself they needed more firewood, even though he’d already chopped enough to last a week. Still, he lifted the ax and let it fall, over and over again, mesmerized by the thwack as it hit the logs. Every minute or so, he stopped chopping to take a drag from his cigarette, which rested on the cabin railing, and he could feel his heart beating in his bare chest. The hand holding the cigarette trembled—from the strain of chopping wood, he told himself, but he knew that was not the complete truth. He winced every time a fresh shriek of pain came from the cabin’s rear bedroom, and he was quick to pick up the ax again, hoping that the chopping would mask the sound.

When would it be over? The labor pains had started in earnest in the middle of the night, and as he and Ellen had planned, he’d run—stumbling in the darkness and the fog—to the Moonglow Cabin to awaken Felicia. Felicia had grabbed her bag of birthing paraphernalia and returned with him to Rainbow, and she’d held Ellen’s hand, speaking to her in a calming voice. It had shocked him to see Ellen in the glow of the lantern. She looked terribly young, younger than eighteen. She looked like a frightened little girl, and he felt unable to go near her, unsure of what to say or how to touch her. How to help. Her face was sweaty and she was gulping air. Johnny was afraid she might throw up. He hated seeing anyone throw up. It always made him feel sick himself.

He’d left the two women together and walked outside to the woodpile. But he hadn’t known it would take so long. How many hours had passed? All he knew was that he was on his second pack of Kools, and the menthol was beginning to make his throat ache.

Felicia had asked him if he wanted to be in the room with Ellen, and he’d stared at her, wild-eyed with surprise at the question. Hell, no, he didn’t want to be in that room. So he’d left. Now he felt like a coward for declining the offer. He knew that some men were fighting for the right to be in the delivery room these days, and that two of the men here at Cabrial had stayed with their women while they delivered. But he was not like those men. He couldn’t imagine being any closer to Ellen’s pain and fear than he was right now. Besides, that was no delivery room Ellen was in. She was lying on the old double mattress on the bare floor in the tiny bedroom they had shared for the past six months, her butt resting on newspapers, which Felicia claimed were made sterile by the printing process. Felicia was no obstetrician. She was not even a real midwife, merely the mother of four kids who were, right now, playing hide-and-seek in the fog.

When he and Ellen had first talked about it, the idea of Felicia delivering their baby had sounded fine, even appealing; after all, women used to help other women deliver babies all the time. But now that it was happening, now that Ellen’s screams made the hair on the back of his neck stand up, many things about the commune that had previously sounded appealing seemed ludicrous. His parents had rolled their eyes in disgusted resignation when he told them that he and Ellen were moving into a Big Sur commune. He told them about the large stone cabin that housed a common kitchen and huge dining room, where the commune residents took turns cooking and cleaning up and doing all the other tasks that were part of living together in a group, and his mother had asked him why he never bothered to help her cook and clean up. His parents scoffed at the names of the cabins—Rainbow, Sunshine, Stardust—and they showed real alarm when he told them there was no phone on the commune. Then they threatened him: If he dropped out of Berkeley and moved into the commune, he could expect no more money from them for school or for anything else, ever. That was fine, he said. There was little need for money in the commune. They would live off the land. They would take care of each other.

Читать дальше

www.dianechamberlain.co.uk

www.dianechamberlain.co.uk