“Oh,” said Jess. “I do hope they do. And give Buster face-ache for weeks.”

“Months,” said Frank, who had suffered a great deal more from Buster than Jess had. He was thinking of saying that Own Back could offer to do the magicking, and get the teeth mixed on purpose, when Jess noticed that someone was tapping on the window.

She jumped up to open it. Frank followed her, and found two pale little girls outside, hand in hand, their hair flapping in the wind, looking up anxiously at the window. He knew them a little by sight. They were the funny, old-fashioned girls who lived at the one house you could see from the potting shed – the cheese-coloured one. He knew the elder one was called Frances Adams, because people shouted “Sweet Fanny Adams!” after them sometimes, because they were so odd and because the younger one walked with a limp.

“Do you mean this notice?” asked the elder one.

“Yes,” said Jess. “Of course. You don’t think we put it up for fun, do you?” She was being rather haughty with them, partly because they were so peculiar, and partly because she was afraid they were going to make fun of Own Back like everyone else.

But the two little girls were in deadly earnest. The elder said: “And when you say difficult tasks, you mean that too?”

“Yes,” said Frank. “But the price goes up if it’s really difficult.”

They nodded. “This is,” said the elder, and Frank felt rather mean. They did not look as if they had much money. They wore funny patched aprons, like Victorian children, and their faces were thin and hungry. Their two pairs of big eyes stared at Frank and Jess like a picture of famine.

“What do you want us to do?” said Frank.

“Get us our Own Back,” said the elder.

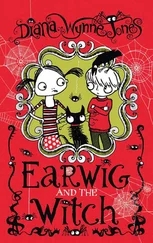

“On Biddy Iremonger. She’s a witch,” said the younger.

“I don’t think she is ,” said Jess. “Mummy says she’s just a poor old creature, and a bit wrong in the head.”

“Yes she is ,” said the elder. “She put the Evil Eye on Jenny last summer, and Jenny’s foot’s been all wrong ever since.”

“The doctor says it’s nothing,” said Jenny, “but I can’t walk and she did it.”

“And,” said Frances, “if you can do her down, we’ve got a gold sovereign that belongs to us and we’ll give it you. Promise.”

Frank and Jess were both dismayed. The little girls stared so intensely – and the idea of a whole gold sovereign was overpowering. The worst part was how much they seemed to mean what they said.

Frank asked feebly, “What do you want done to her?”

“Anything,” said Frances.

“Everything,” said Jenny.

“Suppose,” said Jess, trying to be businesslike, “we get her and make her take it off Jenny. Would that do?”

They nodded fervently. “But if she won’t,” said Frances, “do something nasty to her instead. Very nasty.”

“All right,” said Frank. “If you want.”

“Thank you,” they both said and, before Jess could think to make further arrangements, they hurried away down the path. Frances pulled Jenny, and Jenny did indeed limp badly.

“Oh, dear!” said Jess, and then, after a moment, “It’s probably only rheumatism. Mummy always says how damp that house looks.”

“Jess,” said Frank, “we can’t go and – and do things to Biddy Iremonger, can we? Even if she is a witch.”

“But she’s not,” said Jess. “It’s just them. Biddy’s only funny in the head. And I don’t think we can take their sovereign anyway. It’s not money any longer, is it?”

“So what had we better do?” Frank said helplessly. “Go and talk to Biddy? It worked with Vernon.”

“I don’t know,” said Jess. “Maybe if Jenny thinks it’s Biddy, then if we can get Biddy to say she’s taken it off somehow, Jenny might feel better. Would that work?”

Someone else was reading their notice while Jess talked. Frank happened to look sideways, and saw a horse – or perhaps a pony – outside, with a boy on its back who was bending down to read the notice. “Except it wouldn’t be Own Back,” Frank said, watching to see if they had another customer. But it seemed they had not. The boy’s smart boots moved against the pony, and the pony went on past the window. Jess looked up, hearing the hooves. “Who was that?” Frank asked.

“That’s the boy from the big house,” said Jess. “Where the Wilkins’ work. I wish he’d stayed. Kate Matthews thinks he’s super. She’s always on about him.”

“He thinks he’s too super to come near us, then,” said Frank. “And that’s a pity, because I bet he’s got real money. Anyway, Jess, let’s try going to see Biddy, shall we?”

“All right. I suppose we’d better.”

Jess was just about to put up her AWAY notice, when they heard hooves clumping again, and the big shape of the pony filled the window. Jess hurriedly put down her notice and backed away. Both she and Frank held their breath, while the boy sat on the pony and did nothing. Then, when Frank was beginning to whisper that they might as well go, the boy reached out his riding crop and rapped it on the window.

“Hark at Lord Muck!” said Frank.

Jess backed right to the potting shed door, pulling Frank with her. “Oh, you go, Frank. I daren’t.”

“Then let go of me. Coming, my lord, coming!” said Frank.

“Frank! Don’t be silly!”

“Who’s silly?” said Frank, and tore himself free. He went to the window and opened it. “Yes?” he said, looking up at the boy and wondering what was so super about him. Nothing, Frank thought, but the boy’s own idea of himself. He was just a freckled boy with red hair and a haughty look.

“Are you Own Back?” asked the boy.

“Half of it,” said Frank. “The Limited half’s by the door.”

That, of course, made the boy bend down and peer into the shed, and brought Jess up beside Frank, very pink and swinging her hair angrily. “He means me,” she said, and gave Frank a sharp kick on the ankle to teach him a lesson.

“Then I’d like you two to do a job for me,” said the boy.

“What? Revenge-Difficult-Feat-or-Treasure-anything-to-oblige,” Frank gabbled in a way that was meant to be rude. Jess kicked him again.

The boy shifted about, as if he could see Frank did not like him. “Vernon told me about you,” he said. “If you must know.”

Jess glared at Frank, and Frank realised he had better be polite if they were ever to earn that five pence. “What was it?” he asked. “Some kind of Own Back?”

“Yes,” said the boy. “Actually.” His freckly face screwed into stormy lumps. “I want you to do something about those beastly Adams kids. I can’t stand them. And I don’t know what to do about them.”

“What?” said Jess. “You mean those two funny girls who live over there?” She pointed to the cheese-coloured house.

The boy looked. “I don’t know where they live,” he said. “If you’ve got them on your doorstep, I pity you. Frankie and Jenny Adams, they’re called, and one limps. And they drive me mad. They’re always round our house, calling names and saying it’s really their house. As if I could help living there! No matter what I’m doing, one of them bobs up and says it should be hers. And I’m not supposed to hit girls, for some reason, so I can’t stop them.”

“You want us to try to stop them?” asked Jess.

“At least go and call them names,” said the boy. “Show them what it feels like.”

Both Frank and Jess rather thought the Adams girls knew what it felt like, but they did not like to say so. Frank said, “Or something to teach them a lesson?” and the boy nodded. “And I think we’d charge ten pence,” said Frank, because that seemed reasonable.

Читать дальше