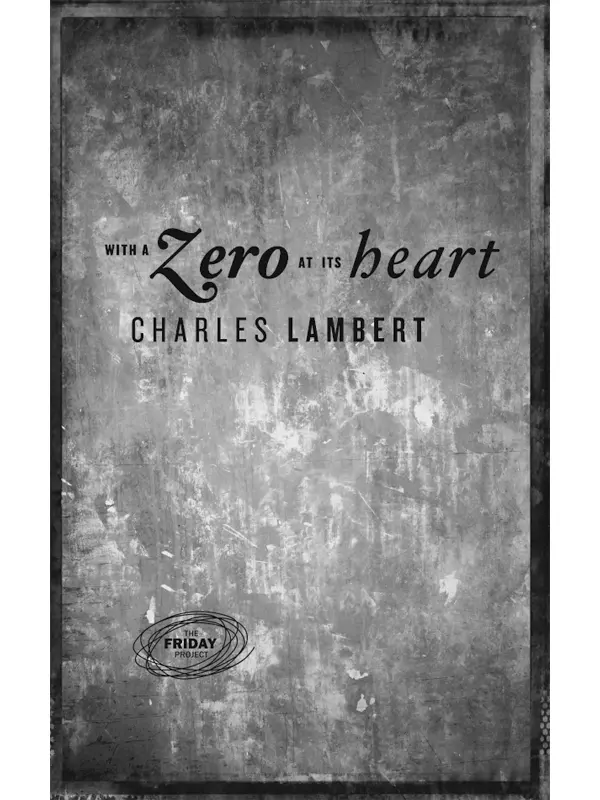

For my mother, Olive Kate Florrie Lambert (née Preece)

1916–2011

and my father, Vincent Lambert

1905–2006

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Objects or ghost balloons

Clothes or unripe strawberries

Sex or honey and wood

Travel or a harp embedded

The Body or this alien being

Danger or all that sweetness

Animals or the whelp of an alien god

Language or death and cucumbers

Money or brown sauce sandwiches

Theft or uniformly golden

Art or human-sized quilts

Work or but in the doing

Music or the global studio

Fear or the famished wall

Colours or cradling fire

Death or a sprig of leaves

Home or some other healing agent

Waiting or from star to star

Hunger or heavy bones

Nature or the purposes of love

Correspondence or coterminous with the cat

Cinema or what the centaur meant

Celebration or marking time

Books or utterly pliant and clinging

Coda or one bright brief beat

Also by Charles Lambert

Copyright

About the Publisher

He has never seen a ship inside a bottle but the day he discovers their existence he knows that he wants one more than anything in the world. He is seven years old. He imagines men no bigger than his fingertip working at the building of the ship, singing as they nail long boards to the hull and sew the rigid sailcloth panels for the mast, tall and straight as a tree, and coat the ship with burning tar to make sure it never sinks. He watches them gather on the deck. There is a bird above their heads. He imagines he is on a ship and there is glass all around him, as far as the eye can see.

He comes across the pendant in his great-aunt’s drawer. It is heavy, warm in his hand, the size of a just-fledged bird. At the heart of the pendant is the skeletal form of some insect, some winged insect, more than an inch long, longer than any insect he has ever seen, its flesh eaten out and engulfed by the same warm yellow that surrounds it. It is hollowed and sustained, its wings barely furled, it floats in this substance for which he has no name, which could be plastic but isn’t. There is a loop for a chain at the top, but he will never wear it. It is amber. The insect has been trapped inside for a million years.

His father buys him a bicycle, but it is the wrong sort. The bicycle he wants has swept-down racing handlebars and no mudguards and is green and white. This one has small wheels and can fold into two. It is the colour of bottled damsons. He pushes his new bicycle into the road and rides away as hard and fast as he can, but it is not fast enough; it will never be fast enough to escape the shame of the thing that bears him. His eyes are blinded by tears. When he skids and scrapes the skin from his arms he is glad. He shows his father the blood. This is your blood, he thinks but dare not say.

He finds an owl pellet in the barn beside his house. It is round, the weight of a dove’s egg, and roughly made, as though pressed from earth or some other substance he can’t identify. He does what he’s read in his book, soaking and prising it apart. Some of it crumbles and is thrown away, but he’s left in the end with a tangle of tiny bones, as fine as rain and puzzling, like a jigsaw without its box. One by one, he lays the bones out on his table until he finds at their heart a hollow skull, a jewel. That night he sees an owl swoop from the bare eye of the barn towards his bedroom window.

His favourite aunt gives him a typewriter. The first thing he writes is a story about people who gather in a room above a shop to invoke the devil. When they hear the clatter of cloven hooves on the stairs the story ends, but the typewriter continues to tap out words, and then paragraphs, and then pages until the floor is covered. He picks them up and places them in a box as fast as they come, and then a second box, and then a third. There is no end to it. I am nothing more than a channel, he whispers to himself, and the typewriter pauses for a moment and then, on a new sheet, types the word Possession.

He’s looking for Christmas presents in an antique shop behind the station when he sees a small, black lacquered box with a hinged lid. On the lid is a row of Chinamen. Their robes are exquisitely traced in gold, their wise heads tiny ovals of ivory, inset, like split peas bleached to bone. They seem to be waiting to be received like supplicants before an invisible benefactor, some mandarin perhaps. Many years later, the box survives a fire, but the shine of its lacquer is destroyed and the fine gold lines that delineate the robes of the men are seared away. What’s left is the row of heads, like ghost balloons, tethered down by invisible cords to the general darkness.

He reads his work at an international poetry festival. The local paper calls him a small, bearded man with one earring, which is two parts false and two parts true. At the party that evening, horribly drunk, coked-up, he pretends to adore the work of a Scottish poet, whose shallow musings he despises, and ignores the two poets he most admires out of shyness and misplaced pride. These poets both die soon after, the first beneath a passing car, the second alone, choked by her own vomit. He feels accountable for their deaths. He takes the reading fee he has been given and uses it to buy a Bullworker – a contraption of wires and steel that will make him invincible.

Before leaving the country he buys himself a single-lens reflex camera. It is more than he can afford, but how else will they believe him? Without the lens his eye is drawn by what moves, by skin and sinew and eyes and mouths, by the shifting of an arm against a table or the way one shoulder lifts without the other, but he’s too inhibited to photograph what he sees. He’s scared it might answer him back. Through his lens, what he sees is the perfect empty symmetry of doors and windows, and the way light catches the concrete of a bollard a boy has been sitting on moments before, the light still there, the warmth refusing to be held.

They live in a rented house with a billiards room, a spiral staircase and a ghost. The local laundrette is filled with drunken Irish poets. It is cold, and getting colder daily. When they’re forced to move, traipsing knee-deep in snow through the back streets of London, they take a single trophy with them, a Chinese duck with a pewter body, and brass wings and beak. The duck splits into two across the middle; they use it to keep dope, papers, all they need to hold the misery of their failure at bay. It is their stash duck and they love it. Everything else from that time has gone, everything except the ghost. The ghost is alive inside the duck.

His father keeps his ties in a flat wooden box. Each tie is tightly rolled, with the wide end at its heart. There are ties of all widths, all styles. His father throws nothing away and will never leave the house without a tie. The ties are held in place by a wooden grille, placed over them before the lid is closed. His father dies and he finds himself with the box of ties, many of them gifts he has bought at airports or hurriedly in shops he would normally avoid. He opens the box and rolls the ties open across his bed, their silk and wool a reproach to him as they wait to be taken up and worn.

Читать дальше