In the late seventeenth century, an Irish philosopher, William Molyneux, suggested the following mental experiment to his friend John Locke:

Suppose a man born blind, and now adult, and taught by his touch to distinguish between a cube and a sphere [ … ] Suppose then the cube and the sphere placed on a table, and the blind man made to see: query, Whether by his sight, before he touched them, he could now distinguish and tell which is the globe, which the cube?

Could he? In the years that I have been asking this question I’ve found that the vast majority of people believe that the answer is no. That the virgin visual experience needs to be linked to what is already known through touch. Which is to say, that a person would need to feel and see a sphere at the same time in order to discover that the gentle, smooth curve perceived by the fingertips corresponds to the image of the sphere.

Others, the minority, believe that the previous tactile experience creates a visual mould. And that, as a result, the blind man would be able to distinguish the sphere from the cube as soon as he could see.

John Locke, like most people, thought that a blind man would have to learn how to see. Only by seeing and touching an object at the same time would he discover that those sensations are related, requiring a translation exercise in which each sensory mode is a different language, and abstract thought is some sort of dictionary that links the tactile words with the visualized words .

For Locke and his empiricist followers, the brain of a newborn is a blank page, a tabula rasa ready to be written on. As such, experience goes about sculpting and transforming it, and concepts are born only when they acquire a name. Cognitive development begins on the surface with sensory experience, and, then, with the development of language, it acquires the nuances that explain the deeper and more sophisticated aspects of human thought: love, religion, morality, friendship and democracy.

Empiricism is based on a natural intuition. It is not surprising, then, that it has been so successful and that it dominated the philosophy of the mind from the seventeenth century to the time of the great Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget. However, reality is not always intuitive: the brain of a newborn is not a tabula rasa . Quite the contrary. We already come into the world as conceptualizing machines.

The typical café discussion reasoning comes up hard against reality in a simple experiment carried out by a psychologist, Andrew Meltzoff, in which he tested a version of Molyneux’s question in order to refute empirical intuition. Instead of using a sphere and a cube, he used two dummies: one smooth and rounded and the other more bumpy, with nubs. The method is simple. In complete darkness, babies had one of the two pacifiers in their mouths. Later, the pacifiers are placed on a table and the light is turned on. And the babies looked more at the pacifier they’d had in their mouths, showing that they recognize it.

The experiment is very simple and destroys a myth that had persisted over more than three hundred years. It shows that a newborn with only tactile experience – contact with the mouth, since at that age tactile exploration is primarily oral as opposed to manual – of an object has already conceived a representation of how it looks. This contrasts with what parents typically perceive: that newborn babies’ gazes often seem to be lost in the distance and disconnected from reality. As we will see later, the mental life of children is actually much richer and more sophisticated than we can intuit based on their inability to communicate it.

Atrophied and persistent synaesthesias

Meltzoff’s experiment gives – against all intuition – an affirmative response to Molyneux’s question: newborn babies can recognize by sight two objects that they have only touched. Does the same thing happen with a blind adult who begins to see? The answer to this question only recently became possible once surgeries were able to reverse the thick cataracts that cause congenital blindness.

The first actual materialization of Molyneux’s mental experiment was done by the Italian ophthalmologist Alberto Valvo. John Locke’s prophecy was correct; for a congenitally blind person, gaining sight was nothing like the dream they had longed for. This was what one of the patients said after the surgery that allowed him to see:

I had the feeling that I had started a new life, but there were moments when I felt depressed and disheartened, when I realized how difficult it was to understand the visual world. [ … ] In fact, I see groups of lights and shadows around me [ … ] like a mosaic of shifting sensations whose meaning I don’t understand. [ … ] At night, I like the darkness. I had to die as a blind person in order to be reborn as a seeing person.

This patient felt so challenged by suddenly gaining sight because while his eyes had been ‘opened’ by the surgery, he still had to learn to see. It was a big and tiresome effort to put together the new visual experience with the conceptual world he had built through his senses of hearing and touch. Meltzoff proved that the human brain has the ability to establish spontaneous correspondences between sensory modalities. And Valvo showed that this ability atrophies when in disuse over the course of a blind life.

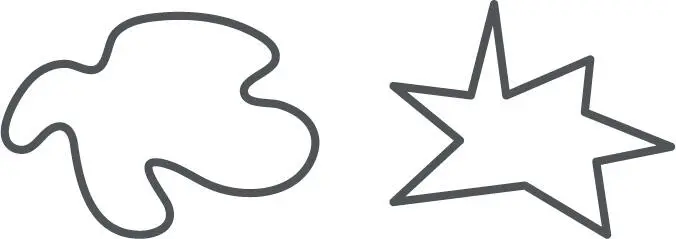

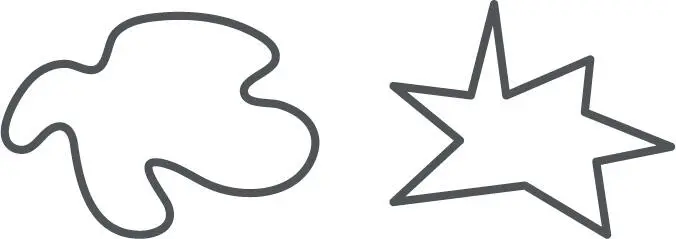

On the contrary, when we experience different sensory modalities, some correspondences between them consolidate spontaneously over time. To prove this, my friend and colleague Edward Hubbard, along with Vaidyanathan Ramachandran, created the two shapes that we see here. One is Kiki and the other is Bouba. The question is: which is which?

Almost everyone answers that the one on the left is Bouba and the one on the right is Kiki. It seems obvious, as if it couldn’t be any other way. Yet there is something strange in that correspondence; it’s like saying someone looks like a Carlos . The explanation for this is that when we pronounce the vowels /o/y/u/, our lips form a wide circle, which corresponds to the roundness of Bouba. And when saying the /k/, or /i/, the back part of the tongue rises and touches the palate in a very angular configuration. So the pointy shape naturally corresponds with the name Kiki.

These bridges often have a cultural basis, forged by language. For example, most of the world thinks that the past is behind us and the future is forward. But that is arbitrary. For example, the Aymara, a people from the Andean region of South America, conceive of the association between time and space differently. In Aymara, the word ‘nayra’ means past but also means in front, in view. And the word ‘quipa’, which means future, also indicates behind. Which is to say that in the Aymaran language the past is ahead and the future behind. We know that this reflects their way of thinking, because they also express that relationship with their bodies. The Aymara extend their arms backwards to refer to the future and forwards to allude to the past. While on the face of it this may seem strange, when they explain it, it seems so reasonable that we feel tempted to change our own way of envisioning it; they say that the past is the only thing we know – what our eyes see – and therefore it is in front of us. The future is the unknown – what our eyes do not know – and thus it is at our backs. The Aymara walk backwards through their timeline. Thus, the uncertain, unknown future is behind and gradually comes into view as it becomes the past.

Читать дальше