This wasn’t evolutionary thinking; it was just data management. The knowledge would fill volumes (one man alone, the German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, published a thirty-volume account of his travels in South America), making all the more necessary an overview, an organizing principle, that could be apprehended at a glance: an illustration. But the illustrators now needed two dimensions, not one, and so the ladder turned into a trunk, and the trunk sprouted limbs, and the limbs diverged into branches. This offered more scope, sideways as well as up and down, for arranging the varied abundance of known creatures.

The tree of life was an old symbol by then, an old phrase, dating back at least to those mentions in Genesis and Revelation. The tree had also served as a model for family histories—the genealogical tree or pedigree of a German duke, for instance. Now the secularized tree became useful for organizing biology. Among the first to embrace this convention was another Frenchman, Augustin Augier, who wrote in 1801 that “ a figure like a genealogical treeappears to be the most proper to grasp the order and gradation” of what concerned Augier: the diversity of plants.

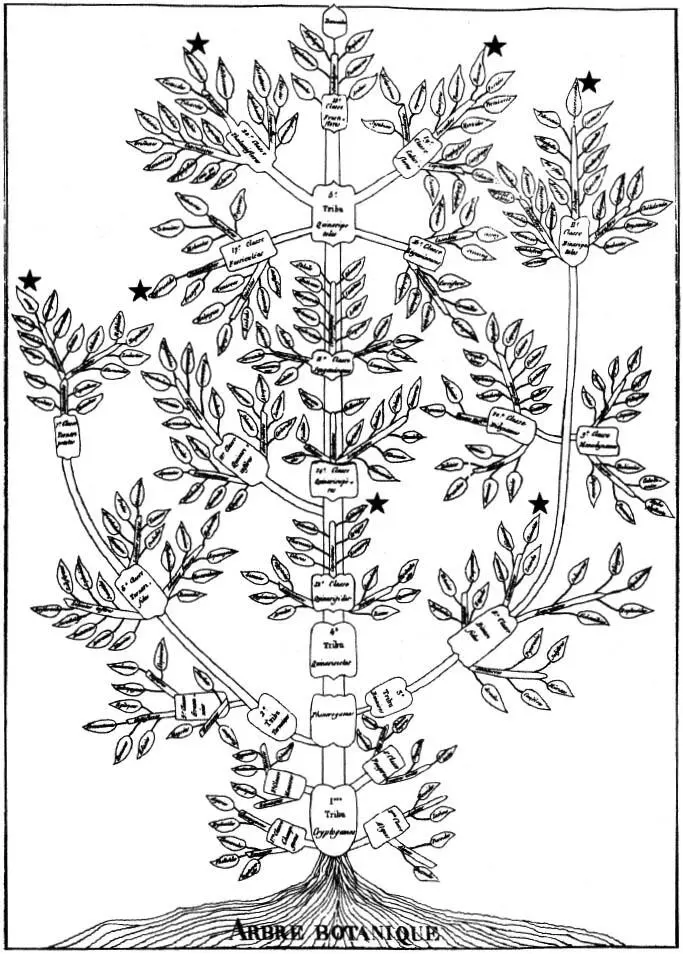

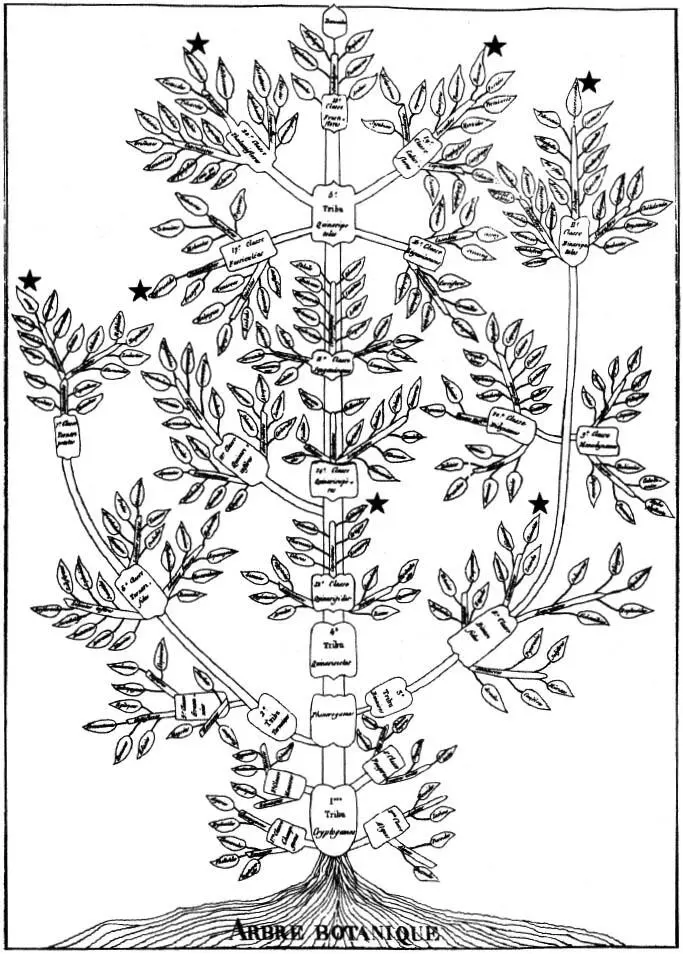

Augier was an obscure citizen of the French Republic, living in Lyon, working on botany part-time; his real profession was unknown, his biographical details lost, even to a historian of Lyonnais botanists writing a hundred years later. Augier disappeared. But he left behind a book, a little octavo volume, in which he proposed a new classification of plants, “ according to the order that Nature appearsto have followed.” That is, a “natural order,” as opposed to an artificial classification system based merely on human whim or convenience. And in the book was a figure representing that system: his arbre botanique (botanical tree). Its trunk and limbs look almost as orderly and stiff as a menorah, but its sideways branching and copious leafing suggest a rife multiplicity of plant forms.

Again, this didn’t imply any heretical ideas about origins. Augier was no evolutionist before his time. His natural order wasn’t meant to suggest that all plants had descended from common ancestors by some sort of material process of transformation. God was their maker, shaping the varied forms individually: “ It appears, and one can hardly doubt it, that the Creator, when making flowers, followed certain proportions and progressions in the number of their different parts.” Augier’s contribution, as he saw it, was discovering those proportions and progressions—design principles that had satisfied the Deity’s neat sense of pattern—and using them after the fact to organize botanical knowledge into a tidy system.

Augier wasn’t the first naturalist to hanker for a natural order of nature’s diversity. Aristotle had classified animals as “bloodless” and “blooded.” In the first century of our era a Greek physician named Dioscorides, attached to the Roman army, gathered lore on more than five hundred kinds of plants, arranging them in a compendium mainly on the basis of their medicinal, edible, and perfumatory uses. That book, in various reprints and translations, served as a trusted botany text for the next fifteen hundred years. Toward the end of its run, around the time of the Renaissance, as people traveled more widely and paid closer attention to the empirical details of nature, old Dioscorides gave way to newer illustrated herbals. These were essentially field guides to botany, graced with better illustrations based on improvements in drawing and woodcut techniques, but still organized for convenience of use, not natural order. In the sixteenth century, Leonhart Fuchs produced one of those books, an herbal cataloging hundreds of plants, beautifully illustrated and arranged in alphabetical order. Two centuries later, the great systematizer Carl Linnaeus described a genus of plants with purplish red flowers, naming it Fuchsia in honor of Leonhart Fuchs (and hence we got also the color, fuchsia). Linnaeus himself, a Swede who traveled widely as a young man and then took up a professorial life in Uppsala, emerged from this herbalist tradition but went beyond it.

Augier’s Arbre Botanique , 1801.

Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae , as first published in 1735, was a unique and peculiar thing: a big folio volume of barely more than a dozen pages, like a coffee-table atlas, in which he outlined a classification system for all the members of what he considered the three kingdoms of nature: plants, animals, and minerals. Notwithstanding the inclusion of minerals, what matters to us is how Linnaeus viewed the kingdoms of life.

His treatment of animals, presented on one double-page spread, was organized into six columns, each topped with a name for one of his classes: Quadrupedia, Aves, Amphibia, Pisces, Insecta, Vermes. Quadrupedia was divided into several four-limbed orders, including Anthropomorpha (mainly primates), Ferae (doggish forms such as wolves and foxes, plus cat forms such as lions and leopards, in addition to bears), and others. His Amphibia encompassed reptiles as well as amphibians, and his Vermes was a catchall group containing not just worms, leeches, and flukes but also slugs, sea cucumbers, starfish, barnacles, and other sea animals. He divided each order further into genera (with some recognizable names such as Leo, Ursus, Hippopotamus, and Homo), and each genus into species. Apart from the six classes, Linnaeus also gave a half column to what he called Paradoxa: a wild-card assemblage of mythic chimeras and befuddling but real creatures, including the unicorn, the satyr, the phoenix, the dragon, and a certain giant tadpole ( Pseudis paradoxa , under its modern label) that, strangely, paradoxically, shrinks during metamorphosis into a much smaller frog. Across the top of the chart ran large letters: CAROLI LINNAEI REGNUM ANIMALE. His animal kingdom. It was a provisional effort, grand in scope, integrated, but not especially original, to make sense of faunal diversity based on what was known and believed at the time. Then again, animals weren’t Linnaeus’s specialty.

Plants were. His classification of the vegetable kingdom was more innovative, more comprehensive, and more orderly. It became known as the “sexual system” because he recognized that flowers are sexual structures, and he used their male and female organs—their stamens and pistils, those delicate little stems sticking up to present and receive pollen—for characterizing his groups. Linnaeus defined twenty-three classes, into which he placed all the flowering plants, based on the number, size, and arrangement of their stamens. Then he broke each class into orders, based on their pistils. To the classes, he gave names such as Monandria, Diandria, and Triandria (one husband, two husbands, three husbands), and, within each class, ordinal names such as Monogynia, Digynia, and Tryginia (numbers of wives, yes, you get the idea), thereby evoking all sorts of polygamous and polyandrous ménages that must have caused lewd smirks and disapproving scowls among his contemporaries. A plant of the Monogynia order within the Tetrandria class, for instance: one wife with four husbands. Linnaeus himself seems to have enjoyed the sexy subtext. And it didn’t prevent his botanical schema from becoming the accepted system of plant classification throughout Europe.

Our man Augustin Augier, coming along a half century later with his botanical tree of classification, seems to have seen himself challenging Linnaeus’s overly neat sexual system. “ Stamen number is a striking character,” Augier conceded, but “not when it comes to the examination of plants”—that is, not always unambiguous and therefore not reliable as a basis for organizing the great jumble of botanical life. He nodded respectfully to Linnaeus—also to the French botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, who had sorted plants into roughly seven hundred genera based on their flowers, their fruits, and other bits of their anatomy—and offered his own system, using multiple characters for different levels of sorting and to resolve the ambiguities and fine gradations. “ This figure, which I call a botanical tree , shows the agreements which the different series of plants maintain amongst each other, although detaching themselves from the trunk; just as a genealogical tree shows the order in which different branches of the same family came from the stem to which they owe their origin.” All discrete, yet all connected: bits of the same tree.

Читать дальше