I was too idealistic to want more money than I needed to subsist, too arrogant to envy Heisler, and so to me the rich were mainly a curiosity, interesting for the conspicuousness of both their consumption and their thrift. When V and I visited her other grandparents, at their country estate outside the city, they showed me the little paintings by Renoir and Cézanne in their living room and served us stale store-bought cookies. At Tavern on the Green, where we were taken to dinner by my brother Bob’s in-laws, a pair of psychoanalysts who had an apartment not a lot smaller than Albert’s, I was appalled to learn that if you wanted a vegetable with your steak you had to pay extra for it. The money seemed of no consequence to Bob’s father-in-law, but we noticed that one of the mother-in-law’s shoes was held together with electrical tape. Heisler, too, was given to grand gestures, like flying Tom’s soon-to-be wife out from Chicago for a weekend. But he paid Tom $12,500 for the loft conversion, approximately one-eighth of what it would have cost with a New York contractor.

It was people like Tom and me who didn’t recognize the value of what they had in hand. Tom realized too late that he could easily have charged Heisler two or three times as much, and I left Manhattan, in mid-August, owing $225 to St. Luke’s Hospital. To celebrate the end of the summer and also, I think, our engagement to be married, V and I had gone to dinner at a Cuban restaurant on Columbus Avenue, Victor’s, which her former boyfriend, a Cuban, had frequented. I started with black bean soup and was a few spoonfuls into it when the beans seemed to come alive on my tongue, churning with a kind of malevolent aggression. I reached into my mouth and pulled out a narrow shard of glass. V flagged down our server and complained to him. The server summoned the manager, who apologized, examined the piece of glass, disappeared with it, and then came back to hustle us out of the restaurant. I was pressing a napkin to my tongue to stanch the bleeding. At the front door, I asked if it was okay for me to keep the napkin. “Yes, yes,” the manager said, shutting the door behind us. V and I hailed our only cab of the summer and went directly to St. Luke’s, our neighborhood hospital. Eventually a doctor told me that my cut would heal quickly and did not require stitches, but I had to wait a couple of hours to receive this information and a tetanus shot. Directly across from me, in one of the corridors where I waited, a young African-American woman was lying on a gurney with a gunshot wound in her bared abdomen. The wound was leaking pinkish fluid but was evidently not life-threatening. I can still see it vividly, a .22-caliber-size hole, the thing I’d walked in fear of.

Fifteen years later, after being married and divorced, I built a work studio in a loft on 125th Street, following Tom’s example and hanging my own drywall, wiring my own outlets. I’d gotten smarter about money, and I was able to jump on a cheap space in Harlem because I wasn’t scared of the city anymore. I had a personal connection with the Harlemites in my building, and after work I could go downtown and safely walk with my friends on the alphabet streets, which were being colonized by young white people. In time, on the strength of the sales of the book I’d written in Harlem, I bought my own Upper East Side co-op and became a person who took younger friends and relatives to dinner at places they couldn’t have afforded.

The city’s dividing line had become more permeable, at least in one direction. White power had reasserted itself through the pressure of real-estate prices and police action. In hindsight, the era of white fear seems most remarkable for having lasted as long as it did. Of all my mistakes as a twenty-one-year-old in the city, the one I now regret the most was my failure to imagine that the black New Yorkers I was afraid of might be even more afraid than I was.

On my last full day in Manhattan that summer, I got a check from Greg Heisler for my last four weeks of work. To cash it, I had to go to the European American Bank, a strange little hexagonal building that sat on a bite of dismal parkland taken out of SoHo’s southeast flank. I don’t remember how many hundred-dollar bills I was given there—maybe it was six, maybe nine—but it seemed to me a dangerous amount of cash to carry in my wallet. Before I left the bank, I discreetly slipped the bills into one of my socks. Outside, it was one of those bright August mornings when a cold front flushes the badness from the city’s sky. I headed straight to the nearest subway, anxious about my wealth, hoping I could pass as poor to someone who wanted the money in my sock more than I did.

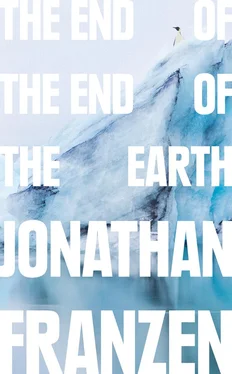

If you could see every bird in the world, you’d see the whole world. Things with feathers can be found in every corner of every ocean and in land habitats so bleak that they’re habitats for nothing else. Gray Gulls raise their chicks in Chile’s Atacama Desert, one of the driest places on Earth. Emperor Penguins incubate their eggs in Antarctica in winter. Goshawks nest in the Berlin cemetery where Marlene Dietrich is buried, sparrows in Manhattan traffic lights, swifts in sea caves, vultures on Himalayan cliffs, chaffinches in Chernobyl. The only forms of life more widely distributed than birds are microscopic.

To survive in so many different habitats, the world’s ten thousand or so bird species have evolved into a spectacular diversity of forms. They range in size from the ostrich, which can reach nine feet in height and is widespread in Africa, to the aptly named Bee Hummingbird, found only in Cuba. Their bills can be massive (pelicans, toucans), tiny (Weebills), or as long as the rest of their body (Sword-billed Hummingbirds). Some birds—the Painted Bunting in Texas, Gould’s Sunbird in South Asia, the Rainbow Lorikeet in Australia—are gaudier than any flower. Others come in one of the nearly infinite shades of brown that tax the vocabulary of avian taxonomists: rufous , fulvous , ferruginous , bran-colored , foxy .

Birds are no less diverse behaviorally. Some are highly social, others anti. African queleas and flamingos gather in flocks of millions, and parakeets build whole parakeet cities out of sticks. Dippers walk alone and underwater, on the beds of mountain streams, and a Wandering Albatross may glide on its ten-foot wingspan five hundred miles away from any other albatrosses. New Zealand Fantails are friendly and may follow you on a trail. A caracara, if you stare at it too long, will swoop down and try to knock your head off. Roadrunners kill rattlesnakes for food by teaming up on them, one bird distracting the snake while another sneaks up behind it. Bee-eaters eat bees. Leaftossers toss leaves. The Oilbird, a unique nocturnal species of the American tropics, glides over avocado trees and snatches fruit on the fly; Snail Kites do the same thing, except with snails. Thick-billed Murres can dive underwater to a depth of 700 feet, Peregrine Falcons downward through the air at 240 miles an hour. A Wren-like Rushbird will spend its entire life beside one half-acre pond, while a Cerulean Warbler may migrate to Peru and then find its way back to the tree in New Jersey where it nested the year before.

Birds aren’t furry and cuddly, but in many respects they’re more similar to us than other mammals are. They build intricate homes and raise families in them. They take long winter vacations in warm places. Cockatoos are shrewd thinkers, solving puzzles that would challenge a chimpanzee, and crows like to play. (Check out the YouTube video of a crow in Russia sledding down a snowy roof on a plastic lid, flying back up with the lid in its beak, and sledding down again.) And then there are the songs with which birds, like us, fill the world. Nightingales trill in the suburbs of Europe, thrushes in downtown Quito, hwameis in Chengdu. Chickadees have a complex language for communicating, not only to one another but to every bird in their neighborhood, how safe or unsafe they feel from predators. Some lyrebirds in eastern Australia sing a tune their ancestors may have learned from a settler’s flute nearly a century ago. If you shoot too many pictures of a lyrebird, it will add the sound of your camera to its repertoire.

Читать дальше