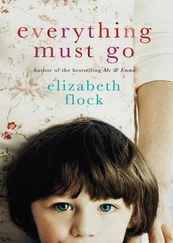

There she was. This beautiful head of wavy light brown hair on the verge of being blond.

“That’s her,” I said. I thought when the time came I’d feel a rush of … something. I don’t know. Some kind of lightning bolt. Instead, it was as natural as looking at the sky. It was as if I’d known her all my life. Like I’d willed her to us.

Bob put his hand on my shoulder and leaned in closer to see. I slid the album over so he could get a better look. I traced the line of her face and looked at him and caught a flicker of something I’d rarely seen in him. He hid it when he felt me turn to him, but there was no mistaking it. He looked defeated. Resigned. I opened my mouth to say something but closed it because I couldn’t think of what to say. He’d folded into himself like a bat. His hands tucked into his armpits. Feeling the heaviness of the silence the adoption counselor said:

“I’ll give you two some privacy.”

She closed the door quietly behind her.

“What?” I asked him.

“Nothing,” he said. He didn’t look at me. He pulled the book over and smiled at her picture and then turned his face up like he was trying to make up for the grimace.

“You made a face,” I said.

“No, I didn’t.”

“You made a face. If you’ve got something to say just say it,” I said.

“No. Yeah. I mean, she’s beautiful. Clearly. But—”

Maybe I was too quick with the defensive/offensive “but what?” but I was upset. How could he be backing off? We’d come this far. We’d talked about adopting a child with special needs. He seemed to think it was a good idea before picture day. He told me that if it would make me happy then fine. Okay, so he was doing it for me, but is there anything wrong with that?

I think it was because he saw that I wanted it. He knew I wanted to be extraordinary. Not ordinary … extraordinary. Making a difference in a child’s life is one thing … making a difference to a child with special needs—that felt right to me. Lynn kept asking me if there was any rhyme or reason to it. Had my mom worked with retarded kids? she asked. What the hell did I think was going to happen? she’d asked. Did I think I’d win some award or have a street named after me? she’d asked. I couldn’t explain it. Not to her and I suppose not to Bob. Not well enough anyway.

So there we were staring at Cammy in a three-ring binder.

“But what? Finish your sentence,” I said.

“Nothing.”

Then he cleared his throat the way he does when he has something to say.

“It’s just—” more throat clearing “—I mean, are we sure we can take on a crack baby?”

“I hate that term.”

“You know what I mean. A child born addicted. Whatever. It’s a huge thing.”

“We talked about this,” I said. “We’ve been over this. I thought you were good with it. We were on the same page. I can’t believe you’re changing your mind.”

“Sam, we only started talking about it when we heard there was a long wait.”

“Yeah, so?”

“So … it’s only been a few weeks, four, tops. It’s a big thing. Maybe we should take a little more time …”

“But here she is! She’s the one. She’s our girl. I don’t care what she’s got in her system. And up until now you didn’t care either. At least that’s what you said. Were you lying?”

“Jesus no. It’s just that it’s … real.”

“Yeah, well, having children is real, Bob. We’ve spent how many thousands of dollars trying to make one of our own. That was real, right?”

“You know what I mean. This is a child with addictions …”

“… and they said it wouldn’t be long until it’s out of her system altogether. They said the lasting effects are minimal. So she’ll have trouble concentrating in school. We’ll hire tutors.”

“You really want this,” he said. Like it was a Christmas present that cost a little too much but that he’d be willing to buy to make me happy.

“I really want this.”

He looked at her picture, smiled up at me and touched her photo like I had.

“Welcome home, Cameron Friedman,” he said.

I threw myself into hugging him. I hadn’t asked him if he really wanted this. I figured me wanting it was enough for the both of us.

My mother used to say there’s no such thing as too much love. But what happens when there’s not enough love? What if, when you look at your husband you feel blank like a piece of notebook paper?

I remember my mother leaning over the bathroom sink applying coral lipstick, checking her teased hair to make sure the bouffant was not too big because big is tacky. I would sit on the edge of the bathtub, watching her wave wet with nail polish fingertips, getting ready to go out with my dad. Even when she wasn’t in it, the bathroom smelled like nail polish, Joy perfume and White Rain hair spray. Her closet had sachets so her clothes all smelled like roses, so that’s what she was: petals and softness and color.

Mom’d say things like, “Rule Number One, never ever leave the house without lipstick.” She put it on right after brushing her teeth and as soon as I was allowed to wear it, I did the same thing. She told me Dad never ever saw her without it. She said in a fire there are two things you need to do before you run out, lipstick and mascara. I started having all kinds of nightmares involving fire and she told me that Dad always kept fresh batteries in the smoke detectors, he’s that kind of father, she said. For a long time if someone mentioned their father I’d ask if he changed the batteries in the smoke detectors.

I remember she’d tell me I was meant for greatness and boy oh boy just wait something special was surely in store and boy oh boy would I look back and laugh at how I never believed her. I didn’t believe her when she said I would meet someone who I would love more than chocolate. I didn’t believe her when she said I would love being married just like she did or when she said just you wait, Samantha. You’ll see. The love you’ll have for your children will be beyond your imagination.

It was definitely beyond my imagination the work it took to live day to day with Cammy. Lynn’s son, Tommy, was only a few months old at the time, so we hadn’t been able to spend time together, with or without the kids. Forget babysitters. No one had the patience for Cammy. Our social worker said the more exposure Cammy had to other kids her age, the better off she’d be. I thought I’d try the Mommy & Me class at our health club.

When you have a child born addicted to drugs you notice things you never before gave a second thought to, like taking Cam to the club. I’d never heard the loud music pumping bass like a punch, coming in through the revolving doors, which alone were confusing to her, I could see. I hadn’t thought of lights being particularly bright, but they were suddenly blinding. The line of people checking in felt interminable—had it always taken so long?

All this made Cammy hysterical. Hysterical. People turned around. They stared. Some shook their heads like I was a criminal for bringing her here. I found myself embarrassed. Looking back, I wish I’d said, “Really? Really. You’re upset about the noise my daughter’s making and you don’t mind Wang Chung blaring overhead?” Deep down, though, I couldn’t blame them. I was one of them not so long ago.

By the time I signed us in, my arm was breaking under the constant squirm of frantic Cammy. My other shoulder was pinched in the straps of the baby bag I hadn’t been able to readjust. I was sweating, passing the spin studio. The pilates room. The office for personal trainers. I was walking past my former life. By the time we made it to class I was exhausted. I looked in through the window in the door and all the moms were talking with each other. So pleasant. Then I looked at their kids. The class was for mothers and their two-year-olds. They were strict about the age apparently. So when I looked in at them I was shocked to see they were nearly twice Cammy’s size. I looked from her to them and back at her. They were healthy of course. They’d been breast-fed healthy milk. They’d had carefully scrutinized pregnancies. The babies were all bobbing up and down happily on their mothers’ laps, waiting for class to start. I turned and whisked us both out of there and never again went to the health club.

Читать дальше