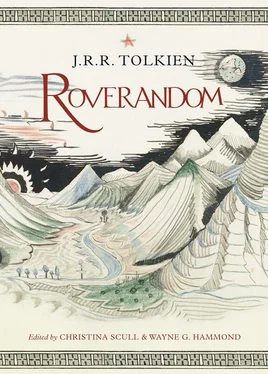

Roverandom

By

J.R.R. Tolkien

Edited by

CHRISTINA SCULL &

WAYNE G. HAMMOND

This book is dedicated to the memory of

Michael Hilary Reuel Tolkien

1920–1984

Contents

Title Page

Dedication This book is dedicated to the memory of Michael Hilary Reuel Tolkien 1920–1984

Introduction

Roverandom

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Notes

Works by J.R.R. Tolkien

Copyright

About the Publisher

IN THE SUMMER of 1925 J.R.R. Tolkien, his wife Edith, and their sons John (nearly eight), Michael (nearly five), and Christopher (not yet one year old) went on holiday to Filey, a town on the Yorkshire coast which is still popular with tourists. It was an unexpected holiday, in celebration of Tolkien’s appointment as Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford, which he was to take up on 1 October that year; and it was perhaps intended as a period of rest for him before he not only assumed that post, but for two terms would continue to teach at the University of Leeds, as his old and new appointments overlapped. For three or four weeks at Filey – as explained below, the dates are uncertain – the Tolkiens rented an Edwardian cottage which may have belonged to the local postmaster, built high on a cliff overlooking the beach and the sea. From this vantagepoint the view to the east was unobstructed, and young John Tolkien was thrilled when for two or three beautiful evenings the full moon rose out of the sea and shone a silver ‘path’ across the water.

At this time Michael Tolkien was extremely fond of a miniature toy dog, made of lead and painted black and white. He ate with it and slept with it, and carried it around with him; he was reluctant to let it go even to have his hand washed. But during the holiday at Filey he went for a walk with his father and elder brother, and in the excitement of skimming stones into the sea put his toy down, onto the beach of white shingle. Against this background the tiny black and white dog became virtually invisible, and was lost. Michael was heartbroken when his toy could not be found, although the two older boys and their father searched for it that day and the next.

The loss of a favourite toy is of great moment to a child, and no doubt it was with this in mind that Tolkien was inspired to invent an ‘explanation’ for the occurrence: a story in which a real dog, named Rover, is turned into a toy by a wizard, is lost on a beach by a boy very much like Michael, meets a comical ‘sand-sorcerer’, and has adventures on the moon and under the sea. At least, that is the full story of Roverandom , as it was finally set down on paper. That it did not emerge fully formed, but was devised and told in several parts, might be deduced from its episodic nature, and from its length; and in fact this is verified by a tantalizingly brief entry in Tolkien’s diary (written almost certainly in 1926 as part of a résumé of events of 1925) about the composition of Roverandom at Filey: ‘The tale of “Roverandom” written to amuse John (and myself as it grew) got done.’ Unhappily it is not possible to know exactly what Tolkien meant by ‘got done’ – no more, perhaps, than that the complete story (as it then stood) was told during the holiday. The parenthetical note, however, confirms that the tale did indeed grow in the telling.

It is curious that only John is mentioned in this diary statement, when it was Michael’s misfortune which lay behind the story of Rover. It may be that Michael was satisfied with its earliest episode, which explained the disappearance of his toy, and was less interested than John in its continuation. Tolkien himself clearly warmed to the tale, which becomes more sophisticated as it proceeds. But it is nowhere recorded, and no one can now say, exactly in what form Roverandom was originally conceived – whether all of its clever twists of language and its allusions to myths and legends, for example, were part of the story from the beginning, or were added when Roverandom was at last written down.

Tolkien also wrote in his diary, after the same interval of a few months, that the family went to Filey (from Leeds) on 6 September 1925 and remained there until 27 September. But at least the first of these dates cannot be correct (and indeed is mistakenly recorded in the diary as a Saturday rather than a Sunday). Given that John Tolkien’s memory of the full moon shining upon the sea is still vivid, and that the sight was surely the inspiration for Rover’s journey along a ‘moon-path’ early in Roverandom , the Tolkiens must have been at Filey during the period of the full moon, which in September 1925 began on Tuesday the 2nd. They can also be placed at Filey, more definitely, in the afternoon of Saturday, 5 September, when the north-east coast of England was struck by a terrific storm. Again John Tolkien’s memory is vivid, and it is supported by newspaper reports. The sea rose hours before the scheduled high tide, swept over the sea wall and across the promenade at Filey, devastated structures along the shore, and threw the beach into upheaval – destroying in the process any remaining hope of finding Michael’s toy. Fierce winds shook the Tolkiens’ cottage so much that they were kept awake into the night, fearing that the roof would come off. John Tolkien remembers his father telling the two older boys a story to keep them calm, and that it was at this time that he began to tell them about the dog Rover who became the enchanted toy ‘Roverandom’. The storm itself no doubt inspired the late episode in Roverandom in which the ancient Sea-serpent begins to awaken, and in so doing causes a great disturbance in the weather. (‘When he undid a curl or two in his sleep, the water heaved and shook and bent people’s houses and spoilt their repose for miles and miles around’ [ see here].)

There is no evidence that Roverandom was written down while Tolkien was at Filey. However, one of the five illustrations he made for the story, the lunar landscape reproduced in this book, is dated 1925, and it is conceivable that it was drawn at Filey during that summer. Three of the remaining illustrations for Roverandom date specifically from September 1927, while the Tolkiens were on holiday at Lyme Regis on the south coast of England: The White Dragon Pursues Roverandom & the Moondog , inscribed to John Tolkien; House Where ‘Rover’ Began His Adventures as a ‘Toy’ , inscribed to Christopher Tolkien; and the splendid watercolour The Gardens of the Merking’s Palace . On each of these is written the month and year; another drawing, of Rover arriving on the moon riding upon the seagull, Mew, is inscribed ‘1927–8’. All of these pictures are also reproduced in the present book. The evidence of the September 1927 illustrations suggests that Roverandom was retold at Lyme Regis, perhaps because the Tolkiens were once again on holiday by the sea and recalled the events at Filey only two years earlier. The inscription to Christopher Tolkien on House Where ‘Rover’ Began His Adventures as a ‘Toy’ suggests as well that Christopher was now old enough to appreciate Roverandom (he was of course only an infant in September 1925), and that the story may have been retold at least partly because he had not heard it on the previous occasion.

This apparent revival of interest in Roverandom in summer 1927 may have been the spur that led Tolkien at last to commit the story to paper; for he seems to have done so later that year, probably during the Christmas holidays. So we are inclined to think – and we can only conjecture, in the absence of dated manuscripts or other firm evidence – on the basis of two interesting (if admittedly tenuous) points. Each of these concerns the end of chapter 2 of

Читать дальше