MAGGIE PRINCE

Dedication Dedication Epigraph Map Author’s Note Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Keep Reading Acknowledgement Copyright About the Publisher

For Chris, Deborah, Daniel,and for my mother whoselandscape this is, withlove and thanks.

The northern counties from time to time had to withstand invasion by the organised forces of Scotland, but their chief embarrassment was caused by a system of predatory incursions which rendered life and property insecure.

Victoria County History of Cumberland

They have taken forth of divers families all, the very rackencrocks and pot-hooks. They have driven away all the beasts, sheep and horses…

The Silver Dale, by William Riley

On 14 April… the Scots did come… armed and appointed with gavlockes and crowes of iron, handpeckes, axes and skailinge lathers.

Border Papers, Scottish Records ii 171

Cover

Title Page Raider’s Tide MAGGIE PRINCE

Dedication Dedication Dedication Epigraph Map Author’s Note Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Keep Reading Acknowledgement Copyright About the Publisher For Chris, Deborah, Daniel,and for my mother whoselandscape this is, withlove and thanks.

Epigraph The northern counties from time to time had to withstand invasion by the organised forces of Scotland, but their chief embarrassment was caused by a system of predatory incursions which rendered life and property insecure. Victoria County History of Cumberland They have taken forth of divers families all, the very rackencrocks and pot-hooks. They have driven away all the beasts, sheep and horses… The Silver Dale, by William Riley On 14 April… the Scots did come… armed and appointed with gavlockes and crowes of iron, handpeckes, axes and skailinge lathers. Border Papers, Scottish Records ii 171

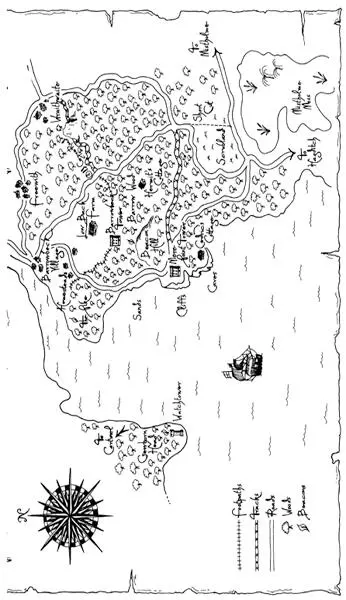

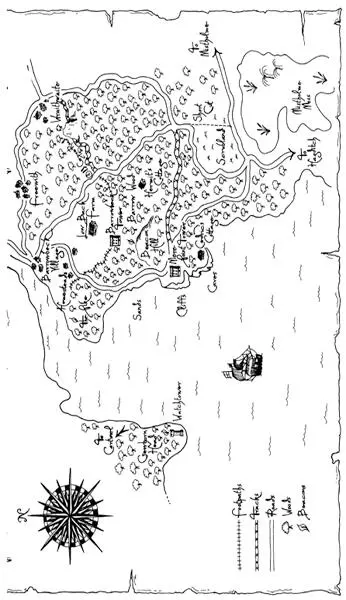

Map Map

Author’s Note In transposing Beatrice’s story into modern English,the tone and content of her original narrativehave been preserved throughout,and her exact words wherever possible. It is the late 1500s. Queen Elizabeth I is on the throne of England …

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Keep Reading

Acknowledgement

Copyright

About the Publisher

In transposing Beatrice’s story into modern English,the tone and content of her original narrativehave been preserved throughout,and her exact words wherever possible.

It is the late 1500s. Queen Elizabeth I is on the throne of England …

I jump up, jolted out of my daydream. I thought I heard voices, muttering secretively. I peer into the dimness of the woods and listen. It’s easy to start imagining things when you’re alone on the last watch of the day. On the other hand, my hearing is sharp – sharper than average – and I often hear what I am not supposed to.

I rest my hand on the haft of my knife, and creep through the swathes of pale cream daffodils to where the rough ground of the Pike slopes down towards the sea. My knife has worn through the bottom of its sheath, and keeps catching on my skirts. I shift it round to the back of me, and move out into the open where the warning beacon stands, a pile of sticks and turf in a stone trough. I can see nothing out of the ordinary, just the sun going down in the west, shining red through the beacon’s propped twigs.

We keep watch because of a very real danger. It is three years since we were last attacked by Scottish raiders, who creep round the bay in their boats or race out of the hills from the border country. Now it is spring again, the invasion season, and a watch must be kept until the first winter frosts.

The sound isn’t repeated. I suppose I’m just jumpy, for I have worse problems than Scots to think of at the moment. Light glints on fast-moving water far below me, and I sit on the edge of the beacon to watch the bore tide coming up the bay. The wind wraps my skirts round my legs and brings fine sand billowing up the slope. I push my hair back under my lace cap, and glance south along the coast to where my cousins’ pele tower stands above the sea on its limestone cliffs. The tower itself cannot be seen from here, but warning smoke from their beacon can, when necessary. Yes, there are worse things than Scots. I was sixteen last birthday, and people have begun murmuring about marriage.

This past six years, since I was no longer a child, I have known that I must marry my Cousin Hugh, as my sister must marry his brother, Gerald, to ensure preservation within the family of our two farmsteads. It had always, until now, seemed a safely distant prospect.

I stand up and make a last patrol round the slopes, kicking my way through the bracken, straining my ears for anything that is not part of the normal life of the Pike. There’s nothing, just rustlings in the undergrowth as small night creatures wake up, and the distant screaming of seagulls above the tide line. I collect my cloak from a bramble bush and set off downhill through the forest, leaving the sea behind.

It is darker here, but I see it almost at once, a rust-coloured rag hanging from the lower branches of a wych elm. I struggle through the brambles to reach it, sick already. It is warm and motionless, surprisingly solid under its soft fur, a snared squirrel, choked by the wire noose it ran through.

Perhaps this tiny tragedy was what I heard earlier. I loosen the wire and lift it down, sad little hunchback. Its red tail drifts like thistledown against my wrist. Barrowbeck villagers hunt the squirrels for their tails, which make pretty if distressing gown edgings. For a moment I do not feel in any way like a grown woman, old enough to marry. Instead I feel childlike and inadequate, not up to dealing with a world which can do this. I settle the squirrel amongst the roots of the tree and am about to cover it with last year’s dead leaves, when it twitches and blinks, then runs up the tree and is gone. It must just have had the breath knocked out of it by the noose. I laugh, relieved, feeling my heart pounding in my throat at the shock, then pick my way back to the steep path. Above me, the squirrel flickers away through the treetops. Below me, my own family’s pele tower stands in the valley on its raised shoulder of land, a foursquare limestone fortress. I make my way down the hill, more unnerved than ever now, avoiding tree roots and white rocks that poke like bones through the soil. Behind me, in the darkening woods, one late blackbird sings wildly.

In the valley I pass the stonewalled midden where Leo, our cowman, is shovelling manure. He calls out, “Evening, Mistress Beatrice!” and grins. I wave back. “’Tis a good evening for Scots,” he calls after me. I sigh, and lift the heavy iron latch of the gatehouse door. Somehow, I’m not in the mood for Leo’s wit tonight.

Читать дальше