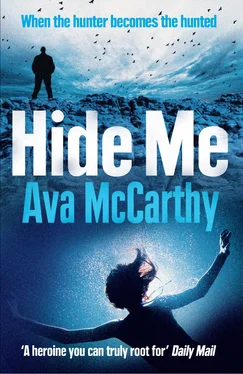

Harry continued along the wide path, inhaling the dense perfume of flowers. By now, the grandiose crypts had given way to traditional headstones, though these were still large and imposing. Most were engraved in Spanish, but some bore inscriptions in Euskara, the impenetrable language of the Basques. Language seemed to define this unique people. Ancient, complex and once-forbidden, it seemed to be the crux of who they were, along with their fervent independence. Everyone knew the Basques were fiercely proud of their identity. Harry envied them that.

‘Look, for heaven’s sake, Harry, just what is all this about?’

Harry took her time about answering, the only way she had of imposing any control. She strolled past the headstones, browsing through the names: Familia Alvarez; Familia Hernando. Eventually, she said,

‘Everybody needs to know where they come from, don’t they?’

Familia Constancio; Familia Corrales.

Miriam snorted. ‘Is that what this is about? Discovering your roots? Believe me, you can know too much about those.’ She took a quick pull on her cigarette. ‘And once you know a thing, you can’t shake it off again, either.’

Harry turned off the main path into a narrower walkway. The graves were smaller here. Many bore photographs that had been glazed on to black ceramic plaques. Harry stopped in front of one, a portrait of a silver-haired lady with a shy smile. She read the inscription:

Tu hija no te olvida. Your daughter will never forget you.

Harry blinked, aware of her throat constricting. She swallowed and moved on.

‘All I want is a sense of where Dad grew up. Where his home was, what his family was like.’ She managed a smile. ‘Who knows, I might even settle down here.’

Her mother gave a shriek of laughter. ‘Oh, God, don’t be naive, Harry. You never settle anywhere, do you?’

Harry’s cheeks burned. Miriam went on.

‘Let’s face it, fitting in just isn’t your thing, is it? You don’t have the knack. Even at home, you were always the odd one out.’ Her mother paused, and when she spoke again her tone was faintly mocking. ‘You don’t really belong anywhere, do you?’

Something shifted in Harry’s chest, something hard that ached. Suddenly she was seven years old again, lying on the floor for hours outside her mother’s room, her face pressed to the crack under the door, wondering when her mother would come outside again and talk to her.

Harry clamped her mouth shut. Jesus, she’d thought she was over all that crap. She picked up her pace, her eyes still flicking across the headstones, and aimed for an offhand tone.

‘Well, it doesn’t much matter.’ Familia Cortez; Familia Barillas. ‘For all I know, this job won’t even come off.’

‘I see. And if it doesn’t, you’ll leave San Sebastián?’

‘Maybe.’

Miriam paused, then abruptly wound up the call, as though suddenly she’d lost all interest. Harry sighed and shoved the phone back in her pocket. Stupid to have shared anything personal with her. The woman pounced on vulnerability like a hawk on a fieldmouse, and it wasn’t like Harry to let her guard down. The damn graveyard must have made her sentimental.

She continued browsing through the headstones. Familia Soliz; Familia Verano. Then her step faltered, and she felt her extremities tingle.

Familia Martinez.

Harry held her breath and moved in closer, a light buzz travelling along her arms. She scanned the most recent inscriptions, just to make sure:

Cristos Martinez, 1 Martxoa 1947 – 3 Apirila 1987

Tobias Martinez, 8 Maiatza 1971 – 3 Apirila 1987

Harry stared at the dates. Her cousin, Tobias, had died a month before his sixteenth birthday. She’d been barely seven at the time. She shook her head, fingers pressed to her lips, and scanned the older generations of her family that lay here; all long gone, and none of whom she’d ever met. The notion triggered a squeezing sensation in her chest.

Her father’s knowledge of his own ancestors was infuriatingly sketchy. He’d only lived in San Sebastián until he was ten, at which point his mother, Clara, a robust and cheerful Dubliner, had insisted on moving home in order to give her sons an Irish education.

‘At least, that’s the excuse she gave,’ Harry’s father had said, when they’d talked in Dublin a few weeks earlier. ‘If you ask me, she just wanted to escape her Basque mother-in-law.’ He’d winked at her, smiling. ‘My grandmother was a formidable woman. Aginaga, her name was. Cristos and I used to call her Dragonaga. She tried to prevent us from leaving San Sebastián, but my mother got her way in the end.’

Harry found their names on the headstone: Clara Martinez and her husband, Ramiro. Both had died before Harry was born. Far below them, she found Aginaga, who’d died at the age of ninety-four. Harry blinked. If she was reading the names and dates right, the old lady had outlived all five of her offspring. Harry felt an ache of compassion for her formidable great-grandmother. What use was longevity if it meant you saw your children die?

The only other ancestor her father remembered was his own great-grandmother, Irune. ‘She was Dragonaga’s mother-in-law. I was six when she died, and all I remember is feeling very relieved. She was terrifying. Even Dragonaga was afraid of her.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.