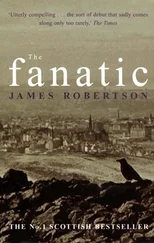

Joseph Knight

James Robertson

For Marianne

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

I: Wedderburn

Ballindean, 15 April 1802

II: Darkness

Drummossie Moor, 16 April 1746

Edinburgh, May 1746

London, June – November 1746

Kingston, January – March 1747

Glen Isla, 1760

Dundee, May 1802

Ballindean, May 1802 / Jamaica, 1760

Dundee, May 1802

Jamaica, 1762

Dundee, May 1802 / Jamaica, 1763

Ballindean, June 1802

III: Enlightenment

Edinburgh, 17 August 1773

Ballindean, August 1773

Dundee, 16 November 1773

Edinburgh, December 1773

Dundee, June 1802

Edinburgh, 30 August 1776

Dundee and Ballindean, October 1802

Ballindean, 28 November 1802

Dundee, 15 January 1803 / Edinburgh, 15 January 1778

From Mr Peter Burnet of Paisley

IV: Knight

Dundee, 24 June 1803

Wemyss, 26 June 1803

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

TO BE SOLD

A BLACK BOY, about 16 years of age, healthy, strong, and well made, has had the Measles and small pox, can shave and dress a little, and has been for these several years accustomed to serve a single Gentleman, both abroad and at home .

For further particulars inquire at Mr Gordon bookseller in the Parliament-close, Edinburgh, who has full powers to conclude a bargain .

This advertisement not to be repeated .

EDINBURGH EVENING COURANT, 28 JANUARY 1769

FOR KINGSTON IN JAMAICA

The ship MARY, JOHN MURRAY Master, now in Leith Harbour, will be ready to take in goods by the 20th September, and clear to sail by the fifth October .

For freight or passage apply to Alexander Scott Merchant in Edinburgh, or to the Master at Mrs Ritchie’s on the Shore of Leith .

EDINBURGH EVENING COURANT, 2 SEPTEMBER 1769

Ballindean, 15 April 1802

Sir John Wedderburn, tall but somewhat stooped with age, stood at the windows of his library, enjoying – as he felt he should every morning he was given grace to do so – the view to the Carse of Gowrie and the Firth of Tay. Ballindean’s policies stretched out before him: the lawn in front of the house, the little loch, then the parkland dotted with black cattle, sun-haloed sheep and their impossibly white lambs. Thick ranks of sycamore, birch and pine enclosed the house and its immediate grounds. Beyond the trees, smoke rose from the lums of estate cottages and the village of Inchture and was immediately scattered by a breeze from the east.

Had he ventured outside, Sir John could have looked behind the house, to the north, where the woods thinned out and the land rose to the sheltering Braes of the Carse. But on this morning John Wedderburn was not going anywhere – not while that wind was blowing. The view from the library was, for the time being, all he required. There might have been more majestic landscapes in Scotland, but none that could have pleased him more.

He was seventy-three, thin and angular but with rounded shoulders and a nodding, lantern-jawed face that gave him the appearance of a disgruntled horse leaning over a dyke. Strands of grey hair swept back from his forehead and curled thinly behind his ears. His brow was tanned and his cheeks weathered and taut, as if he had lived most of his life outdoors, but his hands – slender-fingered and soft – belonged more in a room such as the library.

Sunlight shafted in through the window from a watery sky. A huge fire roared and cracked in the grate at one end of the room. There were two armchairs, one on either side of the fire, and a few feet further away – close enough to get the benefit, not so close as to hurt the wood – a heavy writing-table of finest Jamaican mahogany. Near the door a wag-at-the-wa, which had just clanged out ten o’clock, ticked heavily. But it was the rows of books that dominated the room.

Bookshelves ran along two-thirds of the length of the wall behind the table, and reached almost to the ceiling. The volumes were well bound, neatly arranged, and free of dust: biography, history, philosophy, verse, those often rather too delicate creations novelles … So many books, and so little inclination left to read them. Sir John thought this without turning from the window. He felt them massing behind his back, picked them off in his mind: The Works of Ossian , heroic and Highland, whatever Dr Johnson might have said of their authenticity; Edward Long’s History of Jamaica ; Lord Monboddo’s six volumes on The Origin and Progress of Language (tedious, eccentric – Sir John had given up after half a volume); Smollett’s novels – he remembered heavy, sweltering West Indian Sundays much relieved by Peregrine Pickle and Roderick Random ; the poetical works of the ploughman poet Burns and ‘the Scotch Milkmaid’, Janet Little – little doubt already which of those would last the pace; collections of sermons, treatises on agriculture, political economy, science … And two copies of Henry Mackenzie’s Man of Feeling , because the lassies liked it so much. Sir John had once tried this book and had thrown it down in disgust – grown men bursting into tears over nothing on every third page. ‘That is not the point , Papa,’ his daughter Maria had insisted, ‘you are too matter-of-fact!’ But that was the point. There wasn’t a hard bit of fact in the entire book.

The fact was, Sir John no longer read much himself, but he subscribed to many publications, and took the lists of the Edinburgh booksellers, mainly for the benefit of his wife Alicia and his daughters. They were all there in the room too, around the fireplace, a series of silhouettes done five or six years before: Alicia, fair and delicate at forty-three; Margaret (child of his first wife – after whom she was named – now nearly thirty and so long neglected by suitors that Sir John had almost given up worrying about it); Maria, Susan, Louisa and Anne (all in their teens). Great readers, every one of them, especially of novelles and poetry. Sir John was quietly pleased that his four sons – represented in various individual and group portraits on the opposite wall, and all but the youngest sent out into the world to work – showed little inclination for reading, and none at all for novelles .

The library’s most recent acquisition, delivered the previous week, was a collection of Border ballads in two volumes, compiled by Walter Scott, Sheriff Depute of Selkirkshire. How appropriate, Sir John had thought as he cut the pages, that so many thieves and ruffians should be rounded up by a sheriff. But there was nothing really wicked in the ballads – nothing that was not safely in the rusted, misty half-dream that was Scotland’s past, nothing dangerous to the minds of his daughters. Susan was the one most easily swayed by history, romance and poor taste. But then she was female and seventeen, it was to be expected. She would grow out of it. Books might have some bad in them, but there were, after all, worse things in the world.

The last fifteen years in France had demonstrated that, but Sir John had known it much longer – since, in fact, he was Susan’s age. The French had gone quite mad, and now the world was paying for the madness. Two men born of the Revolution strode across the Wedderburn imagination, the one threatening to become a monster, the other already monstrous. Napoleon Bonaparte was the first, a brilliant Corsican soldier, who had temporarily made peace with Britain at Amiens but whose ambitions clearly pointed to further and more devastating campaigns. But worse, far worse, was the second man, the black Bonaparte, Toussaint L’Ouverture, the barbarous savage who had turned the French island colony of San Domingo – once the sugar jewel, the sparkling diadem of the West Indies – into a ten-year bloodbath. Toussaint L’Ouverture: the name passed like a cloud over the ruffled, sparkling Tay, and Sir John shuddered.

Читать дальше