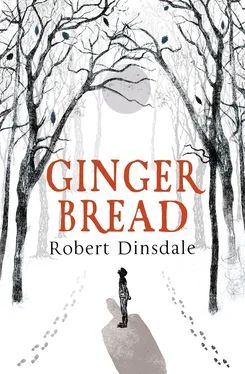

1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...20 It smells of outside, of earth and bark and crystal-clear water.

He doesn’t move until Grandfather returns, mama’s package held between hands that have lost their gloves and look raw.

‘Were you scared?’

He shakes his head.

‘I was afraid, boy, the first time I found myself in the wilderness alone.’

The boy wants to ask more, because it sounds like there’s a story in that, one quite unlike the fables Grandfather spins at night, but instead the old man tramps on and he is compelled to follow.

Before they have gone far, the trees thin, then peter out altogether. The forester’s trail turns to follow the edge of the woodland, along a ridge that overlooks a clean, white pasture. In the roots of one of the tumbled yews, there is a big yellow depression and a trail of yellow droplets running away from it.

‘Fresh!’ exclaims Grandfather, and gives a shrill, throaty cheer when he spots the tracks. ‘Roe deer. Do you see the two toes?’

He nods, even though he doesn’t. How Grandfather knows such things if he never goes to the forests, the boy cannot tell. These are the things a woodcutter might know, or a hunter or a trapper, not the things of a man pottering in his towering tenement flat. He wants to ask, but when he looks up he sees that a glassy look, as frozen as the world, is in Grandfather’s eyes. His face is haloed by the fog of his breath, and through those grey reefs he stares down the vale.

The boy’s eyes follow.

At the bottom of the pasture, nestled against another rag of woodland, there hunches a house. It is a small thing – a girl might call it dainty – but it is old and sunken and the coal shed squatting out front is collapsed, crowned with more snow and specks of black peeking through. Most of the windows aren’t glass at all, just wooden boards nailed together. There’s a chimneystack, just reaching through the snow, with bits of broken brick lying around and a wood pigeon perching on top.

‘This is it, isn’t it, papa?’

Grandfather says, ‘Did your mama ever bring you here?’

‘I think … but not like this.’

‘No?’

Sometimes, memories are like dreams. He remembers the house, but not the valley; the walls of stone, but not the ruin. In his head, it is summer. There is a cloth spread out in a wild garden ringed by forest, with the spectre of a house behind – but warm and welcoming, not frigid and alone like this thing feels. But then, he supposes, things must feel different after a death. The world is different to him, now that mama is gone, and so must be the house.

‘Are we going down?’

Grandfather sinks to his haunches. He doesn’t say a word, simply rocks on his jackboot heels, and when he draws himself back up he is changed: unwavering, resolute. He cups a hand around the back of the boy’s neck. The boy tingles. His face bursts into a grin but, when he looks up, Grandfather is still staring at the ruin, as if he can see things in the tumbledown stone and colonnades of ice that the boy cannot.

Up close, the house is more afraid than it is frightening. Like the trees, it has the face of a man. Frost along its open roof is a fringe, and the boarded windows are eyes gouged out. The door, an anguished maw, has slipped from its hinges but is fixed into place by hard-packed ice. On seeing it, Grandfather’s face is carved in the same sad lines as it was on the night he came to Yuri’s – and the boy wonders if making him come here at all is breaking that promise he made to look after him, and love him, for all time and no matter what.

‘Come on then, Vika ,’ Grandfather says, in a whisper meant only for the urn. ‘We’re home, if home this truly is.’

He heads for the door, but walks in an odd, circuitous way, first parallel to the house, then turning sharply to approach the stone. The boy scurries to join him, plunging into snow as deep as his waist, but Grandfather turns and stops him with a word. ‘Watch out. There was a garden wall.’

‘Where?’

‘Right where you’re standing. It was to keep the pigs in.’

‘Papa, how do you …’

Grandfather heaves his way to the house door. It isn’t even locked, just warped and stuck in the frame. He sets the urn down, packing the snow tightly so it doesn’t sink, and puts his shoulder to the wood. The door caves in and a tide of snow falls into the house.

Together they stand, watching the dust of ages settle in the dark passage.

‘Don’t you want to go in, papa?’

But Grandfather just looks at the black forest on the borders of the dell, the mountains in the canopy where snow and ice have crafted jagged peaks. ‘Well, boy, I’d rather be in four walls than out there.’

Grandfather takes the first step, but the boy isn’t so sure. Out here it smells clean and free, but there is something different coming from the house. It smells of dust and dark and being old.

It is only when Grandfather disappears that the boy dares to follow. First, he stands on the step and pokes his nose over the threshold. He can hear Grandfather shifting inside. There are pools of light up ahead, spilled no doubt through windows on the forested side of the house, and he sees Grandfather’s shadow flit across them. For an instant it is pitch-black; then the light returns, as Grandfather moves on.

‘Papa?’ His voice echoes, lonely as he was all day yesterday. ‘Papa?’

He creeps on. It is not, he decides, so very bad. The first step is the hardest. After that, all you’ve got to do is be brave. You’ve got to stop thinking about the smell, stop imagining all the ghosts that might live in a place like this. You’ve got to remember: you promised to look after your papa, and how can you look after him if he ventures on alone?

He reaches the doorway at the end of the hall and peeps through. Once upon a time, this was a living room. There is still an armchair in front of a big cold hearth, and a mirror on the wall covered in dust and what looks like wood-pigeon muck. On the farthest wall one of the windows is boarded up, and the other is encased in ice. Grandfather has already shuffled through another door. He can hear the old man kicking his boots in frustration.

It doesn’t feel good, going into the room. There is little carpet left, only rags around the skirting board where mice haven’t chewed it away. He can see the big wet prints left behind by Grandfather’s boots. In the middle of the room the old man must have stomped in circles, circling the armchair and then striding away.

The room on the other side is a kitchen, and that’s where Grandfather is crouched, rummaging through a cupboard. Mama sits on the countertop in her urn, and Grandfather keeps calling out to her, assuring her that he’s not really left her alone. ‘Vika,’ he says. ‘Vika, why do you drag me back here?’

The boy shuffles into the door between the living room and kitchen. It is lighter in here, because more light can pour through the backdoor. The glass is coated in ice, but it is less thick on this side of the house and, if you squint, you can even make out what used to be a garden, with a chicken coop and rabbit hutch and vegetable patch with a low stone wall.

Grandfather is down on his knees, buried in a cupboard under the sink. There are things scattered around his knees: old gloves, the handle of a trowel, a terracotta plot, a clod of earth.

‘What are you looking for?’

Grandfather rears up with a sudden flourish: in his hands a single-headed, dark axe. His gnarled fingers are so tight around the handle that they look as knotted as the wood.

‘Papa!’

The old man’s eyes are raw, but he is smiling, his mouth full of gaps. ‘We’ll need kindling.’

‘Kindling?’

‘To kindle a fire.’

‘How do you kindle a fire?’

Читать дальше