As I came of age in postwar America, the search for identity was assuming Holy Grail status, particularly for middle-class Americans seeking purchase in the new suburban sprawl. By the ’70s, “finding yourself” was the vaunted magic key, the portal to psychic well-being. In my own suburban town in Westchester County, it sometimes felt as if everyone I knew, myself included, was seeking guidance from books with titles like Quest for Identity , Self-Actualization , Be the Person You Were Meant to Be . Our teen center sponsored “encounter groups” where high schoolers could uncover their inner selfhood; local counseling services offered therapy sessions to “get in touch” with “the real you”; mothers in our neighborhood held consciousness-raising meetings to locate the “true” woman trapped inside the housedress. Liberating the repressed self was the ne plus ultra of the newly hatched women’s movement, as it was the clarion call for so many identity movements to follow. To fail in that quest was to suffer an “identity crisis,” the term of art minted by the reigning psychologist of the era, Erik Erikson.

But who is the person you “were meant to be”? Is who you are what you make of yourself, the self you fashion into being, or is it determined by your inheritance and all its fateful forces, genetic, familial, ethnic, religious, cultural, historical? In other words: is identity what you choose, or what you can’t escape?

If someone were to ask me to declare my identity, I’d say that, along with such ordinaries as nationality and profession, I am a woman and I am a Jew. Yet when I look deeper into either of these labels, I begin to doubt the grounds on which I can make the claim. I am a woman who has managed to bypass most of the rituals of traditional femininity. I didn’t have children. I didn’t yearn for maternity; my “biological clock” never alarmed me. I didn’t marry until well into middle age—and the wedding, to my boyfriend of twenty years, was a spur-of-the-moment affair at City Hall. I lack most domestic habits—I am an indifferent cook, rarely garden, never sew. I took up knitting for a while, though only after reading a feminist crafts book called Stitch ’n Bitch .

I am a Jew who knows next to nothing of Jewish law, ritual, prayers. At Passover seders, I mouth the first few words of the kiddush—with furtive peeks at the Haggadah’s phonetic rendition and only the dimmest sense of the meaning. I never attended Hebrew school; I wasn’t bat mitzvahed. We never belonged to the one synagogue in Yorktown Heights, which, anyway, was so loosey-goosey Reform it might as well have been Unitarian. I’m not, technically speaking, even Jewish. My mother is Jewish only on her father’s side, a lack of matrilineage that renders me gentile to all but the most liberal wing of the rabbinate.

So if my allegiance to these identities isn’t fused in observance and ritual, what is its source?

I am a Jew who grew up in a neighborhood populated with anti-Semites. I am a woman whose girlhood was steeped in the sexist stereotypes of early ’60s America. My sense of who I am , to the degree that I can locate its coordinates, seems to derive from a quality of resistance, a refusal to back down. If it’s threatened, I’ll assert it. My “identity” has quickened in those very places where it has been most under siege.

My neighborhood in Yorktown Heights was staunchly Catholic, mostly second-generation Irish and Italian, families who were one step out of the Bronx and eager to pull up the drawbridge against any other ethnicities or religions—in particular, blacks and Jews. In the mid-’60s, when a petition circulated to block a black family from buying a home on the street, my mother squared off against the petitioners. The family eventually bought the house; my mother remained the neighborhood pariah. Soon after we arrived, a boy down the street welcomed me by hurling rocks while yelling, “You’re a kike!” How he knew was a mystery: we’d shown no signs, and wouldn’t. My father made sure we aggressively celebrated Christmas and Easter and sent out holiday cards with Christian images (The Little Drummer Boy, Little Jesus in the Manger …). His eagerness to pass only reinforced my sense of grievance and, perversely, my commitment to an identity I barely understood. You could say that my Jewishness was bred by my father’s silence.

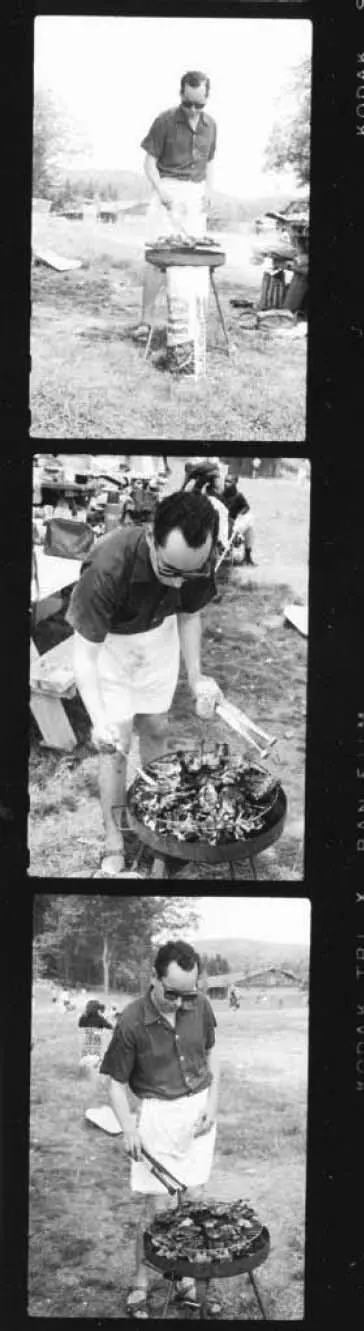

And my womanhood bred by my mother’s despair. When she gave up her job in the city (as an editor of a life-insurance periodical) and moved to the suburbs, my father awarded her the various accessories to go with her newly domesticated state: a dust mop, a housedress, hot rollers, a bouffant wig (with Styrofoam head stand, on which the hairpiece was left to languish), and a box of stationery printed with a new name that heralded the erasure of hers, “Mrs. Steven C. Faludi.” No doubt I learned some of my anti-nesting tendencies from my mother in this time. My father, for his part, was eager to present himself as a model of postwar American manhood, with wife and children as supporting cast, along with the convertible sports car (and before that, a Lincoln Continental), the saws and drills in the basement, the barbeque grill, the cigar boxes and pipe on the mantel, and the oversized armchair with a headrest in the living room that we all understood to be “his.” The chair was his throne, proof of his dominion and dominance over his quarter-acre crabgrass demesne. We were careful not to sit in it.

When I was in grade school, my father bought me a tabletop weaving loom. After a halfhearted effort that produced a couple of uneven fabric coasters and one miniature scarf, I took the loom off my desk and stashed it in the closet—to make room for my writing pads. Journalism was my calling from an early age. I perceived it, specifically, as something I did as a woman , an assertion of my female independence. I worked my way through stacks of library books on intrepid “girl reporters” and imagined myself in the role of various crusading female journalists, fictional and real, Harriet the Spy and His Girl Friday ’s Hildy Johnson, Ida B. Wells and Ida Tarbell. In my schoolgirl fantasies, the incarnation of heroic womanhood was Nellie Bly exposing the horrors of Blackwell Island’s asylum for women, Martha Gellhorn infiltrating D-Day’s all-male press corps (and one-upping her war-correspondent husband, Ernest Hemingway). On the Little Red Riding Hood stage that my father had built, I turned the girl in the red cape into an investigative reporter uncovering the crimes of a wolf who was now the Big Bad Warmonger (it was the Nixon years). By fifth grade, I was championing my causes in my elementary school newspaper—for the Equal Rights Amendment and legal abortion—incurring the wrath of the John Birch Society, whose members denounced me before the school board as a propagator of loose morals and a “pinko Commie fascist.” The denunciations made me all the more a journalist, my sense of selfhood affirmed as that-in-my-makeup-that-someone-else-opposed. And all the more a defender of my gender. I asserted my fealty to women through my reportorial diatribes against the canon of womanly convention. I renounced the standards of femininity not to renounce my sex but to declare it. In short, I became a feminist.

That identity became explicit the day my teenaged self consumed Marilyn French’s The Women’s Room . I read that overwrought fulmination against suburban marriage in one sitting, shortly after my now-divorced mother had fled suburbia with her two children, resettling in a cramped two-bedroom apartment in the East Village in New York. But more accurately, my feminist consciousness emerged a season earlier, following a bloody night in a suburban house in 1976, seeing my mother unjustly demoted to “fallen” woman and my father falsely elevated to defender of home and hearth. I would spend the next many decades writing about the politics of women’s rights, always at that one remove of journalistic observer. My subject was feminism on the public stage, in the media and popular culture, legislative halls and corporate offices. But I never forgot its provenance: this was personal for me.

Читать дальше