Published by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

The News Building

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by HarperCollins Publishers 2017

Copyright © Susan Wiggs 2017

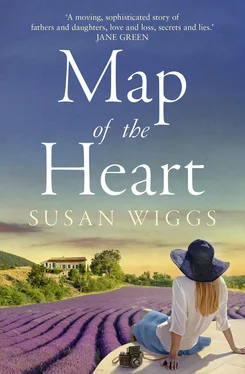

Cover design and illustration by Alan Dingman © HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2017

Susan Wiggs asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008151324

Ebook Edition © August 2017 ISBN: 9780008151331

Version: 2017-09-28

For my husband, Jerry: For all the journeys we’ve made, for all the moments of inspiration, for getting lost on lost byways, for endless rambles and flights of imagination, for knowing that the greatest journey in life is the one that takes you home. You’re the best adventure I’ve ever had.

Contents

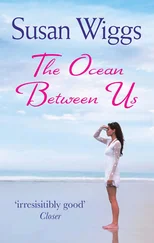

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Part 1: Bethany Bay

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Part 2: The Var

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Part 3: Bethany Bay

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Part 4: Bellerive

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Part 5: Aix-en-Provence

Chapter Seventeen

Part 6: The Var

Chapter Eighteen

Part 7: Switchback

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Susan Wiggs

About the Publisher

Thank you for all the Acts of Light which beautified a summer now passed to its reward.

—LETTER FROM EMILY DICKINSON TO MRS. JOHN HOWARD SWEETSER

Of the five steps in developing film, four must take place in complete darkness. And in the darkroom, timing was everything. The difference between overexposure and underexposure sometimes came down to a matter of milliseconds.

Camille Adams liked the precision of it. She liked the idea that with the proper balance of chemicals and timing, a good result was entirely within her control.

There could be no visible light in the room, not even a red or amber safelight. Camera obscura was Latin for “dark room,” and when Camille was young and utterly fascinated by the process, she had gone to great lengths to practice her craft. Her first darkroom had been a closet that smelled of her mom’s frangipani perfume and her stepdad’s fishing boots, crusted with salt from the Chesapeake. She’d used masking tape and weather stripping to fill in the gaps, keeping out any leaks of light. Even a hairline crack in the door could fog the negatives.

Found film was a particular obsession of hers, especially now that digital imagery had supplanted film photography. She loved the thrill of opening a door to the past and being the first to peek in. Often while she worked with an old roll of film or movie reel, she tried to imagine someone taking the time to get out their camera and take pictures or shoot a movie, capturing a candid moment or an elaborate pose. For Camille, working in the darkroom was the only place she could see clearly, the place where she felt most competent and in control.

Today’s project was to rescue a roll of thirty-five-millimeter film found by a client she’d never met, a professor of history named Malcolm Finnemore. The film had been delivered by courier from Annapolis, and the instructions inside indicated that he required a quick turnaround. Her job was to develop the film, digitize the negatives with her micrographic scanner, convert the files into positives, and e-mail the results. The courier would be back by three to pick up the original negatives and contact sheets.

Camille had no problem with deadlines. She didn’t mind the pressure. It forced her to be clearheaded, organized, in control. Life worked better that way.

All her chemicals waited in readiness—precisely calibrated, carefully measured into beakers, and set within reach. She didn’t need the light to know where they were, lined up like instruments on a surgeon’s tray—developer, stop bath, fixer, clearing agent—and she knew how to handle them with the delicacy of a surgeon. Once the film was developed, dried, and cured, she would inspect the results. She loved this part of her craft, being the revealer of lost and found treasures, opening forgotten time capsules with a single act of light.

There were those, and her late husband, Jace, had been among them, who regarded this as a craft or hobby. Camille knew better. One look at a print by Ansel Adams—no relation to Jace—was proof that art could happen in the darkroom. Behind each finished, epic print were dozens of attempts until Adams found just the right setting.

Camille never knew what the old film would reveal, if it hadn’t been spoiled by time and the elements. Perhaps the professor had come across a film can that had been forgotten and shoved away in the Smithsonian archives or some library storage room at Annapolis.

She wanted to get this right, because the material was potentially significant. The roll she was carefully spooling onto the reel could be a major find. It might reveal portraits of people no one had ever seen before, landscapes now changed beyond recognition, a rare shot of a moment in time that no longer existed in this world.

On the other hand, it might be entirely prosaic—a family picnic, a generic street scene, awkward photos of unidentifiable strangers. Perhaps it might yield pictures of a long-gone loved one whose face his widow longed to see one more time. Camille still remembered the feeling of pain-filled joy when she’d looked at pictures of Jace after he’d died. Her final shots of him remained in the dark, still spooled in her camera. The vintage Leica had been her favorite, but she hadn’t touched it since the day she’d lost him.

Working with film from complete strangers suited her better. Only last week, a different storage box had yielded a rare collection of cellulose-nitrate negatives in a precarious state. The images had been clumped together, fused by time and neglect. Over painstaking hours, she had teased apart the film, removing mold and consolidating the image layers to reveal something the camera’s eye had seen nearly a century before—the only known photograph of a species of penguin that was now extinct.

Another time, she had exposed canned negatives from a portrait session with Bess Truman, one of the most camera-shy first ladies of the twentieth century. To date, the project that had gained the most attention for Camille had been a picture of a murder in commission, posthumously absolving a man who had gone to the gallows for a crime he hadn’t committed. Write-ups in the national press gave her credit for solving a long-standing mystery, but Camille considered the achievement bittersweet, knowing an innocent man had hanged for a crime while the murderer had lived to a ripe old age.

Читать дальше