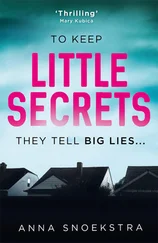

ANNA SNOEKSTRAwas born in Canberra, Australia in 1988. She studied Creative Writing and Cinema at Melbourne University, followed by Screenwriting at RMIT University.

She currently lives in Melbourne with her husband and tabby cat.

For my mother.

Contents

Cover

About the Author ANNA SNOEKSTRA was born in Canberra, Australia in 1988. She studied Creative Writing and Cinema at Melbourne University, followed by Screenwriting at RMIT University. She currently lives in Melbourne with her husband and tabby cat.

Title Page

Dedication For my mother.

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Acknowledgements

Copyright

I’ve always been good at playing a part: the mysterious seductress for the sleazebag, the doe-eyed innocent for the protector. I had tried both on the security guard and neither seemed to be working.

I’d been so close. The supermarket doors had already slid open for me when his wide hand clamped on my shoulder. The main road was only fifteen paces away. A quiet street lined with yellow-and-orange-leaved trees.

His grip tightened.

He brought me into the back office. A small cement box with no windows, barely big enough to fit the old filing cabinet, desk and printer. He took the bread roll, cheese and apple out of my bag and laid them on the table between us. Seeing them spread out like that gave me a jolt of shame, but I tried my best to hold his eye. He said I wasn’t going anywhere until I gave him some identification. Luckily, I had no wallet. Who needs a wallet when you don’t have any money?

I attempted all my routines on him, letting tears flow when my insinuations fell flat. It wasn’t my best performance; I couldn’t stop looking at the bread. My stomach was beginning to cramp. I’ve never felt hunger like this before.

I can hear him now, talking to the police on the other side of the locked door. I stare up at the notice board above the desk. This week’s staff roster is there, alongside a memo about credit card procedures with a smiley face drawn on the bottom and a few photographs from a work night out.

I have never wanted to work in a supermarket. I’ve never wanted to work anywhere, but all of a sudden, I’m painfully jealous.

“Sorry to bother you with this. Little skank won’t give me any ID.”

I wonder if he knows I can hear him.

“It’s all right—we’ll take it from here.” Another voice.

The door opens and two cops look in at me. It’s a female and a male, both probably about my age. She has her dark hair pulled back in a neat ponytail. The guy is pasty and thin. I can tell straightaway that he’s going to be an asshole. They sit down on the other side of the table.

“My name is Constable Thompson and this is Constable Seirs. We understand that you were caught shoplifting from this store,” the male cop says, not even bothering to hide the boredom in his tone.

“No, actually, I wasn’t,” I say, imitating my stepmom’s perfect breeding. “I was on my way to the register when he grabbed me. That man has a problem with women.”

They look at me doubtfully, their eyes sliding over my unwashed clothes and greasy hair. I wonder if I smell. My bruised and swollen face isn’t doing me any favours. It was probably why I got caught in the first place.

“He was calling me foul names when he brought me back here—” I lower my voice “—like skank and whore . Disgusting. My father is a lawyer and I expect he’ll want to sue for misconduct when I tell him what went on here today.”

They look at each other and I can immediately tell they don’t buy it. I should have cried.

“Listen, honey, it’s going to be fine. Just give us your name and address. You’ll be back home by the end of the day,” the girl cop says.

She is my age and she’s calling me pet names like I’m just a kid.

“The other option is that we book you now and take you back to the station. You’ll have to wait in a cell while we sort out who you are. It will be a lot easier if you just give us your name now.”

They’re trying to scare me and it’s working, but not for the reason they think. Once they have my fingerprints it won’t take them long to identify me. They’ll find out what I did.

“I was so hungry,” I say, and the tremor in my tone isn’t fake.

It’s the look in their eyes that does it. A mix of pity and disgust. Like I’m worth nothing, just another stray for them to clean up. A memory slowly opens and I realize I know exactly how to get myself out of this.

The power of what I’m about to say is huge. It courses through my body like a shot of vodka, removing the tightness in my throat and sending tingles to the tips of my fingers. I don’t feel helpless anymore; I know I can pull this off. Staring at her, then him, I let myself savor the moment. Watching them carefully to enjoy the exact instant their faces change.

“My name is Rebecca Winter. Eleven years ago, I was abducted.”

1

2014

I sit in an interview room with my face down, holding my coat tightly around myself. It’s cold in here. I’ve been waiting for almost an hour, but I’m not worried. I imagine what a stir I’ve caused on the other side of that mirror. They’re probably calling in the missing persons unit, looking up photographs of Rebecca and painstakingly comparing them to me. That should be enough to convince them; the likeness is uncanny.

I saw it months ago. I was wrapped up with Peter, a little bundle of warmth. Usually I got teary when I was hungover and just spent the day hiding in my room listening to sad music. It was different with him. We woke up at noon and sat on the couch all day eating pizza and smoking cigarettes until we started feeling better. That was back when I thought my parents’ money didn’t matter and all I needed was love.

We were watching some stupid show called Wanted . They were talking about a string of grisly murders at a place called Holden Valley Aged Care in Melbourne and I started looking for the remote. Butchered grannies were definitely a mood killer. Just as I went to change the channel, the next story began and a photograph came up on the screen. She had my nose, my eyes, my copper-coloured hair. Even my freckles.

“Rebecca Winter finished her late shift at McDonald’s, in the inner south Canberra suburb of Manuka, on the seventeenth of January 2003,” a man said in a dramatic voice over the photograph, “but somewhere between her bus stop and home she disappeared, never to be seen again.”

“Holy shit, is that you?” Peter said.

The girl’s parents appeared, saying their daughter had been missing for over a decade but they still had hope. The mother looked like she was about to cry. Another photograph: Rebecca Winter wearing a bright green dress, her arm slung around another teenage girl, this one with blonde hair. For a foolish moment, I tried to remember if I had ever owned a dress like that.

A family portrait: the parents looking thirty years younger, two grinning brothers and Rebecca in the middle. Idyllic. They may as well have had a white picket fence in the background.

Читать дальше