‘Yes, M’sieu.’

‘Do you understand the risks involved – great risks?’

‘Yes, M’sieu.’

‘And you know how to keep your tongue, do you?’

‘Absolutely, M’sieu.’

‘OK. Go to the Fontaine halt on the tramway which takes you up to Villard at five o’clock tomorrow evening. Ask for one of the Huillier brothers and tell him discreetly that you have come to see “Casimir” – that’s the password. He will tell you what to do next. Follow his instructions closely and without any questions. Take a rucksack with what you need. But be careful. Don’t take too much. You must look like a casual traveller.’

The young man nodded and left the room, closing the door behind him.

Eugène Chavant took out a small piece of paper and wrote a message for his friend Jean Veyrat: ‘There will be one colis [package] to take up to Villard tomorrow evening.’

The following evening a Huillier bus set the young man down in the main square of the town of Méaudre on the northern half of the Vercors plateau. Here, following his instructions, he went to a café in one of the town’s back streets where he found he was among a number of young men who likewise seemed to be waiting for something – or someone. A short time later an older man arrived. He was wearing hiking clothes and boots and carried a small khaki rucksack.

‘Follow me,’ he said, and led the way out of the café and into the darkness.

The little group walked north along back roads for forty minutes or so and then took a short break before starting to climb steeply up the mountain. Half an hour later they entered a forest and five minutes after that their guide stopped in the darkness and gave three low whistles. Out of the night came three answering whistles. A guide emerged from the trees and led the little group of newcomers to a shepherd’s hut in a clearing in the forest. Though it is doubtful that any of them realized it, they had all taken an irreversible step out of normality, into the Maquis and a life of secrecy and constant danger. One way or another, their lives would never be the same again.

As German demands for manpower increased, the trickle of réfractaires turned into a flood. The numbers at the Ambel farm quickly rose to eighty-five. There was no more space. In Eugène Samuel’s words, ‘The young men coming up the mountain became more and more numerous. Now it was not just the specialists who were being called away, but whole annual intakes of young men whom Laval wanted to send to help Hitler’s war effort. There was a mood of near panic among the young men, and the resources of the Gaullist resistance organizations were very soon swamped. We needed new camps; we needed more financial resources; we needed food; we needed clothes and above all we needed boots. We needed to organize some kind of security system to search out the spies who we knew the Milice were infiltrating with the réfractaires . We needed arms.’

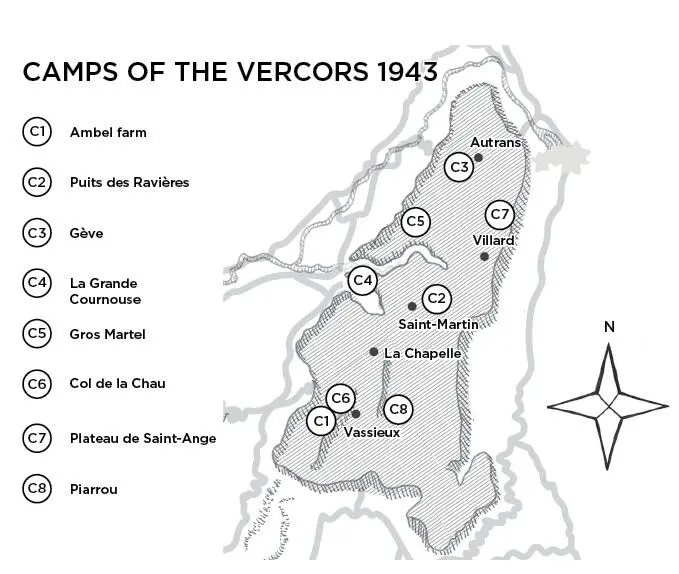

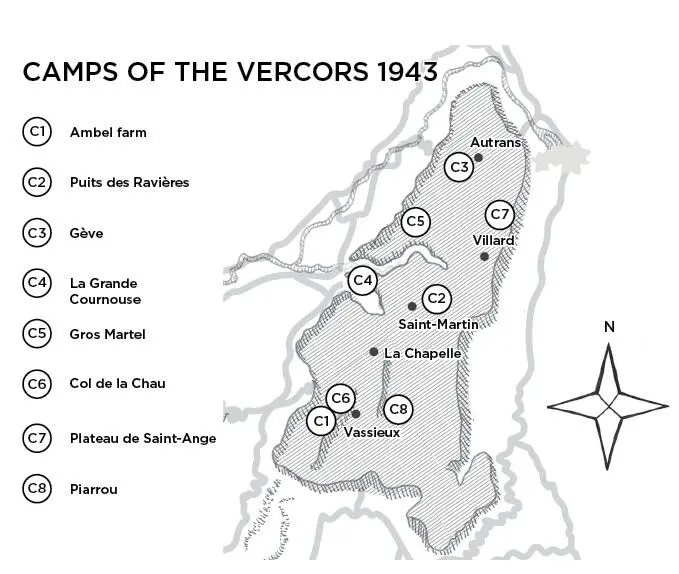

New camps were soon found. And not just in the Vercors. Elsewhere in the region, other early Resistance groups were also establishing camps for fleeing réfractaires in the remote areas of the nearby Chartreuse Massif and the Belledonne and Oisans mountain ranges which bordered the Grésivaudan valley. Between February and May 1943, eight new réfractaire camps – housing some 400 men in all and numbered consecutively from Ambel (C1) – were established across the Vercors plateau under the direction of Aimé Pupin. To this total must be added two military camps, one set up in May by an ex-Military School in Valence, another established in November under the control of Marcel Descour.

Map 3

Those who joined the camps between March 1943 and May 1944 (that is before the Allied landings in Normandy) were of differing ages and came from a wide area. In a sample of forty-four réfractaires in the initial influx between March and May 1943, almost half were over thirty years old, many of them married. As might be expected, the majority (60 per cent) were from the immediate locality (the region of Rhône-Alpes), but among the rest almost 10 per cent were Parisians, a further 10 per cent were born out of France and nearly 15 per cent came from the eastern regions of France. There was similar diversity when it came to previous employment. In C3, above Autrans, nearly half the camp members had been ordinary workers, almost a third technicians of one sort or another, some 12 per cent were students and nearly 10 per cent had been regular soldiers. Politically, too, there was a broad variety of opinions and views. The fact that the great majority of the Vercors’ civilian camps were loyal to de Gaulle meant that the organized presence of the Communists and the French far right was almost non-existent on the plateau. Individually, however, the camps included adherents to almost every political belief (except of course fascism). Political discussions round evening campfires were frequent, varied and at times very lively.

By autumn 1943, every community of any size on the plateau had a secret camp of one sort or another near by – and every inhabitant on the plateau would have been aware of the unusual nature of the new young visitors in their midst. For Samuel, Pupin, Chavant and their colleagues, the administrative burden of all this was immense. Pupin later said: ‘We didn’t have a moment of respite. Our eight camps occupied our time fully.’ The biggest problem by far, however, was finding the money to pay for all this. Collections were made among family, well-wishers and workplaces – two Jewish men contributed between them 20,000 francs a week which they had collected from contacts. But it was never enough.

London started providing huge subventions to support the réfractaire movement. During Jean Moulin’s visit to London in February 1943, de Gaulle charged him with ‘centralizing the overall needs of the réfractaires and assuring the distribution of funds through a special organization, in liaison with trades unions and resistance movements’. On 18 February, Farge delivered a second massive subvention amounting to 3.2 million francs to be used for Dalloz’s Plan Montagnards alone. And on 26 February Moulin’s deputy sent a coded message to London containing his budget proposals for March 1943. This amounted to a request for no less than 13.4 million francs for all the elements of the Resistance controlled by de Gaulle, of which some 1.75 million francs per month was designated for the Vercors. This was in addition to the private donations pouring into Aimé Pupin’s coffers by way of a false account in the name of a local beekeeper, ‘François Tirard’, at the Banque Populaire branch in Villard. This level of support made the Vercors by far the biggest single Resistance project being funded by London at this point in the war.

Despite these significant sums, money remained an ever-present problem for those administering the Vercors camps through 1943 and into the following year. A British officer sent on a mission to assess the strength and nature of the Maquis in south-eastern France visited the Vercors later in 1943 and reported that those in the camps ‘have to spend much of their time getting food etc. They have to do everything on their own and are often short of money. In one case they stole tobacco and sold it back onto the Black Market to get money.’

Not surprisingly this kind of behaviour, though by no means common, caused tensions between the réfractaires and local inhabitants. With food so short, the proximity of groups of hungry young men to passing flocks of sheep proved to be an especially explosive flash-point. On 14 June 1943, the réfractaires of Camp C4, fleeing to avoid a raid on their camp by Italian Alpine troops, arrived on the wide mountain pasture of Darbonouse where they were met by a flock of sheep numbering some 1,500. Their commander told them: ‘If there is any thieving I will take the strongest measures against the perpetrators. Remember that it is in our interests to make the shepherds our friends. Remember too that it is through our behaviour that the Resistance is judged.’

Читать дальше