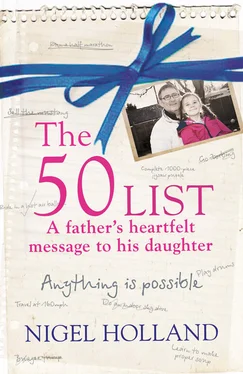

For my darling wife, Lisa, and my wonderful children, Mattie, Amy and Ellie: with you beside me, I know anything is possible Thanks also to my brothers, Mark and Gary, and my sister, Nicola: your love and support means everything to me Finally, dear Mum and Dad: thanks for everything ‘All men dream, but not equally. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds, wake in the day to find that it was vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act on their dreams with open eyes, to make them possible.’ T. E. LAWRENCE CONTENTS Cover CONTENTS Cover Title Page Dedication Epigraph Introduction SEPTEMBER NOVEMBER DECEMBER FEBRUARY MARCH APRIL MAY JUNE JULY AUGUST SEPTEMBER OCTOBER NOVEMBER DECEMBER Epilogue The 50 List My Comedy Sketch Picture Section Acknowledgements Copyright About the Publisher

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Introduction

SEPTEMBER

NOVEMBER

DECEMBER

FEBRUARY

MARCH

APRIL

MAY

JUNE

JULY

AUGUST

SEPTEMBER

OCTOBER

NOVEMBER

DECEMBER

Epilogue

The 50 List

My Comedy Sketch

Picture Section

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

Just like any parent, I want the best for my children. I want them to feel safe, to be confident and to grow up with the understanding that life is to be challenged: to be explored and enjoyed, no matter what obstacles you might have to face. My wife and I have three great children and I am very proud of them. The two eldest, Matthew (15) and Amy (13), have grown up with responsibilities that most of their peers have never experienced. I am in a wheelchair, and being a wheelchair-using dad limits me from doing some of the things that other dads do, like football and cycling – activities that other parents take for granted. But their understanding of the issues I face makes the relationship I have with my children what it is: close, loving and, most of all, fun. They are growing up to be caring and thoughtful individuals with an empathy that belies their ages.

Ten years ago my wife, Lisa, gave birth to our youngest daughter, Eleanor. She has been diagnosed with the same condition that I have: Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) or peroneal muscular atrophy, also known as hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy. What this means in practical terms is that there is wastage of the muscles in the lower part of the limbs. I can no longer walk and my hand strength is very weak, limiting my dexterity. Ellie is walking still but her gait – the way she walks – is affected. In 2010 she had to undergo surgery on her legs to try to straighten her ankles, as her tendons were pulling her feet inwards. The disability can affect people in many different ways.

Both my wife and I want to see Ellie enjoy life just as much as her older siblings and we are aware that she will face problems as she grows up, but what we want her to understand is that those problems can be overcome. In my life I have done many crazy and wonderful things that many people thought were beyond my capabilities: water-skiing, off-road 4x4, go-karting, gliding, diving – the list goes on. I even played drums in a band in the 1980s, reaching the dizzy heights of playing the Hippodrome at Leicester Square. Up until 2010 I was competing in the National Drag Racing Championships in a powerful Ford Mustang race car. I’ve never let anything stop me from realizing my dreams, so I want Ellie to know that her capabilities are to be explored. And it’s not just that there’s nothing wrong with ‘having a go’, either. It’s that you’ll never know what you can do till you try.

Then, one day, not so long ago, something else struck me: that there’s a saying – or, more correctly, an idiom – that we all know, which goes ‘actions speak louder than words’. And as soon as it occurred to me, that was it; I was away. I wouldn’t just tell her. I would show her.

Nigel Holland, December 2012

‘Dad,’ Ellie says to me, ‘you’re mad.’

‘Well, you knew that already,’ I say, grinning at the look of incomprehension on her face as she works her way down the piece of paper in her hand. It is a list. A list of all the crazy things I plan to do over the coming months. I can tell they’re crazy just by looking at the expression on her face.

‘Yeah, I know, Dad,’ she says, ‘but this is a big list. How are you going to do everything on it in one year?’

‘I’m going to be doing even more than that,’ I correct her. ‘Because it’s not finished yet. I was hoping you could suggest some things to put on it too.’

She looks again, her slender index finger tracing a line down the page. It’s actually two lists, one marked ‘extreme’ and one marked ‘other’. Ellie points to an item marked ‘extreme’.

‘What’s this?’ she asks.

‘Zorbing?’ I say, reading it. ‘Oh, it’s great fun. It’s rolling down a hill inside a very large bouncy ball.’

She takes this in, and her look of incomprehension doesn’t change. Though I’ve tried to explain to Ellie the main reason why I’m doing this – to inspire her – Ellie has a learning difficulty, which means she doesn’t always get the bigger picture. But perhaps she doesn’t need to. Not now, at least. All I really want is that she gets caught up in the excitement and thinks ‘can’ rather than ‘can’t’. That’ll be good enough for me. Though, hmm, ‘zorbing’ – she’s probably right: I am mad.

It’s late in the afternoon, the watery late-September sun is almost gone now, and we’re contemplating what seemed like a brilliant idea when I first thought of it, but which now seems to mark me out as bonkers: a list of 50 challenges, of all kinds, to be completed within the year, to prove that a) you really can do almost anything that you put your mind to and b) turning 50 doesn’t spell the end of any sort of life other than the pipe-and-slippers kind.

Because that’s what had struck me a couple of weeks earlier when a work colleague had mentioned my upcoming 50th birthday, saying that 50 – the big 50 – was a particularly depressing milestone. One that marked the end of youth and the beginning of ‘being old’, which was something I was not prepared to be. ‘And your point?’ I’d retorted, rising swiftly to the bait. ‘I don’t mind getting old, but I refuse to grow up.’ It was a thought – and a mindset – that had stayed with me all day.

And here we were, the idea having not only taken root but also sprouted. And what had started as a whimsical, unfocused kind of wish list had somehow become a full-blown plan. A plan to prove something to both myself and my children – particularly my youngest, ‘disabled’ daughter.

‘OK,’ I say to Ellie. ‘ You think of some challenges.’

She considers it for a few seconds, chewing thoughtfully on her lower lip. ‘Erm, maybe jump over a tall building?’ she offers finally. And I’m pretty sure she’s only half joking.

Which is nice – it’s always good to be your children’s superhero – but her idea is not do-able. Even for me. I say so.

‘What about flying, then?’ she says.

‘What, you mean as in a plane?’

‘No,’ she retorts, in all seriousness. ‘Like Superman!’

Silly me. I should have known. Of course she means like Superman. I am her hero, just the same way my dad was my hero. It’s almost 30 years now since I lost him – over half a lifetime. And I still can’t believe he’s never coming back.

‘Ah,’ I tell Ellie, ‘there’s a problem with that one. I don’t have any red underpants that will fit over my trousers.’