THE PERILS OF THE PUSHY PARENTS

THE PERILS OF THE PUSHY PARENTS

A CAUTIONARY TALE

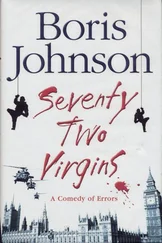

Written and illustrated by

BORIS JOHNSON

I

The nicest kids you ever saw

Were Jim and Molly Albacore,

Who seldom made a naughty noise

Or screamed for more expensive toys.

Indeed, they hardly ever cried,

Except when once a hamster died.

If they fought they made it up,

And if they broke a plate or cup,

They’d both confess at once and say,

‘I think we’ve saved enough to pay!’

They brushed their teeth and scrubbed their toes.

They very rarely picked their nose,

And kept each other free of nits

By using little grooming kits.

In summer from the peep of dawn

They gambolled on the tiny lawn

In scenes of perfect bourgeois ease

With lavender and bumblebees

And games involving bits of string

Or planks of wood, or anything.

And yet, of course, when winter came,

The garden wasn’t quite the same.

At dusk and having time to kill

What they liked to do was chill,

And get some lovely sliced white bread,

Then smear it thick with peanut spread,

Then cover that with strawberry jelly

And scoff it all before the TELLY.

Oh, how they loved that warm machine,

Its friendly, wise, hypnotic screen.

It never moaned at them or swore

Or yelled at them to shut the door.

Or taught them long division sums

Or told them not to scratch their bums

Or asked them in that maddening way,

‘Darling, what did you DO today?’

Oh no, their television set

Would never carp at them or fret,

But delved into its mighty brain

To give, and give, and give again.

It gave them Friends and Dr Who

And dancing comps and Scooby Doo,

And wacky gameshows from Japan

In which contestants take a flan

Or piece of pie, and shout ‘Banzai’,

And chuck it in the other’s eye,

So provoking gales of mirth

From all the children of the earth.

It gave them lumps of TV fun,

Baked and sweetened, every one,

Edible, digestible,

And slowly irresistible.

Sometimes when the coast was clear

They’d plug the console in the rear,

And play without a hint of shame

The latest electronic game.

Did anything detract from this

Condition of domestic bliss?

Was there a thorn, was there a weed in

Jim and Molly’s childhood Eden?

There was. I crave your kind forbearance:

It’s time to talk about the PARENTS.

II

The source, my friends, of half life’s trouble

Is seeking reputation’s bubble,

And though the kids were not ambitious –

Their beds were soft, their food delicious –

Their lives were not entirely cushy:

Their parents were so very pushy.

When they looked on Jim and Molly

(I say this with some melancholy)

They missed the pair of happy moochers

And saw a brace of ‘brilliant futures’.

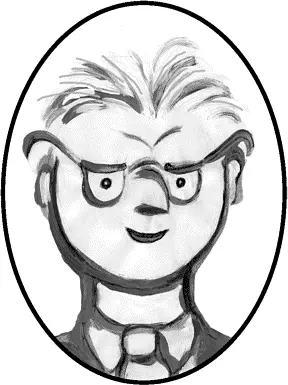

Let’s take the father. What a freak!

His balding brow and lean physique

Concealed a terrifying zest

For putting children to the test.

When they were babies in the womb

He’d read them Berkeley, Locke and Hume.

Before their eyes were even open

He’d hum them bits of Bach and Chopin,

And not content, this massive swot,

Would teach them physics in the cot

And swipe away their infant bottle

And fill their hands with Aristotle.

When normal kids are doing well

To stick a bit of pasta shell

On card, or play with coloured blocks

He taught them Zeno’s paradox!

Every year it grew intenser:

At five he put them down for Mensa.

At six he made them, lass and lad,

Contest a maths Olympiad

Which venture meeting mixed success

He’d wake them up with cries of ‘Chess!’

When most of us are feeling weak.

Then after half an hour of Greek

He’d keep them in the chairs they sat in,

Switch their books and yell out, ‘Latin!’

Something told him they would star

In ballet or in opera,

So with the zeal of ancient Sparta

He drilled them for La Traviata.

He’d make them play the violin

Then tell them with a sickly grin,

Containing just a hint of menace,

‘February’s great for tennis.

Come and meet your tennis teacher.

Come on, kids, say pleased to meet ya!’

Poor Jim and Molly did their best,

And yet they knew the vital test

For dad, more vital than a course

In how to serve or ride a horse,

Was quenching his hormonal need

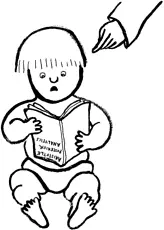

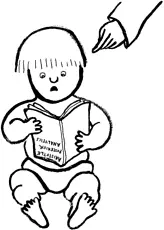

To watch his little children READ.

The surest way of pleasing him

Was sitting like two cherubim

In silence and for simply ages

Rustling slowly through the pages.

Until he’d spot them, stop, and look,

And gasp, ‘My word – they’ve got a book!’

He’d hide behind the door to spy.

A tear would glisten in each eye.

He’d hug himself. He’d cut a caper:

‘They’re reading printed words on paper!’

So how do you think his children could

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Читать дальше

![Джеффри Арчер - The Short, the Long and the Tall [С иллюстрациями]](/books/388600/dzheffri-archer-the-short-the-long-and-the-tall-s-thumb.webp)