Moreover, as Professor Landes has observed, this unprecedented increase in man’s productivity was self-sustaining:

Where previously an amelioration of the conditions of existence, hence of survival, and an increase in economic opportunity had always been followed by a rise in population that eventually consumed the gains achieved, now for the first time in history, both the economy and the knowledge were growing fast enough to generate a continuing flow of investment and technological innovation, a flow that lifted beyond visible limits the ceiling of Malthus’s positive checks. 4

The latter remark is also vitally important. From the eighteenth century onward, the growth in world population had begun to accelerate: Europe’s numbers rose from 140 million in 1750 to 187 million in 1800 to 266 million in 1850; Asia’s exploded from over 400 million in 1750 to around 700 million a century later. 5 Whatever the reasons – better climatic conditions, improved fecundity, decline in diseases – increases of that size were alarming; and although agricultural output both in Europe and Asia also expanded in the eighteenth century and was in fact another general reason for the rise in population, the sheer number of new heads (and stomachs) threatened over time to cancel out the benefits of all such additions in agricultural output. Pressure upon marginal lands, rural unemployment, and a vast drift of families into the already overcrowded cities of Europe in the late eighteenth century were but some of the symptoms of this population surge. 6

What the Industrial Revolution in Britain did (in very crude macroeconomic terms) was to so increase productivity on a sustained basis that the consequent expansion both in national wealth and in the population’s purchasing power constantly outweighed the rise in numbers. While the country’s population rose from 10.5 million in 1801 to 41.8 million in 1911 – an annual increase of 1.26 per cent – its national product rose much faster, perhaps as much as fourteenfold over the nineteenth century. Depending upon the area covered by the statistics, *there was an annual average rise in gross national product of between 2 and 2.25 per cent. In Queen Victoria’s reign alone, product per capita rose two and a half times.

Compared with the growth rates achieved by many nations after 1945, these were not spectacular figures. It was also true, as social historians remind us, that the Industrial Revolution inflicted awful costs upon the new proletariat which laboured in the factories and mines and lived in the unhealthy, crowded, jerry-built cities. Yet the fundamental point remains that the sustained increases in productivity of the Machine Age brought widespread benefits over time: average real wages in Britain rose between 15 and 25 per cent in the years 1815–50, and by an impressive 80 per cent in the next half-century. ‘The central problem of the age’, Ashton has reminded those critics who believe that industrialization was a disaster, ‘was how to feed and clothe and employ generations of children outnumbering by far those of any earlier time.’ 7 The new machines not only employed an increasingly large share of the burgeoning population, but also boosted the nation’s overall per capita income; and the rising demand of urban workers for foodstuffs and essential goods was soon to be met by a steam-driven communications revolution, with railways and steamships bringing the agricultural surpluses of the New World to satisfy the requirements of the Old.

We can grasp this point in a different way by using Professor Landes’s calculations. In 1870, he notes, the United Kingdom was using 100 million tons of coal, which was ‘equivalent to 800 million million Calories of energy, enough to feed a population of 850 million adult males for a year (actual population was then about 31 million)’. Again, the capacity of Britain’s steam engines in 1870, some 4 million horsepower, was equivalent to the power which could be generated by 40 million men; but ‘this many men would have eaten some 320 million bushels of wheat a year – more than three times the annual output of the entire United Kingdom in 1867–71’. 8 The use of inanimate sources of power allowed industrial man to transcend the limitations of biology and to create spectacular increases in production and wealth without succumbing to the weight of a fast-growing population. By contrast, Ashton soberly noted (as late as 1947):

There are today on the plains of India and China men and women, plague-ridden and hungry, living lives little better, to outward appearance, than those of the cattle that toil with them by day and share their places of sleep by night. Such Asiatic standards, and such unmechanized horrors, are the lot of those who increase their numbers without passing through an industrial revolution. 9

The Eclipse of the Non-European World

Before discussing the effects of the Industrial Revolution upon the Great Power system, it will be as well to understand its impact farther afield, especially upon China, India, and other non-European societies. The losses they suffered were twofold, both relative and absolute. It was not the case, as was once fancied, that the peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America lived a happy, ideal existence prior to the impact of western man. ‘The elemental truth must be stressed that the characteristic of any country before its industrial revolution and modernization is poverty … with low productivity, low output per head, in traditional agriculture, any economy which has agriculture as the main constituent of its national income does not produce much of a surplus above the immediate requirements of consumption …’ 10 On the other hand, in view of the fact that in 1800 agricultural production formed the basis of both European and non-European societies, and of the further fact that in countries such as India and China there also existed many traders, textile producers, and craftsmen, the differences in per capita income were not enormous; an Indian handloom weaver, for example, may have earned perhaps as much as half of his European equivalent prior to industrialization. What this also meant was that, given the sheer numbers of Asiatic peasants and craftsmen, Asia still contained a far larger share of world manufacturing output *than did the much less populous Europe before the steam engine and the power loom transformed the world’s balances.

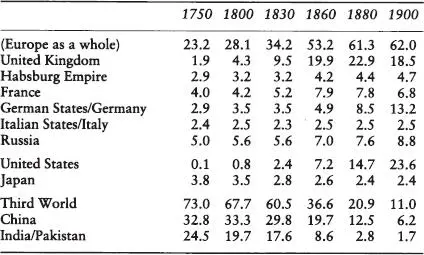

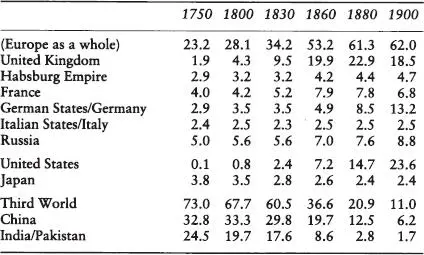

Just how dramatically those balances shifted in consequence of European industrialization and expansion can be seen in Bairoch’s two ingenious calculations (see Tables 6– 7). 11

TABLE 6. Relative Shares of World Manufacturing Output, 1750–1900

TABLE 7. Per Capita Levels of Industrialization, 1750–1900

(relative to UK in 1900 = 100)

The root cause of these transformations, it is clear, lay in the staggering increases in productivity emanating from the Industrial Revolution. Between, say, the 1750s and the 1830s the mechanization of spinning in Britain had increased productivity in that sector alone by a factor of 300 to 400, so it is not surprising that the British share of total world manufacturing rose dramatically – and continued to rise as it turned itself into the ‘first industrial nation’. 12 When other European states and the United States followed the path to industrialization, their shares also rose steadily, as did their per capita levels of industrialization and their national wealth. But the story for China and India was quite a different one. Not only did their shares of total world manufacturing shrink relatively, simply because the West’s output was rising so swiftly; but in some cases their economies declined absolutely, that is, they de -industrialized, because of the penetration of their traditional markets by the far cheaper and better products of the Lancashire textile factories. After 1813 (when the East India Company’s trade monopoly ended), imports of cotton fabrics into India rose spectacularly, from 1 million yards (1814) to 51 million (1830) to 995 million (1870), driving out many of the traditional domestic producers in the process. Finally – and this returns us to Ashton’s point about the grinding poverty of ‘those who increase their numbers without passing through an industrial revolution’ – the large rise in the populations of China, India, and other Third World countries probably reduced their general per capita income from one generation to the next. Hence Bairoch’s remarkable – and horrifying – suggestion that whereas the per capita levels of industrialization in Europe and the Third World may have been not too far apart from each other in 1750, the latter’s was only one-eighteenth of the former’s (2 per cent to 35 per cent) by 1900, and only one-fiftieth of the United Kingdom’s (2 per cent to 100 per cent).

Читать дальше