What made this inadequacy absolutely certain was the retrograde economic measures attending the exploitation of the Castilian taxpayers. 48 The social ethos of the kingdom had never been very encouraging to trade, but in the early sixteenth century the country was relatively prosperous, boasting a growing population and some significant industries. However, the coming of the Counter-Reformation and of the Habsburgs’ many wars stimulated the religious and military elements in Spanish society while weakening the commercial ones. The economic incentives which existed in this society all suggested the wisdom of acquiring a church benefice or purchasing a patent of minor nobility. There was a chronic lack of skilled craftsmen – for example, in the armaments industry – and mobility of labour and flexibility of practice were obstructed by the guilds. 49 Even the development of agriculture was retarded by the privileges of the Mesta, the famous guild of sheep owners whose stock were permitted to graze widely over the kingdom; with Spain’s population growing in the first half of the sixteenth century, this simply led to an increasing need for imports of grain. Since the Mesta’s payments for these grazing rights went into the royal treasury, and a revocation of this practice would have enraged some of the crown’s strongest supporters, there was no prospect of amending the system. Finally, although there were some notable exceptions – the merchants involved in the wool trade, the financier Simon Ruiz, the region around Seville – the Castilian economy on the whole was also heavily dependent upon imports of foreign manufactures and upon the services provided by non-Spaniards, in particular Genoese, Portuguese, and Flemish entrepreneurs. It was dependent, too, upon the Dutch, even during hostilities; ‘by 1640 three-quarters of the goods in Spanish ports were delivered in Dutch ships’, 50 to the profit of the nation’s greatest foes. Not surprisingly, Spain suffered from a constant trade imbalance, which could be made good only by the re-export of American gold and silver.

The horrendous costs of 140 years of war were, therefore, imposed upon a society which was economically ill-equipped to carry them. Unable to raise revenues by the most efficacious means, Habsburg monarchs resorted to a variety of expedients, easy in the short term but disastrous for the long-term good of the country. Taxes were steadily increased by all manner of means, but rarely fell upon the shoulders of those who could bear them most easily, and always tended to hurt commerce. Various privileges, monopolies, and honours were sold off by a government desperate for ready cash. A crude form of deficit financing was evolved, in part by borrowing heavily from the bankers on the credit of future Castilian taxes or American treasure, in part by selling interest-bearing government bonds ( juros ), which in turn drew in funds that might otherwise have been invested in trade and industry. But the government’s debt policy was always done in a hand-to-mouth fashion, without regard for prudent limitations and without the control which a central bank arguably might have imposed. Even by the later stages of Charles V’s reign, therefore, government revenues had been mortgaged for years in advance; in 1543, 65 per cent of ordinary revenue had to be spent paying interest on the juros already issued. The more the crown’s ‘ordinary’ income became alienated, the more desperate was its search for extraordinary revenues and new taxes. The silver coinage, for example, was repeatedly debased with copper vellon . On occasions, the government simply seized incoming American silver destined for private individuals and forced the latter to accept juros in compensation; on other occasions, as has been mentioned above, Spanish kings suspended interest repayments and declared themselves temporarily bankrupt. If this latter action did not always ruin the financial houses themselves, it certainly reduced Madrid’s credit rating for the future.

Even if some of the blows which buffeted the Castilian economy in these years were not man-made, their impact was the greater because of human folly. The plagues which depopulated much of the countryside around the beginning of the seventeenth century were unpredictable, but they added to the other causes – extortionate rents, the actions of the Mesta, military service – which were already hurting agriculture. The flow of American silver was bound to cause economic problems (especially price inflation) which no society of the time had the experience to handle, but the conditions prevailing in Spain meant that this phenomenon hurt the productive classes more than the unproductive, that the silver tended to flow swiftly out of Seville into the hands of foreign bankers and military provision merchants, and that these new transatlantic sources of wealth were exploited by the crown in a way which worked against rather than for the creation of ‘sound finance’. The flood of precious metals from the Indies, it was said, was to Spain as water on a roof – it poured on and then was drained away.

At the centre of the Spanish decline, therefore, was the failure to recognize the importance of preserving the economic underpinnings of a powerful military machine. Time and again the wrong measures were adopted. The expulsion of the Jews, and later the Moriscos; the closing of contacts with foreign universities; the government directive that the Biscayan shipyards should concentrate upon larger warships to the near exclusion of smaller, more useful trading vessels; the sale of monopolies which restricted trade; the heavy taxes upon wool exports, which made them uncompetitive in foreign markets; the internal customs barriers between the various Spanish kingdoms, which hurt commerce and drove up prices – these were just some of the ill-considered decisions which, in the long term, seriously affected Spain’s capacity to carry out the great military role which it had allocated to itself in European (and extra-European) affairs. Although the decline of Spanish power did not fully reveal itself until the 1640s, the causes had existed for decades beforehand.

International Comparisons

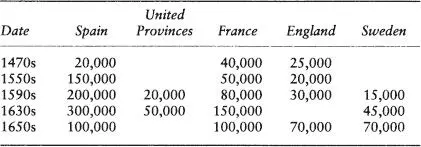

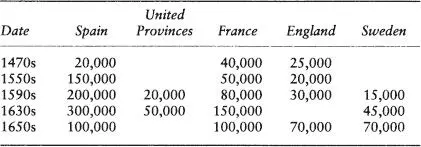

Yet this Habsburg failure, it is important to emphasize, was a relative one. To abandon the story here without examination of the experiences of the other European powers would leave an incomplete analysis. War, as one historian has argued, ‘was by far the severest test that faced the sixteenth-century state’. 51 The changes in military techniques which permitted the great rise in the size of armies and the almost simultaneous evolution of large-scale naval conflict placed enormous new pressures upon the organized societies of the West. Each belligerent had to learn how to create a satisfactory administrative structure to meet the ‘military revolution’; and, of equal importance, it also had to devise new means of paying for the spiralling costs of war. The strains which were placed upon the Habsburg rulers and their subjects may, because of the sheer number of years in which their armies were fighting, have been unusual; but, as Table 1shows, the challenge of supervising and financing bigger military forces was common to all states, many of which seemed to possess far fewer resources than did imperial Spain. How did they meet the test?

TABLE 1. Increase in Military Manpower, 1470–1660 52

Omitted from this brief survey is one of the most persistent and threatening foes of the Habsburgs, the Ottoman Empire, chiefly because its strengths and weaknesses were discussed in the previous chapter; but it is worth recalling that many of the problems and deficiencies with which Turkish administrators had to contend – strategical overextension, failure to tap resources efficiently, the crushing of commercial entrepreneurship in the cause of religious orthodoxy or military prestige – appear similar to those which troubled Philip II and his successors. Also omitted will be Russia and Prussia, as nations whose period as great powers in European politics had not yet arrived; and, further, Poland-Lithuania, which despite its territorial extent was too hampered by ethnic diversity and the fetters of feudalism (serfdom, a backward economy, an elective monarchy, ‘an aristocratic anarchy which was to make it a byword for political ineptitude’ 53 ) to commence its own takeoff to becoming a modern nation-state. Instead, the countries to be examined are the ‘new monarchies’ of France, England, and Sweden and the ‘bourgeois republic’ of the United Provinces.

Читать дальше