William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2015

First published in Great Britain as Went the Day Well? Witnessing Waterloo by William Collins in 2015

Copyright © David Crane 2015

David Crane asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

Cover image: Studies of Royal Horse Artillery Uniform, and of an A.D.C. to the Commander in Chief: a study for ‘The Battle of Waterloo’ (oil on board) by Jones, George (1786–1869), Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, USA/Bridgeman Images.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007358366

Ebook Edition © January 2015 ISBN: 9780007358373

Version: 2015-11-27

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

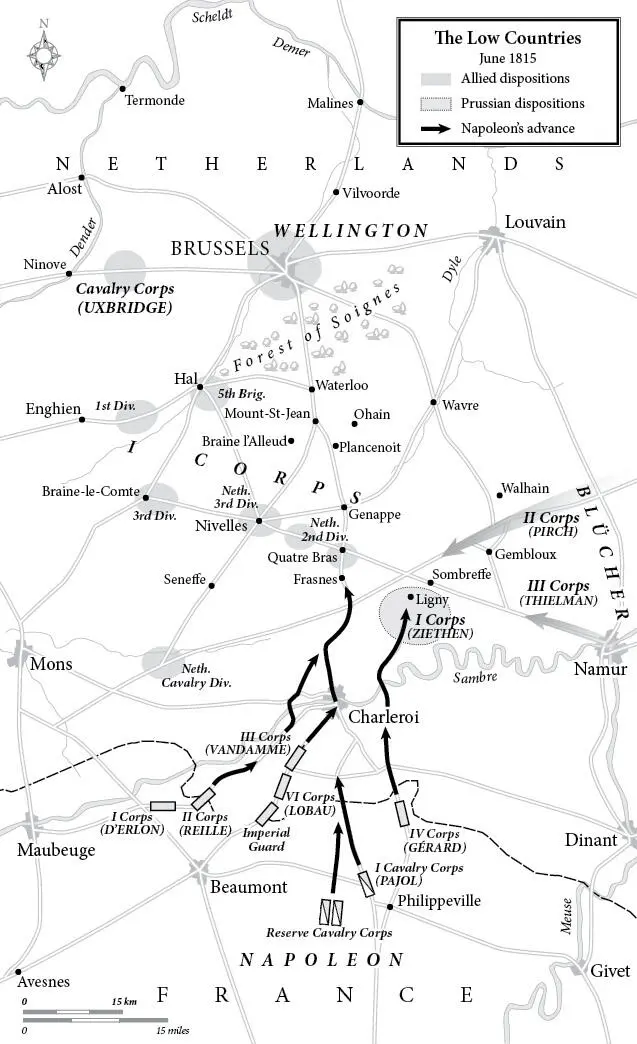

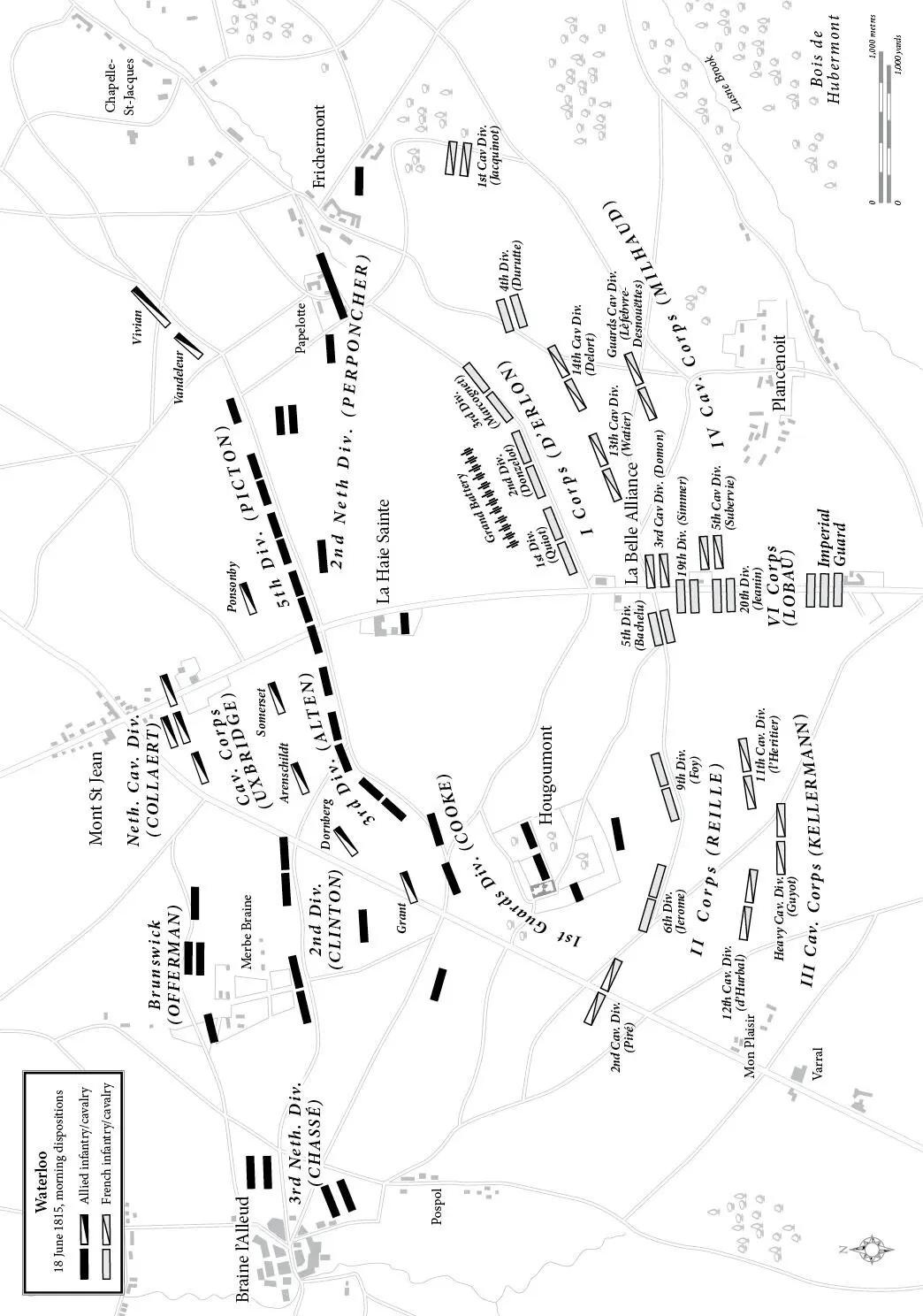

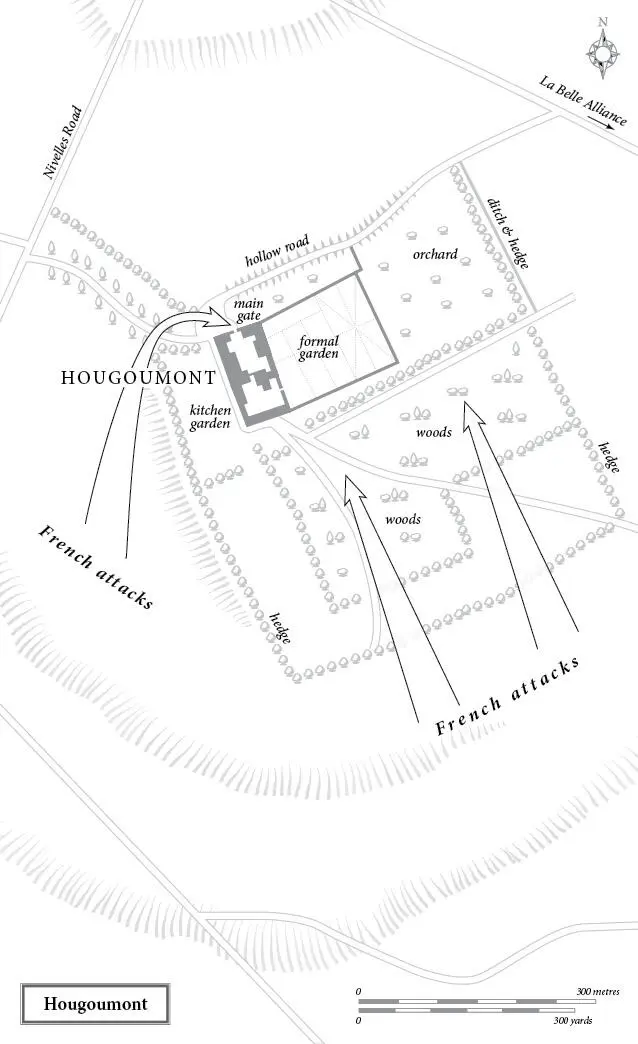

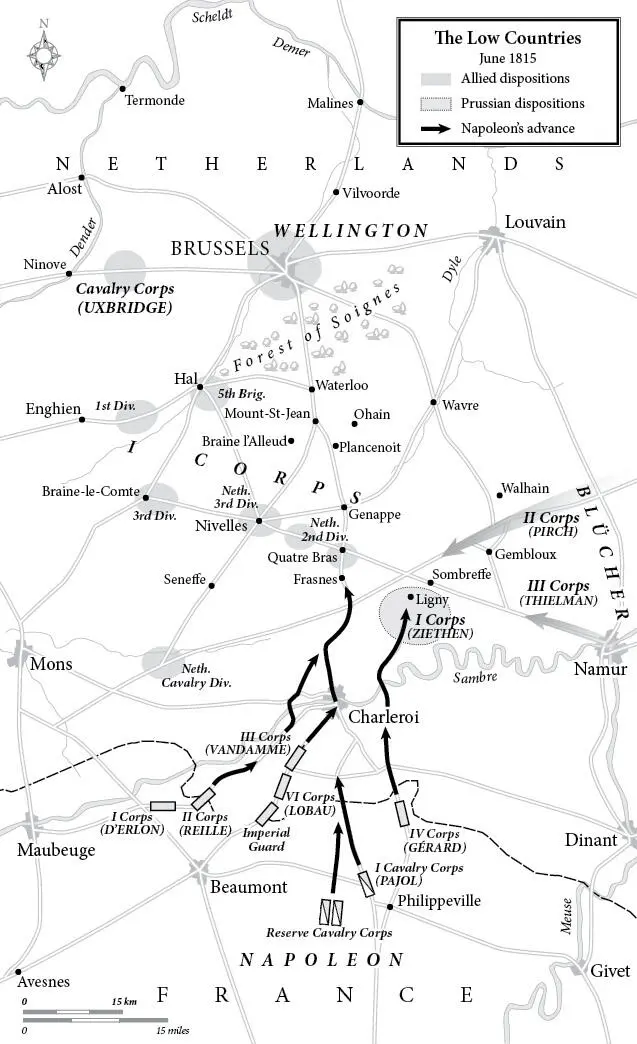

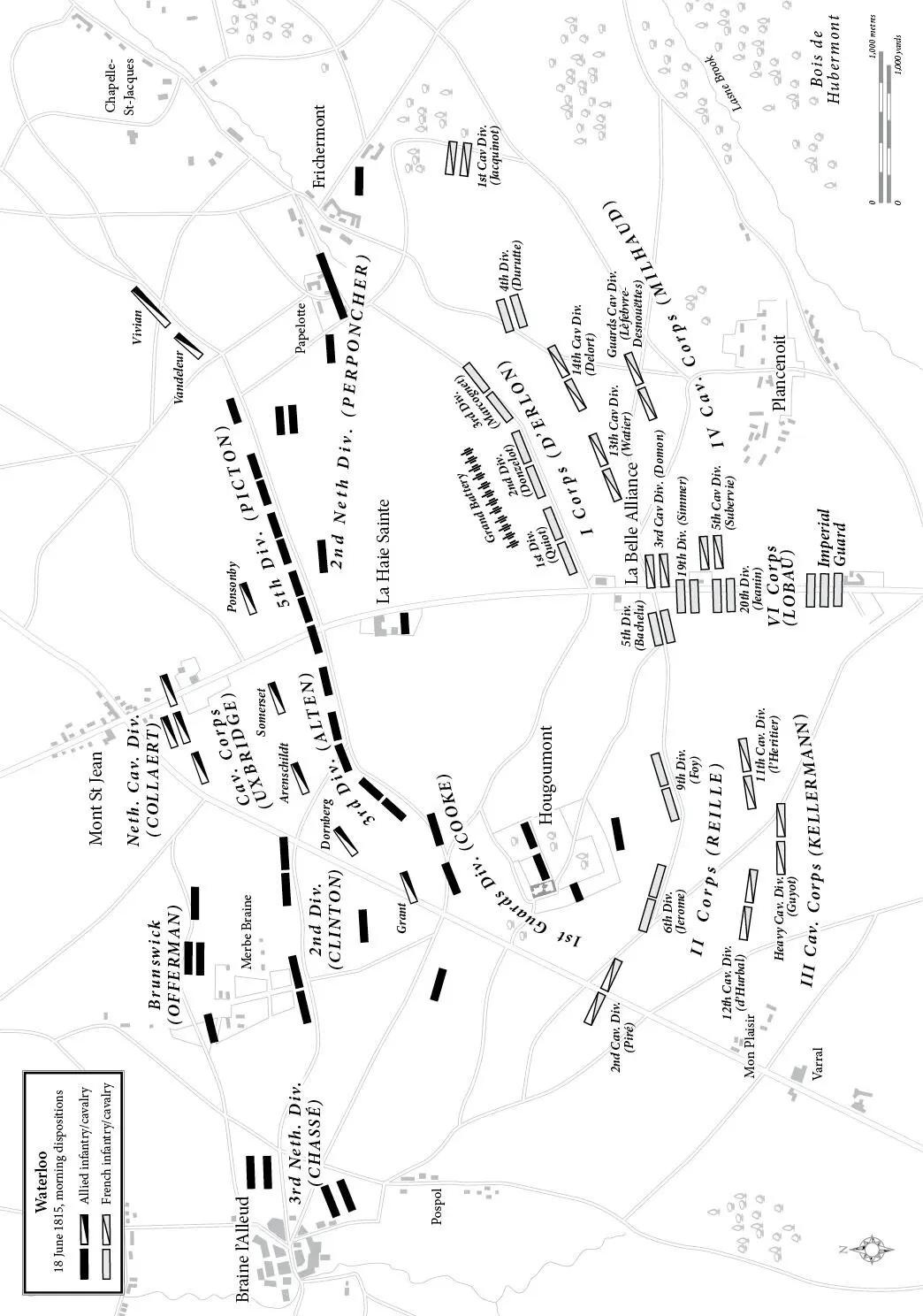

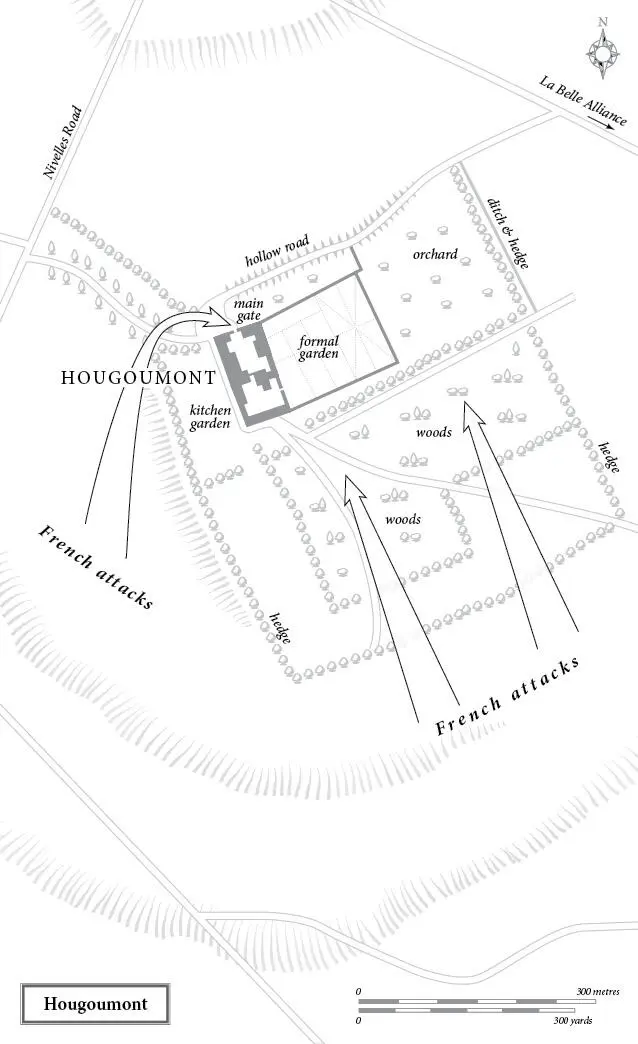

Maps

Prologue

PART I

The Tiger is Out

Midnight: Belgium

1 a.m.: Cut

2 a.m.: Dance of Death

3 a.m.: A Dying World

4 a.m.: I Wish It Was Fit

5 a.m.: A Trellis of Roses

6 a.m.: The Billy Ruffian

7 a.m.: Le Loup de Mer

8 a.m.: The ‘Article’

9 a.m.: Carrot and Stick

10 a.m.: The Sinews of War

11 a.m.: The Sabbath

12 noon: Ah, You Don’t Know Macdonell

1 p.m.: Never Such a Period as This

2 p.m.: Ha, Ha

3 p.m.: The Walking Dead

4 p.m.: The Finger of Providence

5 p.m.: Portraits, Portraits, Portraits

6 p.m.: Vorwärts

7 p.m.: Noblesse Oblige

8 p.m.: A Mild Contusion

9 p.m.: Religionis Causa

10 p.m.: Clay Men

11 p.m.: Went the Day Well?

PART II

The Opening of the Vials

The Days That Are Gone

New Battle Lines

Myth Triumphant

Notes on the Text

Reference Notes

Select Bibliography

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgements

Picture Section

Index

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

Went the day well?

We died and never knew.

But, well or ill,

Freedom, we died for you.

John Maxwell Edmonds

‘There exists a highly respectable school of liberal thought which does not deplore Waterloo. We are not of their number. To us Waterloo is the date of the confounding of liberty.’

Victor Hugo, Les Misérables

On any Sunday or holiday around the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the naval pensioners of Greenwich Hospital, dressed in their tricorn hats and blue uniforms, could be found under a tree near the Observatory in the Park, their telescopes set up, their old yarns of Trafalgar and the Nile primed for retelling, waiting for trade. From the summit of the hill on which they stood the view stretched northwards over the marshes towards Barking church and Epping Forest, and westwards across a forest of masts and docks to the London of Wren, St Paul’s and Westminster Abbey.

It was a sight to make a foreigner quail at the trading might of a modern Tyre – there might be more than two thousand ships lying in the Thames at any one time – but for the Sunday holiday-makers who had made their way up Observatory Hill there was a more macabre demonstration of Britain’s naval power. For the last four hundred years crimes at sea had been punished with all the symbolic pomp the Admiralty could manage at Wapping’s Execution Dock, and for the price of a penny, the pensioners’ customers could hire a telescope and take their fill of the latest victims of naval justice, their bodies tarred and chained, and hanging in iron cages from a gibbet at the river’s edge as a warning against piracy.

On one such holiday in the early summer, while the hawthorn was still out and the great elms and chestnuts of Greenwich Park were looking their best, the humorist and poet Thomas Hood had paid his penny to see the sights and was sitting beneath the trees near the Observatory, watching the early-comers queue to take their turn. In almost every instance the first thing they asked to see were the ‘men in chains’ across the river on the Isle of Dogs, but there was one exception – a young woman he had watched climbing the hill on the arm of her husband, a swarthy-looking able-bodied seaman ‘with a new hat on his Saracen-looking head, a handkerchief full of apples in his left hand, with a bottle neck sticking out of his jacket for a nosegay’ – and it was this pair who caught Hood’s attention.

When it came to their turn, the sailor asked one of the ‘telescope-keepers’ to point out the men in chains for his ‘good lady’, but she told him that ‘she wanted to see something else first’.

‘Well!’ he wanted to know. ‘What is it you’d like better, you fool you?’

‘Why. I wants to see our house in the court, with the flowerpots, and if I don’t see that I won’t see nothing. What’s the men in chains to that ? Give us an apple.’ There was nothing he could say that was going to change her mind, and while he consoled himself with his bottle she took an apple out of the bundle and told the pensioner to turn the telescope towards Limehouse church.

‘Here, Jack! Here it is, pots and all!’ she suddenly screamed. ‘And that’s our bedpost. I left the window up o’purpose as I might see it.’

Jack himself took an observation. ‘D’you see it, Jack?’

‘Yes.’

‘D’ye see the pots?’

‘Yes.’

‘And the bedpost?’

‘Ay, and here Sal, here, here’s the cat looking out of the window.’

‘Come away, let’s look again.’ And then she looked, and squalled, ‘Lord! What a sweet place it is!’ And then she assented to seeing the men in chains, giving Jack the first look.

Anyone familiar with Bruegel’s painting of the Fall of Icarus, with the labourers in the foreground pressing on with the ploughing, unconscious or utterly indifferent to the drama unfolding behind them, will hardly need the reminder but Thomas Hood’s Sal is still a useful warning about the way we see history. For all those nineteenth-century Britons who grew up with the memory of Waterloo, 18 June 1815 could only mean one thing, and yet for the men and women who lived through that day, carrying on their ordinary Sunday lives, going to Greenwich Park or church, oblivious to the fact that on the other side of the Channel the greatest single act of Sabbath breaking in British history was unfolding, it was a different story.

Читать дальше