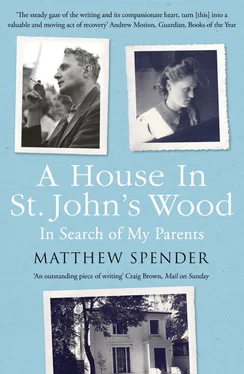

‘For one translucent instant of purely sincere feeling, he hated the children.’ Well, one could reverse this thought. In the upset following his mother’s death, one of Harold’s sons hated his father.

By the time they caught up with each other at Oxford, Wystan was a young intellectual of astonishing self-assurance and Stephen was a tall clumsy well-meaning puppy who couldn’t enter a room without tripping over the carpet. From the moment they met, Wystan treated Stephen like a younger brother, partly because he knew everything about the Spender family. He could see that Stephen’s woolly-mindedness was a disguise, a reaction against his elder brother Michael’s super-efficiency. In his wilful way, Wystan deduced that Stephen was the opposite of what he seemed. Auden believed that the characteristics his friends presented to the world were shields protecting qualities that were their opposites. Thus Stephen wasn’t the hapless weakling that his persona projected. On the contrary, he was as tough as nails.

When they met, Stephen was in love with a young man whom he calls Marston in a series of poems he was writing about him. He’d slip these under the door of Auden’s rooms at Christ Church as soon as they were fit to be read. My father at that time gave his poems to anyone who showed an interest, and he’d already acquired a reputation by the end of his first year at Oxford.

One day in 1929, a few days after he’d left with Auden a new poem and a diary entry about walking along the banks of the River Wye with Marston, Stephen received back a short note in Auden’s almost illegible minuscule. ‘Have read your diary & poems. Am just recovering from the dizzy shock. Come out all day Thursday. Shall order a hamper of cold lunch.’

On the Thursday, they set off by bus from Oxford in the direction of the Berkshire Downs. The bus let them off in the countryside. They clambered through a hedge, hopped over a little ditch and climbed to the top of the nearest hill. They ate egg sandwiches and cold roast chicken and drank a bottle of wine, looking out towards the West Country, which Stephen loved.

Auden said that the great strength of Stephen’s writing was his capacity to describe whatever happened to him ‘as though it had never happened to anyone before’. It was this quality that had made him dizzy. ‘When you create your experience you are excellent. When you attempt to describe or draw attention to your feelings you are rotten.’ He quoted from memory two lines from one of the Marston poems. ‘Taking your wrists and feeling your lips warm’, he said, was excellent. But ‘Let us break our hearts not casually, but on a stated day,’ was bad, because the reader couldn’t believe that the writer’s heart was indeed breaking. On the contrary, it was clear from the poem that the writer was enjoying himself.

Auden said he was jealous of the Marston poems, but he added a word of caution: ‘I console myself by thinking that you are hopelessly literal-minded. Actuality obsesses you so much that you will never be able to free yourself and create a work of pure imagination.’

For the first time, Stephen had been given a new idea about how he could use the material that the world threw at him.

Until now, writing for him had been a kind of lottery. If he was emotionally stirred he wrote down the first words that came into his mind, clinging the while precariously to rhyme and form as a rider clings to a horse which is running away from him: then he hoped one day that such ‘inspiration’ and shots in the dark would produce a successful poem. What had happened now was that an experience had brought him in touch with more than an emotion – with a subject matter capable of crystallization in words.

To be a poet was not the same thing, he now understood, as writing good poems one after the other. There had to be a field of experience out there, a known territory, a vision. Violet had bound Wordsworth to a specific piece of land. Auden mapped out for Stephen poetry as a continent.

During that summer vacation, Stephen bought a little printing press, and in the basement of the family house in Hampstead he set up a group of Auden’s poems. These were the first poems of Auden’s to appear in print, a booklet of ‘About 45 copies’, as the title page casually puts it.

Auden visited the Spender household while this was going on. He asked to be included in the domestic arrangements; meaning a cup of tea for him too, please, whenever the servants made theirs (which was eight times a day).

Wystan told Stephen’s governess – she’d become an important figure in the orphaned phase of his childhood – that Stephen’s ‘innocence’ was, of course, the exact opposite of what it pretended to be. Stephen projected an image of himself as someone who was timid, considerate, over-generous and unsure. This was a result of his refusal to accept himself as he really was: ruthless, selfish and domineering. His generosity was purposefully asphyxiating. He forced people to reject him, so as to avoid the guilt he’d feel if he rejected them. He wrote self-confessional letters to his friends, apparently throwing the whole of his life at the recipient’s head, in order to disguise the fact that he always kept something back. His love for Marston was ‘symptomatic’. Marston had been chosen as a love object because he was untouchable, which of course meant that Stephen himself did not want to be touched.

Stephen’s supposed capacity to be humiliated was a sham. Only love involved humiliation, and Stephen was not prepared to love anyone. ‘One can’t be physically intimate without revealing oneself as one really is.’ In place of intimacy, Stephen cultivated an exaggerated view of his friends. Auden himself was ‘the Sage’. To turn friends into myths was a way of not communicating with them. ‘One does not reveal one’s worse nature to a hero.’

One afternoon during this printing-press phase of their friendship, they went out for a walk on Hampstead Heath. There, Wystan learned that Stephen had no money problems, because he enjoyed an allowance of three hundred pounds a year. What! And yet he complained about being unhappy? Nobody, said Wystan dogmatically, had the right to be unhappy on three hundred pounds a year. He himself would kill for half that amount! In fact, would Stephen consider splitting it? (I can imagine my father laughing politely and changing the subject.)

‘Are you a Verger?’ Wystan asked Stephen abruptly. Stephen said he didn’t understand the question. ‘Are you a Virgin?’ Stephen gave a vague reply. ‘Well, presumably you must know whether you are or you aren’t,’ said Wystan. This particular problem was solved soon afterwards. And when Stephen put up some resistance, Wystan told him briskly, ‘Now, dear, don’t make a fuss.’

AS I SEE it, Auden’s extraordinary matter-of-factness about sex liberated my father, but it was also a challenge. Stephen saw that the guilt that had been drummed into him as a well-brought-up schoolboy could simply be dropped. But if love was to be elevated into an acceptable or even a central part of his life, then with whom and on what terms? This Wystan couldn’t answer – though he said that Marston wasn’t the one. And pragmatic though he may have been in many ways, Auden himself did not solve this problem for a very long time. Christopher found Heinz, Stephen found Tony, but Wystan did not manage to create a permanent love until he found Chester in New York during the Second World War. In 1928, the war was not even remotely visible.

Auden, Isherwood, Spender: these were the three young writers who ‘ganged up and captured the decade’, as Evelyn Waugh put it years later in a grumpy mood. There’s an element of truth in saying that they shared a programme, but as their writings are so different from each other’s, it’s hard to say if this involved life choices, or how life fits into art, or a desire to challenge conventional England, or a need to resist Fascism, or a mixture of all of these.

Читать дальше