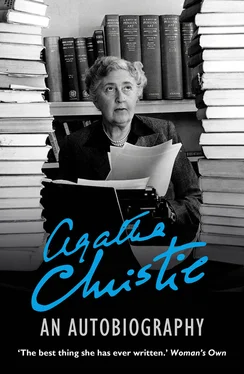

Agatha Christie

An Autobiography

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Collins 1977

Copyright © 1977 Agatha Christie Ltd

Agatha Christie asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

www.agathachristie.com

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780006353287

Ebook Edition OCTOBER 2010 ISBN: 9780007353224

Version: 2017-08-10

Cover

Title Page Agatha Christie An Autobiography

Copyright

Preface

Foreword

Part I Ashfield

Part II ‘Girls and Boys Come out to Play’

Part III Growing up

Part IV Flirting, Courting, Banns Up, Marriage

Part V War

Part VI Round the World

Part VII The Land of Lost Content

Part VIII Second Spring

Part IX Life with Max

Part X The Second War

Part XI Autumn

Epilogue

Keep Reading

Searchable Terms

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

Agatha Christie began to write this book in April 1950; she finished it some fifteen years later when she was 75 years old. Any book written over so long a period must contain certain repetitions and inconsistencies and these have been tidied up. Nothing of importance has been omitted, however: substantially, this is the autobiography as she would have wished it to appear.

She ended it when she was 75 because, as she put it, ‘it seems the right moment to stop. Because, as far as life is concerned, that is all there is to say.’ The last ten years of her life saw some notable triumphs–the film of Murder on the Orient Express; the continued phenomenal run of The Mousetrap; sales of her books throughout the world growing massively year by year and in the United States taking the position at the top of the best-seller charts which had for long been hers as of right in Britain and the Commonwealth; her appointment in 1971 as a Dame of the British Empire. Yet these are no more than extra laurels for achievements that in her own mind were already behind her. In 1965 she could truthfully write…‘I am satisfied. I have done what I want to do.’

Though this is an autobiography, beginning, as autobiographies should, at the beginning and going on to the time she finished writing, Agatha Christie has not allowed herself to be too rigidly circumscribed by the strait-jacket of chronology. Part of the delight of this book lies in the way in which she moves as her fancy takes her; breaking off here to muse on the incomprehensible habits of housemaids or the compensations of old age; jumping forward there because some trait in her childlike character reminds her vividly of her grandson. Nor does she feel any obligation to put everything in. A few episodes which to some might seem important–the celebrated disappearance, for example–are not mentioned, though in that particular case the references elsewhere to an earlier attack of amnesia give the clue to the true course of events. As to the rest, ‘I have remembered, I suppose, what I wanted to remember’, and though she describes her parting from her first husband with moving dignity, what she usually wants to remember are the joyful or the amusing parts of her existence.

Few people can have extracted more intense or more varied fun from life, and this book, above all, is a hymn to the joy of living.

If she had seen this book into print she would undoubtedly have wished to acknowledge many of those who had helped bring that joy into her life; above all, of course, her husband Max and her family. Perhaps it would not be out of place for us, her publishers, to acknowledge her. For fifty years she bullied, berated and delighted us; her insistence on the highest standards in every field of publishing was a constant challenge; her good-humour and zest for life brought warmth into our lives. That she drew great pleasure from her writing is obvious from these pages; what does not appear is the way in which she could communicate that pleasure to all those involved with her work, so that to publish her made business ceaselessly enjoyable. It is certain that both as an author and as a person Agatha Christie will remain unique.

NIMRUD, IRAQ. 2 April 1950.

Nimrud is the modern name of the ancient city of Calah, the military capital of the Assyrians. Our Expedition House is built of mud-brick.

It sprawls out on the east side of the mound, and has a kitchen, a living–and dining-room, a small office, a workroom, a drawing office, a large store and pottery room, and a minute darkroom (we all sleep in tents).

But this year one more room has been added to the Expedition House, a room that measures about three metres square. It has a plastered floor with rush mats and a couple of gay coarse rugs. There is a picture on the wall by a young Iraqi artist, of two donkeys going through the Souk, all done in a maze of brightly coloured cubes. There is a window looking out east towards the snow-topped mountains of Kurdistan. On the outside of the door is affixed a square card on which is printed in cuneiform BEIT AGATHA (Agatha’s House).

So this is my ‘house’ and the idea is that in it I have complete privacy and can apply myself seriously to the business of writing. As the dig proceeds there will probably be no time for this. Objects will need to be cleaned and repaired. There will be photography, labelling, cataloguing and packing. But for the first week or ten days there should be comparative leisure.

It is true that there are certain hindrances to concentration. On the roof overhead, Arab workmen are jumping about, yelling happily to each other and altering the position of insecure ladders. Dogs are barking, turkeys are gobbling. The policeman’s horse is clanking his chain, and the window and door refuse to stay shut, and burst open alternately. I sit at a fairly firm wooden table, and beside me is a gaily painted tin box with which Arabs travel. In it I propose to keep my typescript as it progresses.

I ought to be writing a detective story, but with the writer’s natural urge to write anything but what he should be writing, I long, quite unexpectedly, to write my autobiography. The urge to write one’s autobiography, so I have been told, overtakes everyone sooner or later. It has suddenly overtaken me.

On second thoughts, autobiography is much too grand a word. It suggests a purposeful study of one’s whole life. It implies names, dates and places in tidy chronological order. What I want is to plunge my hand into a lucky dip and come up with a handful of assorted memories.

Читать дальше