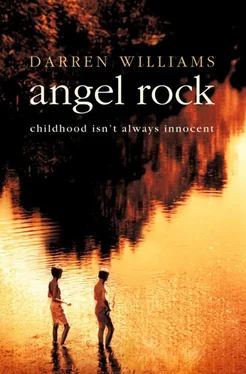

ANGEL ROCK

DARREN WILLIAMS

this one’s for S.A.M .

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

1

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

2

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

3

27

28

29

30

31

32

Acknowledgment

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

1

The first real heat of summer had just steamed into Angel Rock in a welter of frayed tempers and sunburnt noses the afternoon Tom Ferry, almost thirteen years old and still simple-hearted, made his way down to Coop’s Universal from where the school bus had left him. The footpath was baking hot and the grass on either side of it full of bindi-eyes and no easier on his bare feet and his progress was punctuated by spells of hopping to recover from one or the other. When he reached the broad expanse of shade under the hotel verandah he dallied for a minute to let his feet cool down properly. He held up his hand and squinted out at the bright day. Fifty yards away the Universal’s awning gave the last respite before home. Faded signs – a sunset-orange Coke, an airy blue Bushell’s – hung down from it. The sun faded things, it was true, but it also grew them. It was growing him . He could really feel it. He didn’t feel quite like a boy any more – nothing like Flynn – and he liked the sensation; he liked his body growing, the muscles getting bigger on his bones, the ground getting further away.

He licked his lips and set out. Almost immediately the soles of his feet began to burn again. He ran, sucking in warm air through his rounded lips, laughing it out again, lifting his feet, trying to keep them off the concrete for as long as he could. The shop always seemed an age away on days like these, but he finally reached it and then had to stop and bend over and put his hands on his knees for a while to get his breath back. When he had it he went to the big old deepfreeze that sat just inside the shop’s doorway and opened up the lid. Four great half-moons of ice curved out from the sides of the cabinet and he leant over them and plunged his hands and head into the chilled air at its centre. He put his cheek down against the ice and breathed in and felt the cold travel right down into his chest. He laughed at the sensation and waved away the mist with his hands until he could see the box of ice blocks at the bottom of the freezer. He sucked in the sweet, cool smell of them – red ice around ice cream – before reaching down and pulling one out by the tail. He let down the freezer’s lid and then ran to the counter at the back of the shop.

‘Mrs Coop!’ he yelled. ‘Mrs Coop!’

There was no sign of the shopkeeper but in the silence after his yelling he could hear her out the back. The bright light from the open back door reached all the way up the hall and came to rest on the stool sitting in the doorway. She was almost always sitting there whenever Tom came in, fanning herself with a piece of old cardboard. Above her stool, high on the wall, was a dusty bank of brown Bakelite light switches and next to that the electricity meter and the fuse box, and next to that, hanging from a nail, calendar over expired calendar counting back from 1969. Over the counter a sticky mess of old flypaper, bejewelled with blowflies and wasps and beetles, swung gently in the breeze – a grisly record of long-gone summer days. At Tom’s feet, alongside the shelves, were the tracks of countless customers worn into the wood. He followed them while he waited for Mrs Coop to come in, tapping the coin in his hand against the shelves as he went. There was no one else in the shop and the lollies arranged on the counter in coloured boxes seemed to wink at him as he circled. He thought about taking some, gulping them down before Mrs Coop appeared, but his ears immediately began to burn and he had to think about other things to cool them. He closed his eyes and breathed in the smells of the shop. He imagined a calf walking down between the desks at school, collecting books in its dripping mouth, and he imagined his teacher, Mr May, pointing to the blackboard with a fishing rod instead of chalk, and then he saw the smooth neck of the girl who sat in front of him in class and he wondered, for the first time in his life, what a kiss might be like.

When he opened his eyes again the ice block in his hand was already beginning to melt. He was about to shout down the hall again when he heard the shopkeeper coming, saw her swaying from side to side because of her bad hip, heard her wheeze. A blue dress with pale yellow flowers covered her bulk and on her hip, like a freshly picked crop, was the basket full of laundry she’d just collected. The deep black line of her cleavage caught Tom’s eye and held it for a long second.

‘Hello, Mrs Coop,’ he said, lifting his chin.

‘Hello!’ she replied, blinking. ‘Who’s that then?’

‘Tom Ferry.’

‘Ah. Afternoon, Thomas. School’s out then?’

‘Yep.’

‘Plans for the weekend?’

‘Yep.’

‘Good boy! What can I do for you then?’

‘This,’ he said, holding up the ice block by its tip. ‘How much?’

‘Thirty-five cents.’

‘They’ve gone up!’

‘They have?’

Tom looked at the ice block despairingly, then at Mrs Coop. ‘But I haven’t got that much, and I can’t put it back because it’s melting already.’

Mrs Coop laughed at him and then made a waving movement with her hand that set the flesh on her arms wobbling.

‘Well, you’ll just have to owe it to me then,’ she said. ‘Or, better yet, when you’ve finished, you could pull up that grass that’s coming up at the front there and that’ll settle it, I reckon.’

‘You sure?’

‘Yes. Now go on, get stuck into it before it’s just so much coloured water!’

‘All right. Thanks, Mrs Coop. Thanks very much.’

Tom turned to go but then he remembered something. ‘Oh, a pack of Marlboro too, please. For Henry. On his account.’

‘All right then.’

While Mrs Coop reached for the packet Tom stuck his head out of the doorway. There was grass a foot long coming up between the cracks in the concrete out the front of the shop, all the way from where the awning posts met the ground to where the shop and the footpath met.

‘Can I come back and do it tomorrow, Mrs Coop?’ Tom yelled into the shop.

‘Course you can,’ she answered from the gloom. ‘Go on now.’

‘All right. See you tomorrow.’

‘All right. Bye now.’

Tom ran down to where the street ended and the ferry ramp began. He sat down on one of the ramp posts and took a big bite out of the ice block but the cold made his forehead ache almost straight away. When the pain had passed he took smaller bites and caught the melting runoff in the cup of his hand. The ferry was on the far bank and he could see the old ferrymaster sitting in his cabin waiting for cars, the twisting streamers from his pipe vanishing into the breeze. Overhead, fat white clouds clippered across the sky and the wind began to pick up, rippling his shirt, cooling him and the day down. School was over for another week and another Apollo was on its way to the moon and that made even Angel Rock seem a more exciting place. Tomorrow, if it was still hot, he’d take Flynn swimming, or maybe fishing, then later, after dinner, they could lie outside on the grass and try to spot Apollo, or just imagine it soaring out there among the stars.

Читать дальше