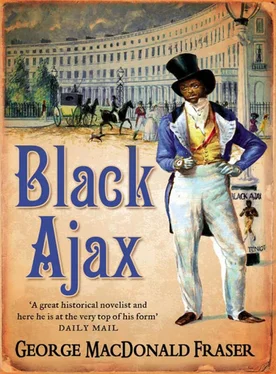

The caped figure striding through the lane of people and carriages held back by the “vinegars”, brisk burly attendants in long coats and top hats carrying horsewhips, his stride becoming a swagger as he shrugs off the cape to reveal the magnificent body beneath, the black skin gleaming as though it has been oiled, the jaunty head with its tight curls, the white silk breeches with ribbons at the knee and coloured scarf encircling the slender waist. He breaks into the shuffle of a plantation dance, laughing and waving to either side, a fine lady smiles from beneath the broad brim of her Mousquetaire and tosses him a posy which he catches, putting a flower behind his ear and bowing low over her hand before dancing on, blowing kisses to the roaring crowd as the faces retreat into shadow and the sound dies …

He is floating high above them, looking down on a vast human amphitheatre, thousands upon cheering thousands ranged about a great roped circle, and beyond them the rolling wooded English countryside is bright in the December noontide, with scattered bands of running people and carts and carriages and horsemen, all hastening to join the huge expectant throng whose every eye is turned on that black and white figure, no bigger than a doll far beneath him, striding ahead, arms raised and hands clasped overhead in the age-old salute of the prize ring. Within the circle he can see the roped square, and the little knots of men standing and crouched about it, the umpires by the scales, the bottle-holders and timekeeper, the vinegars patrolling the space between square and outer circle to ensure order, the gamblers’ runners scurrying to and fro, and at one corner of the square a slim slight man, a Negro like himself but lighter in colour …

… whose eyes are glittering with fierce excitement as they come face to face by the roped square. The mulatto is muttering to him and towelling his shoulders vigorously against the biting cold, but the black fighter does not hear him. As he pulls off his waist-scarf and knots it to the ring-post all his attention is directed to the opposite corner where a man is standing clear of the rest, a tall white man with a rugged open face beneath crisp black curls, clad like himself in breeches and pumps, a man with the shoulders of an Atlas, massive arms crossed on his deep chest, heavy-hipped and long-legged, shifting slightly as he waits, rising on tip-toe and down again. He nods with a little smile, and as the black man raises a hand in reply his other self, back in the Irish barn, feels a strange peace settling upon him, a sense of contentment at the end of a long journey, and he realises with a growing wonder that the journey ended there, by that roped square long ago, when he looked across into the strong acknowledging face of the tall curly-headed man, nodding to him, and recognised, for the first and only time in his life, a companionship that was far beyond any bond of love or affection or loyalty that he had ever known, because it was of equals, apart and alone. He cannot explain it or even understand it, but he knows that the tall man feels it too, and he laughs in pure happiness as he snatches the hat from the top of the ring-post where his scarf is fluttering in the breeze, and sends it skimming over the ropes …

… to fall in the dust of the farmyard, startling a stray fowl which runs squawking wildly, and the red-haired blacksmith is rushing him, blue eyes glaring and arms flailing, and his feet shift and his body sways instinctively as he evades the attack. He knows he is too exhausted, in too much pain, to raise his hands or move his feet, yet somehow his hands are up, his feet are moving, and as the red-haired ruffian turns, the black left fist stabs into his face, and again, and yet again, and that is the last thing he remembers as the shadows close in, and then there is no more memory.

THE WITNESSES

THOMAS (“PADDINGTON”) JONES, retired pugilist and former lightweight champion of England

Who knows what’s inside a black man’s head? Not I, sir, nor you, nor any man. You can’t ever tell. Why? ’Cos they don’t think as we do. They are not of our mind.

Now, I know there’s them as says a white man’s mind is no different, but I hold that it is. Take our own two selves, sir, if you’ll pardon the liberty. You can see the thoughts in my eyes, and – how shall I put it? – yes, you can follow my feelings ’cross this broken old phiz o’ mine, depending as I smile or frown, or set my jaw, or lower my blinds. Is that not so, sir? Course it is. And, begging your pardon, I can do likewise with you, pretty well anyway, though you’re deeper than I am, course you are. Why, this very minute you’re thinking, who’s this cork-brained old clunch with his bust-up map and ears like sponges, to read my mind for me? Yes, you are! No offence, sir, but it’s so, ain’t it? Course it is.

Why’s that, sir? ’Cos we understand each other, though you’re a top-sawyer, as we used to say, and I’m an old bruiser, you’re a learned man and I can barely put my monarch on paper. But we’re white, and English, and of a mind, so to speak. Even with a Frenchman, with his lingo, you can still tell at first glance if he’s glad or blue-devilled or bent on mischief, which he most likely is. It shows, course it does.

Not with your blackamoor, though. Not with the likes o’ big Tom. Oh, he could talk, and make some sense, and do as he was bid (most o’ the time), and put his case – but what was behind them eyes, sir, tell me that? What did he think and feel, down in the marrow of him? You couldn’t tell, sir, you never can, with them –’less they’re dingy Christians (half-white, I mean) like my pal Richmond, and even with him I could never take oath what the black half of his mind was turning over. And I knew him well, nigh on thirty year from when he beat Whipper Green in White Conduit Fields, till he hopped the twig Christmas afore last. Poor old Bill, I fought him twice, and that’s the way to know a man, sir, I tell you. Course it is. I milled him down in forty-one rounds at Brighton, I did, for a fifty-guinea side-stake – we were both lightweights, but he didn’t have my legs (nor my bottom, some said, him being black), and he had this weakness of dropping his left after a feint. Well, what’s your right hand for, eh, when a man leaves the door open thataway? I’d ha’ done him at Hyde Park, and all, but I broke my left famble on his nob, you see, in the eighteenth round – see there, sir, the ring finger’s crooked to this day. If it had been my right, I’d ha’ stood game, held him off and wore him out with a long left, ’cos he didn’t have the legs, as I told you, but when your left won’t fadge, what can you do? Cost my backers a fine roll o’ soft, my having to cry quits …

Beg pardon, sir, where was I? Ah, speaking of knowing Richmond’s mind, as being half-black only. But big Tom, that was black to his backbone – no, a closed book he was. Not so much as a glint of natural feeling, as you might call it, in them strange yellow eyes of his, not even when he looked at you straight, which he seldom did. Head down, as if he was in the sullens, staring at his stampers, hardly a grunt or a mumble, that was his sort, as a rule. You’d as well talk to the parish pump or Turvey’s pig, when the broody fit was on him. You’d wonder if he had a mind at all, or was dicked in the nob.

There were times, mind, when he would break out into the wildest fits, sky-larking and playing the fool like a jobbernowl or a nipper showing off with his antics, and other times, when he got in a proper tweak – in a tweak, sir? Why, bless you, angry, en-raged, in a fair taking – and you’d think, hollo, best stand off and look out, for it’s a wild beast loose. But ’twas no such thing, sir, for all his oaths and roarings, it was only noise, sir, but no action. He knew he was lowly, you see, having been a slave in America, and I reckon that held him in check, somehow, as if he knew ’twasn’t for him to show fight against his betters. Not even in the ring, you say? Ah, that was another piece o’ cheese. He was seldom angry inside the ropes; simple or not, he knew too much for that.

Читать дальше