Dust And Steel

Patrick Mercer

To my wife, Cait

Cover Page

Title Page Dust And Steel Patrick Mercer

Dedication To my wife, Cait

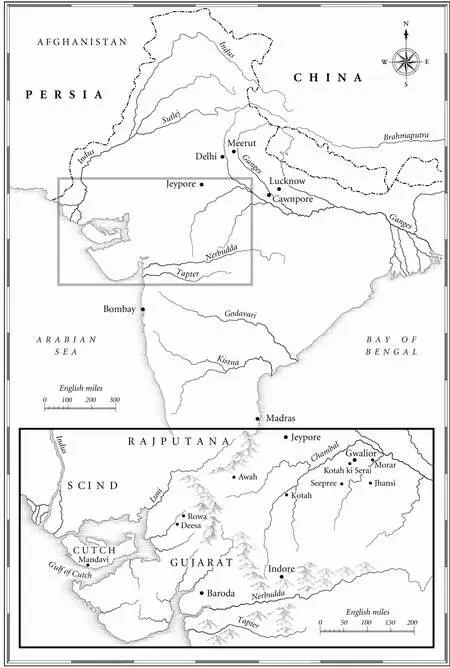

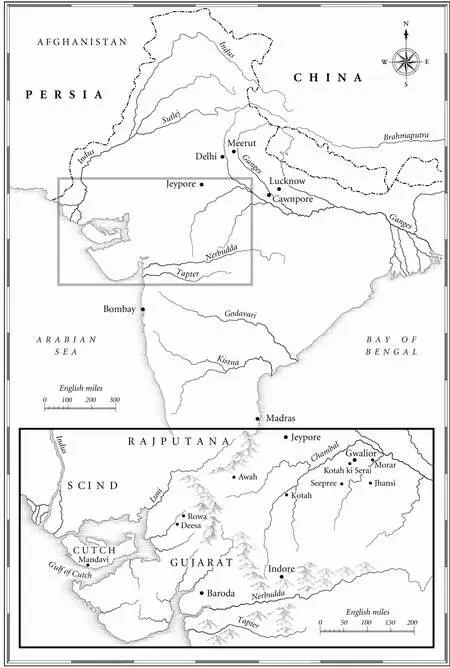

Maps Maps

ONE Bombay

TWO Bombay Brothers

THREE Bombay to Deesa

FOUR The Battle of Rowa

FIVE Clemency

SIX The Relief of Kotah

SEVEN Presentiment

EIGHT Jhansi

NINE Pursuit

TEN Kotah-Ki-Serai

ELEVEN Gwalior

Glossary

Author’s Note

Historical Note

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

‘Get into four ranks, yous.’ Six foot tall and completely poised, McGucken pushed and shoved the first couple of dozen men onto the jetty into a semblance of order. At thirty-two, the Glasgow man looked ten years older. A life spent outdoors had left a wind-tan and myriad wrinkles on his face that his whiskers couldn’t hide, whilst his Crimea medals – both British and Turkish – and the red-and-blue-ribboned Distinguished Conduct Medal spoke of his achievements and depth of experience.

‘They look quite grumpy, don’t they, Colour-Sar’nt?’ Captain Tony Morgan tried to make light of the situation. He, too, looked old for his years. He was shorter and slimmer than McGucken: school, much time in the saddle or chasing game, and Victoria’s enemies had left him with no spare flesh, whilst a Russian blade at Inkermann had given him the slightest of limps. He was twenty-seven and by girls in his native Ireland would be described as a ‘well-made man’, dark blond hair and moustaches bestowing a rakish air that he wished he deserved. On his chest bobbed just the two Crimea campaign medals but a brevet-majority – his reward for the capture of The Quarries outside Sevastopol two years before – was worth almost fifty pounds a year in additional pay.

‘Better load before they push those sailors out the way, don’t you think, Colour-Sar’nt?’ Morgan watched as the mob surged forward. ‘Must be three hundred or more now.’

‘No, sir, them skinny lot’ll do us no harm. They’ve not got a firelock amongst ’em; they’re just piss an’ wind.’ McGucken had been at Morgan’s side through all the torments of the Crimea, watching his officer develop from callow boy from the bogs of Cork into as fine a leader as any he’d served under. Muscovite shells, and endless nights together on windswept hillsides or in water-logged trenches had forged a friendship that would be hard to dent, yet there remained a respectful distance between them. ‘Let’s save our lead for the mutineers. We’ll push this lot aside with butts and the toe of our boots, if needs be.’

Morgan knew McGucken was right, and as the next boatload of men shuffled their way into disciplined ranks, he reached down the ladder towards his commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Hume. He was another old Crimea hand whose promotion and Companion of the Bath had come on the back of the efforts of some of the boys who now jostled in front of him in the heat of the Indian sun.

‘Right, Morgan, as soon as your men are ready, let’s get moving to the fort. The other companies will follow as soon as they’re ashore, but gather these sailors in as we go. They may be useful.’ Hume stood no more than five-foot seven and wore his hair and whiskers long. At thirty-eight, he was young to be in command of an infantry battalion.

Morgan looked quizzically towards the angry crowd.

‘Come on, we’ve got the Honourable East India Company to save. Then you’ll be wanting your dinner, won’t you, Corporal Pegg?’ chaffed Hume.

‘Nice quart o’ beer would suit me, sir,’ replied the chubby corporal. Pegg was twenty, a veteran who had been with the Grenadier Company for his entire service, first as a drummer and now with a chevron on his sleeve.

The piece of sang-froid worked. It was as if the crowd simply wasn’t there. Morgan had seen Hume do this before – he would defuse a crisis with a banality, speaking with an easy confidence that was infectious. Now all uncertainty vanished from the men and at McGucken’s word of command, the ninety-strong scarlet phalanx strode down the jetty and fanned out into column of platoons as they reached the road. As the dust rose from their boots, the crowd melted away in front of them, the cat-calling and jeers dying in the Indians’ throats as the muscle of a battle-ready company of British troops bore down upon them.

‘Morgan, this fellow, Jameson, here, knows the town and the way to the fort.’ Hume had grabbed one of the sailors who, along with the rest of his and two other civilian crews, had been the only armed and disciplined force available to help the slender British garrison of Bombay when the talk of mutiny had started.

‘I do, sir. Commanding officer of the Tenth is waiting for you there.’ Jameson had seen Colonel Brewill of the 10th Bombay Native Infantry just a couple of hours before, when he was sent to guide the new arrivals over the mile and a half from the docks up to the fort. ‘Mr Forgett as well, sir.’

‘Who’s he, Jameson?’ asked Hume.

‘Oh, sorry, sir, he’s the chief o’ police. Rare plucked, he is. Been scuttling about dressed like a native ever since we got ’ere, ’e as, spyin’ on the Pandies at their meetings an’ their secret oath ceremonies.’ The squat sailor’s eyes shone out of his tanned, bearded face. ‘Things was fairly calm till yesterday when he arrested three of the rogues, ’e did, an’ took ’em off to the fort. Then the crowds came out an’ the whole town’s got dead ugly.’

The company tramped on towards the fort, red dust rising in a cloud behind them, their rifles sloped on their right shoulders, left arms swinging across their bodies in an easy rhythm. They were an impressive sight. The Grenadier Company still had the biggest men of the Regiment in their ranks, and at least a third of them had seen fierce fighting before. At the very sight of such men even the parrots fled squawking on green and yellow wings from the thick brush that lined the road into the centre of Bombay.

‘Bugger off, you mangy get.’ Only a pye-dog with a patchy coat had chosen to stay and investigate the marching column, but with a shriek, and its tail curled tightly over its balls, the cur ran off towards a drainage ditch as the toe of Lance-Corporal Pegg’s boot met its rump.

‘Fuckin’ ’orrible, sir. Did you see all them sores on its back?’ Pegg was adept at casual violence, particularly when the recipient posed little threat to himself.

‘I did, Corporal Pegg, but I should save your energies for the mutineers, if I were you.’ Reluctantly, Morgan had grown to value Pegg, for whilst the young non-commissioned officer lacked initiative, he was always to hand in a crisis.

‘’Ave this lot of sepoys gone rotten then, sir, like that lot up by Delhi?’

On board ship news had been scarce. The first mutinies in the Bengal Presidency in Meerut, Delhi, Cawnpore and Lucknow had started in May, rumours of terrible battles and massacres filtering down to the British. Now, a month later, no one was sure whether the native troops across Madras and especially the three sepoy battalions here in Bombay were fully trustworthy or not. So news that the Polmaise had been diverted from her journey to the Cape, with half a battalion of experienced British troops aboard, had been extremely welcome.

‘I don’t know, Corporal Pegg, but we shall find out soon enough, if we can get past those things,’ replied Morgan, as the company approached the arched timber doors of the City Fort, where four camels and their loads of hay were jammed tightly together.

Читать дальше